8 Things We Learned Inside Sam Adams’ Top-Secret Test Brewery

Welcome to beer lovers’ paradise.

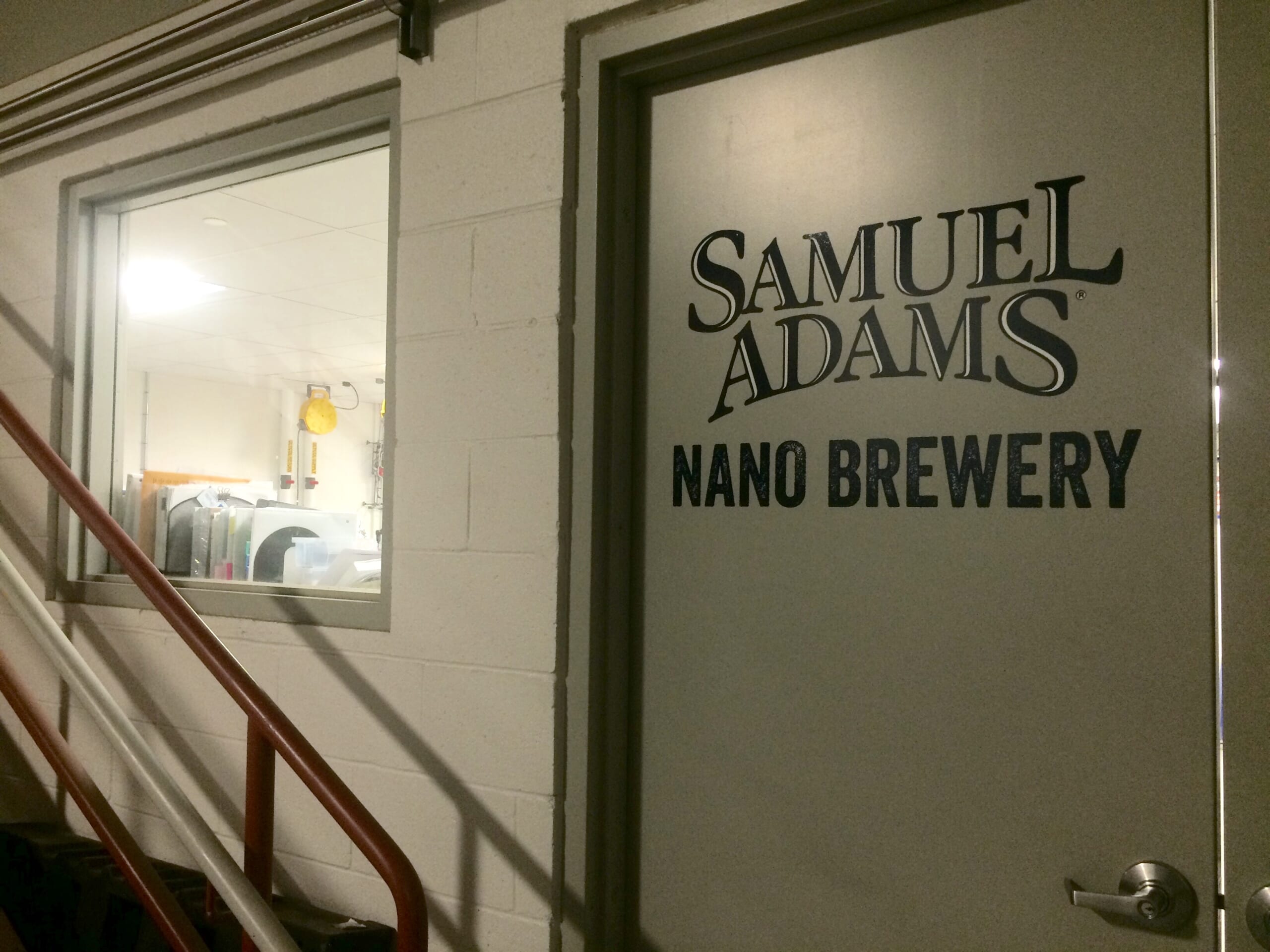

In a small windowless room tucked inside a quaint brick building on the outskirts of Boston exists a facility known as the Nano Brewery. This secret lab is an integral component of the Boston Beer Company’s concentrated effort to keep their family of Samuel Adams beers one step ahead of the competition. It’s also heaven for beer obsessives.

But even if you’re a casual beer drinker, you’ve no doubt noticed there’s an all-out war brewing (sorry) on the shelves of your local bodega. Like the Cola Wars of the ’80s, the Craft Beer Wars have reached a fever pitch. Not only have local breweries been popping up in nooks and crannies all over America, but their wares are displacing the shelf space of oligarchs like Budweiser, Coors, and whatever Miller is calling beer these days.

Despite the homespun-looking labels and cutesy names, however, a lot of these beers aren’t nearly as indie as you might think. Countless breweries have been snatched up by international conglomerates eager to shore up artillery. Favorites like Breckeridge, Goose Island, Revolver, Tarrapin, Lagunitas and Ballast Point have all been absorbed by AB InBev, Molson Coors, Heineken, and others.

