The Truth About Bloodlines in Horse Racing

A fascinating report courtesy of True.Ink’s campaign to crowdsource a race horse.

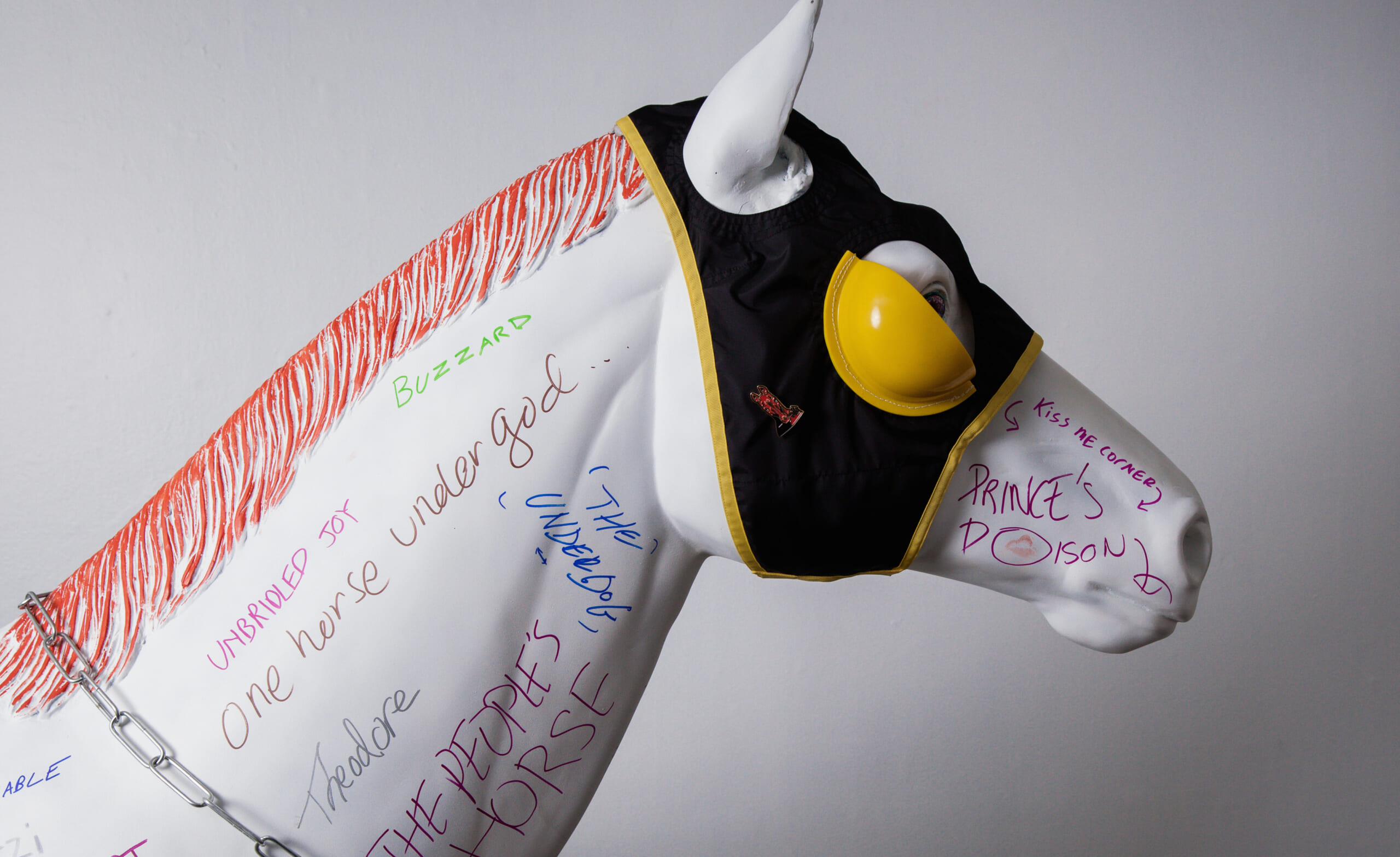

The following story about the power of bloodlines in horse racing comes as part of The People’s Horse, the first-ever campaign to crowdsource a racehorse. It was written by Geoffrey Gray, bestselling author and founder of True.Ink, a new experiential adventure magazine.

The horse auction in Timonium, Maryland, barely draws enough visitors to fill a section of the old state fairgrounds an racing track outside of Baltimore.

Yet the auction last month, amid the faded odds boards for gamblers and across from a sprawling string of strip malls, matches the best racing prospects in the country with owners spending millions. Here in the empty bleachers, the scouts of the racing world—”pinhookers” or “bloodstock agents”, they’re called—make notes in their auction catalogues, crack inside jokes and watch hundreds of horses sprint down the track—known as breezing—with their stopwatches.

It’s a barren scene, but the skill and knowledge behind picking which racehorse to buy (and which to avoid) dates back centuries to the earliest bloodlines. It’s critical for a horse owner to find a scout who can pick a winner.While it’s still early for us to choose The People’s Horse, we went to Timonium to make new friends and learn about this art. Outside of traditional folks who use wisdom culled from growing up on horse farms and watching thousands of races, we met Jeffrey Seder, who picks racehorse with a far different methodology.

https://vimeo.com/168724255″ tml-render-layout=”inline” tml-embed-thumbnail=”https://i.vimeocdn.com/video/573434961_1280.jpg

Seder has had an unorthodox ride into the horse racing game. It began with the American bobsled team during his work for the U.S. Olympic Committee in the late 1970s. Back then, Seder knew little about winter sports, but he was a rising analyst with a mind for collecting and understanding data. After graduating from Harvard with a legal and business degree, Seder used his analytical chops to break down the problem.

“The bobsled team had never been in medal contention,” Seder told us about his days up in Lake Placid. The Swiss and East Germans were winning the lion’s share of the medals, he recalls. U.S. Olympic officials were frustrated they couldn’t compete. What were the Swiss doing that the Americans were not? Seder’s solution was a slow motion camera.

“We filmed them,” he said, “and then we compared what the hell they were doing to what we were doing.”The videotape revealed the Americans’ error.“We were trying to get football players and tremendous athletes to push the sled,” he said. “A big mistake. You didn’t need raw power pushing the sled. You needed ballet dancers.”The problem with pushing the sled hard, the slow motion video tape revealed, was that the brute force created a wobble on the ice and a flaw in technique.

“[The wobble] created friction and made the sled go slower,” Seder said. The brute bobsledders were replaced with graceful ones. Americans started winning bobsled medals, he says, thanks to the intelligence they developed under slow motion camera. Seder was so pleased with the success of the analysis that he decided to start his own company and apply a similar methodology to his true passion: racehorses.When his interest in horses started, Seder was still at Harvard.

He went on a date at a rental stable, fell in love with riding, purchased a horse, and the addiction blossomed. Horses calmed him, as they do many. They gave him a sense of ease and “a connection to something greater, a force that unlike people does not come with the competition, fear or approval desires.

”He read about the origins of horses, and how the modern thoroughbred evolved from merging complimentary bloodlines. During the Crusades, English nobles returned from the Middle East with speedy Arab stallions and bred them with their sturdier horses to birth the modern thoroughbred. And from the inception of the racehorse, the game for horse owners and breeders has been to artfully match mare and stallion to generate winning progeny.

Bloodlines are a lucrative benchmark in the price of a horse. In 2006, for instance, a colt named The Green Monkey was sold at a two-year old auction for $16 million, the highest price ever paid for a racehorse, with a bloodline that ran deep into the shared history of fantastic racehorses and their fantastically wealthy owners.

The price of the Green Monkey was based on his deep bloodline connections to Northern Dancer, the most successful stallion of the 20th century and first to claim a $1 million stud fee. Northern Dancer had been sired by Native Dancer, aka The Grey Ghost, a famous horse raised on the farm of Alfred Vanderbilt Jr., he of the fabulously wealthy railroad family and former owner of the legendary Pimlico Racetrack in Baltimore.