Boston Beer Company now stands as the largest American-owned brewery, but as founder Jim Koch is quick to point out, they still only produce 1% of all beer sold in the U.S. That’s why they have to constantly keep innovating, and why we were very happy Koch invited us to check out the Nano Brewery and speak with him and head brewer Megan Parisi about how they’re taking on this insane amount of competition.

1. It’s war, and Sam Adams is once again part of the rebellion.

Sam Adams doesn’t consider the proliferation of craft beers to be their competitor. As far as Koch is considered, he’d be delighted if craft beers took over the entire market. What he sees as competition are Big Beer and their insatiable desire to gobble up once-proud breweries. Hence Koch founded the Brewing the American Dream program in 2008 to help craft brewers gain access to capital and mentoring networks. Let’s have a fair fight, at least.

2. The Nano-Brewery allows brewers to quickly test and refine varietals.

The craft beer land grab finds producers like Boston Beer in a pinch, squeezed by the international big boys on one side and well-funded “craft” beers on the other. To move innovation forward, Koch started the Nano Brewery. The tiny experimental brewery allows BBC brewers to quickly test and refine varietals in a scientific, well-arranged facility.

It was here that Boston Beer recently experimented with dozens of batches to completely reformulate their popular Rebel IPA. To do so, brewers experimented with various hops that were unavailable when Rebel first launched in 2014—including new exclusive proprietary strains—to create a juicier, more tropical citrus flavor.

3. The setup speeds up the development process.

“We’re always working on innovation here,” Parisi tells us as she walks the room. “If there’s a free slot and we have a great idea, we’re gonna try it.”

It’s a tiny room filled with three propane-fired vessels (that produce the wort) and fifteen conical fermenters, each producing 10-gallon batches. In the back of the room 32 draft taps (28 CO2 taps and 4 nitro) are set up to taste the beer.

At any given time, several different beers are being produced and refined. When we visited, a Rebel IPA, Session IPA, Berliner Weisse and Yuzu were all being tested. Each new batch takes about six hours to make, and then it goes into a fermenter for about seven days. After that another week is required for conditioning time.

4. Brewers can fine-tune ingredients here.

“I’ve never had this much ability to dial in a recipe before brewing it and going to market. For me, this is just amazing to really have that chance to break down every ingredient,” explains Parisi. “We’ve figured out all the quirks before we get to our final production; we’re really confident that this is the beer we’re all proud of at its first release.” In other words, no second guessing.

Smaller breweries simply don’t have the time to break down every ingredient, because of economic pressure to get their product out. “It’s something to which we’re completely committed to,” continues Parisi, “just like never releasing anything that isn’t 100% exactly the beer we want it to be.”

5. But the process still takes time.

This is how it’ll start: An idea will come for a beer to fill a certain niche—say, a new citrus fruit-infused beer. They will then look at different flavors and styles to fit that space, and will brew the first recipes here. “Having this small size gives us a ton of flexibility to be able to test all these different, individual varieties,” explains Parisi. “We don’t have to make 10 barrels’ worth of it.”

“This is the first batch of the Yuzu beer, and if it winds up being something we want to pursue, it will probably take a couple months before we feel like it’s ready,” she explains. The process works in two weeks increments until each batch is ready to try, and then there’s another wave of trials. “Usually it’s 4, 5, 7, tries until they send it up to the 10-barrel for production.”

6. You don’t just test new beers—sometimes you test old hops.

But the Nano-Brewery is not just for new product; sometimes it is used to better know ingredients, such as different hops or yeasts. Sure BBC have been around for over three decades, but they still continually run hop trials to figure out how certain strains will work with different types of beers.

“Hops are an agricultural ingredient, they vary from year to year. The processing practices improve. The quality and efficiency in the hops can change, and the variety has just evolved over time, too,” explains Parisi. “You also try to remove expectations just because we’ve tested it before: ‘Oh I know what Cascade tastes like.’ Well, we think we know what Cascade tastes like. What does today’s Cascade taste like?”

Just like a spice in cooking can taste different in a lighter dish, the same hop can taste quite altered in a different beer style. With a Pilsner, for instance, the hop will not taste the same as in an IPA. After a batch is finished, it is then brought to the tasting panel at 10:30 am every day.

7. Sometimes things get heated.

“People get opinionated in the tasting panels, but no one ever yells, ‘You’re wrong!’” Parisi says of the tasting room process. “We need to think about the person who wants to drink this beer. Are they gonna say, ‘This is what I’m looking for.’ It’s certainly never contentious, but sometimes people will differ in their opinions because maybe someone knows the style better.” Ultimately the assembled room has to come to a consensus, whether it’s judging a beer or developing one.

And if it’s a tie? “Well then Jim decides,” says Parisi smiling.

8. Sam Adams can experiment in ways other brewers can’t.

Says Parisi, “I can liken it to my life as a professional musician before this.” (She played clarinet for five years in the US Navy Band.) “This is the practice room; this is where you spend the hours and hours and hours before you ever get onstage for the performance. It’s one night only, you’ve got your concert time, you know exactly what you have to say. That’s what the Nano-Brewery provides: it gives you the confidence that when you get to a finished beer, that’s the concert you wanted to give.”

“And it’s not just about the resources,” she says after a short pause. “It’s about having the commitment to allocating those resources, to developing and perfecting the beers before we release them to the drinker.”