But for all his rich pedigree, the Green Monkey was a flop. He never won a race, and he retired after only three starts.Seder was impressed with the Green Monkey’s speed, but not his technique. He analyzed the horse at auction with his slow motion camera, and could see the issue with his gallop.

“He was in a rotary gallop and couldn’t get out of it,” he said. “It looked dramatic, was fast as hell, but it didn’t mean shit. If he’s not talented enough to change leads and get into a racing gallop, he won’t be able to sustain that kind of pace.

”The inability of young horses to flip from the rotary gallop into a racing gait is among the minute yet leading metrics that Seder and his team at Equine Biomechanics & Exercise Physiology, Inc. have isolated as determining factors of a racehorse’s success. In all of Seder’s research, analyzing tens of thousands of racehorses over the past three decades, he’s concluded the pedigree of a horse is wildly overhyped.

“Breeding is a very weak predictor of how good a horse can be, but it’s a very good predictor of how much the horse will cost,” Seder told us.Despite the controversial idea that bloodlines matter little in horse racing, Seder has ground to stand on. He and his company were behind the success of American Pharaoh, winner of the Triple Crown and the greatest horse in recent memory.

Seder had used his analytic, data-driven approach to purchase American Pharaoh’s mother, Littleprincessemma, and an entire band of brood mares for Ahmed Zayat, the Egyptian-born businessman.In analyzing Littleprincessemma, Seder did not check her bloodline before purchasing her. He obsessed over other details.

“I liked the size and shape of her left ventricle,” he said. “She was well put together. The size of her trachea, her spleen. She had it all!”Thanks to Littleprincessemma and the entire band of mares that Seder was able to assemble, Zayat has emerged in recent years as one of the leading owners in horse racing. In addition to American Pharaoh, Seder’s research is behind the careers of dozens of Stakes winners. Forever Together earned nearly $3 million, Bobbie’s Kitten won the Breeder’s Cup. Madcap Escapade, Prayer for Relief, the list goes on. Before big races, gamblers from around the country regularly seek his data and counsel before placing bets.

In total, discussing the criteria for The People’s Horse, Seder told us he and his team had identified 48 total factors that are dominant in predicting a successful racehorse.“It’s like musical notes of a symphony,” Seder said of the leading criteria he uses to determine a great horse. “If you throw notes together, you’re not going to get a symphony. Same with elite horses. Everything they do is fixed together in a pattern that works, and there’s more than one pattern that works.”

Among the determining criteria, the leading factors have nothing to do with pedigree. The belief in the power of bloodlines, he says, is tangled up in a knot of desire, class, status and pride.“It’s full of fads,” he says, and decisions are based on emotion. “It’s the pride of owning a part of a bloodline, having the chance to say they own it. It’s like saying they own John F. Kennedy’s shoes or Pierre du Pont’s lighter.”The numbers don’t add up for him.

“If you take the very top stallions that get the most expensive stud fees—say, 10% of them do well, and 1-to-2% become champions—than everybody goes bananas,” he says. “Now, consider the cost. You’re paying about $1 million for the mare, a stud fee of $200k for the stallion, and guaranteeing that 90% to 98% of what you’ll get won’t be that good. Now how powerful of a predictor is that?”After years of research, Seder has identified his critical area.

“We immediately found the heart’s really different in the really good racehorses that in the average racehorse, in a lot of ways.”In general, a horse with a bigger heart is more likely to succeed because the heart is stronger and can pump more blood throughout the body.

However, determining the actual size and strength of the heart, measuring the organ and its ability to pump blood during a race has been fraught with challenges.“When we started out, there were transducers and ultrasound machines in big universities, but we needed to go into stalls at race tracks and at barns,” he recalled.The big devices didn’t work, so Seder built his own devices.

“We used parts from an Apple 2C, and stuff from a defense contractor,” he said. “We had to go down around Washington D.C. and get black box stuff, and put it all together. We programmed in machine language to make the goddamn thing work.”Another critical factor involves the horse’s lungs and ease of breathing while racing.“We built a mask to go on the horse, and to get him really working, we put him in a pool in a sling,” Seder said.

“We were going to collect the gases, so that we could do the equivalent of what they were doing with human athletes, and finally got a weather balloon to catch all this gas. It turned out that their lung capacity was immense. It was a thermal regulation thing; it wasn’t just to oxygenate the blood.”The high lung capacity changed their training recommendations.“To try and train their lung capacity, the way that we do for humans, was silly,” he said. “We were creating pulmonary hemorrhages and all kinds of injuries and attitude problems.”

Finally, they developed new machines and techniques to gauge the horse’s breathing, even while they were running on the training track. But perhaps the easiest factors to test and measure were apparent on the slow motion videotape.“Until they get the stress of the exercise, you don’t see whether it’s really going to work in racing or not,” Seder said of a horse’s gait. “A horse may walk fine, he may even slowly cantor fine, but when he gets really rocking and rolling, it may all go to hell.

BANGING HOOVES

In the empty stands at Timonium, Seder and his team had mastered their setup. There were a few cameramen to record the galloping horses in slow motion and a microphone to capture how their hooves sounded on the dirt. Behind the wires and mess of equipment, Seder himself watched each horse frame by frame while making notes and pointing to the monitor to illuminate the flaws in gait.In one horse, he easily saw a common problem.

“Do you see how the hooves hit during the stride?” he said, pointing to the touching of hooves mid-gait. “This horse may be flying in speed, but over the course of his career, knocking those feet together in every gait and every race and every training session, he’s going to have sore feet. And when he walks out to the track to race, those feet will be in pain. It’s a small detail, tiny, but how can anyone expect a horse to win races and have a long career with sore feet?”

BANGING ELBOWS

The hooves were not the only casualties.“See here?” he went on, pausing the video. “This horse is whacking itself in the elbow. See it tuck it behind? It’s twisted when it does that. It comes out and wobbles all over the place, snapping all the joints. These legs are really fragile and there’s a lot of ligaments and tendons, eight bones in the knee and every stride those little bones in there are banging into each other.”

THE ROTARY GALLOP

Outside of contact, he also analyzed the way the legs moved on the track.“This horse is doing what we called a rotary gallop,” he said, describing a shortcoming of The Green Monkey. “The motion is like around the legs of a table in order, in a circle for a rotary gallop. And it’s neither the right lead or the left lead and it makes the stride look longer and smoother, and they use it for sharp acceleration out of the starting gate and they’re not supposed to stay in it.”During a race, the gait of a horse should change.

“With these young horses going this fast, they try to change their leads from right handed to left handed, and they can’t finish it because they’re not experienced or coordinated enough and get stuck in the middle. You can’t do this in a race. You’ll win the first half of the race and then you’ll poop out and drop back, which happens often. Most people won’t catch that.”Another horse came down the stretch. Then another. Then five more. In total, over 600 horses were for sale. Whittling down the lot was Seder’s challenge.“Pedigree has something to do with it,” Seder confessed.

“When we look at horses, there’s a higher concentration of good horses that have the criteria we’re looking for that do come from good parents, like the top draft picks that come out of good schools.”For the traditional take—eyeing a horse’s constitution, their personality, and on—Seder has partnered with Patti Miller, another veteran of the horse industry who was once a jockey and a leading trainer in Delaware. Together, they’ve made a complementary pair, using technology as an “overlay” to help determine what can make a great horse.

“It’s not how fast they go, it’s how they go fast,” Miller says.As good as their approach has been, the data and heart measurements fail to quantify yet another element in a great horse. It’s an element that may be impossible to quantify. It’s a spirit, a desire, a personality, a willingness to compete, qualities that have nothing to do with large left ventricles or a good gait.“You need pedigree,” said Billy Turner, the trainer of Seattle Slew, the Triple Crown winner and who works with Seder and Miller. “You need pedigree because it helps to overcome the flaws in the individual horse, and it helps to answer the question that all great racehorses need to have. How bad do they want it?”