Jimmy Buffett Recalls Wild 1970s Key West Literary Scene In ‘All That Is Sacred’

The YETI-produced YouTube short film features Buffet, Thomas McGuane and others remembering Key West’s artistic heyday.

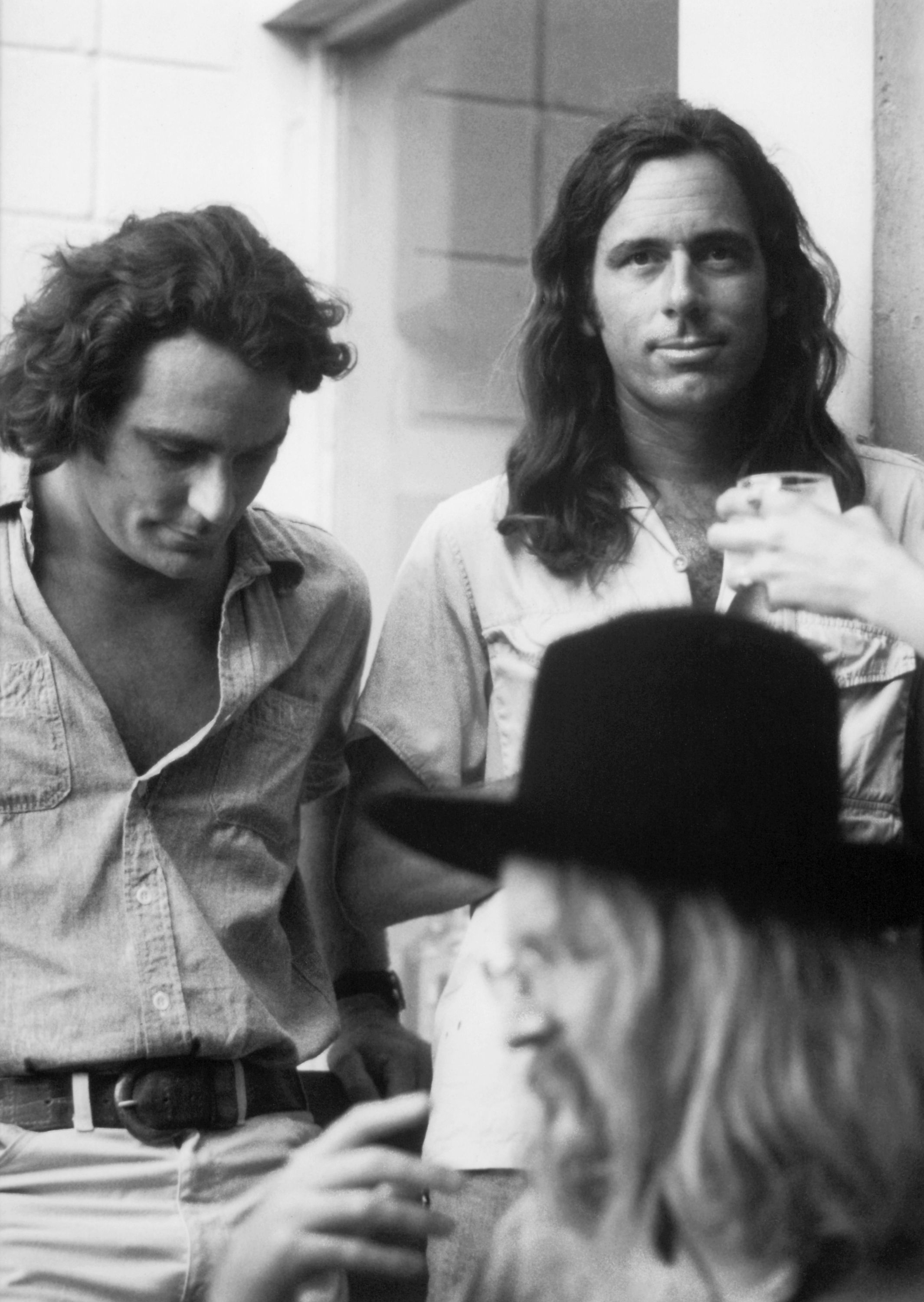

All That Is Sacred premiered last year at the Telluride Film Festival, and the YETI-created doc just released widely on YouTube. It’s a film that will appeal to lovers of fishing, literature, and the lightning in a bottle that was late 1960s and early 1970s Key West. Poignant interviews with singer Jimmy Buffett and writers Thomas McGuane and Guy de la Valdene, combined with archival footage, make a worthy epilogue for a place and time we owe some of our best books and music to—let alone our collective daydreams.

I spoke to director Scott Ballew about making the short film over two years. The inspiration first took root when a good friend gave him books by Tom McGuane and Jim Harrison. “I fell in love with their writing,” says Ballew, “and I just cold emailed Tom [McGuane] about making a film on him. The director then flew out to Montana and spent 8 hours with McGuane on his porch, earning his trust. “It became clear to me that this was a man who had some deep friendships, and that he hadn’t processed the loss of those friendships.” The biggest was with Jim Harrison, a fellow Michigan native and a close friend of McGuane’s for over 50 years. McGuane describes the friendship [and healthy competition] with Harrison as a “brain channel that is not there [anymore].”

Digging into the two writers’ shared past in Key West, Ballew went “down a rabbit hole” of the 1973 fishing film Tarpon, a little-known art film that features McGuane, Harrison, and even Jimmy Buffett—who also did the music for the film in exchange for a free trip to France. “You wouldn’t realize Jimmy Buffett is in it,” says Ballew. “You could watch the whole film and not know it was about anything other than Tarpon fishing on the flats around Key West.

Tarpon was not an easy film to find. YETI founder Ryan Seiders had one of the only known copies. “I think it was the only DVD he owned,” says Ballew, who knew Seiders because he started the film program for YETI, and has made nearly 100 outdoor films for the company. Tarpon became Ballew’s only visual representation of the era, and he restored and used extensive footage from it in his film.

“What my film ended up being, in a way, was making the film [Tarpon director] Christian Odasso wanted to make—the lives of these writers in Key West but told 50 years later. How fleeting that era was and what the friendships became.”

While making the movie, McGuane got injured and Ballew couldn’t film him. The director needed to pivot, and McGuane’s wife—Jimmy Buffett’s sister, Laurie—had keyed Buffett into the project, and he got excited about it. Ballew believes Buffett’s enthusiasm came from the fact that it offered a chance to tell his origin story in a way that his success had obscured over the years.

“Very few people are aware that [Buffett] was a gritty struggling writer and a vagabond,” says Ballew. “He played for beer, and you couldn’t get him to tune his guitar,” remembers McGuane in the film. A lifelong Buffett fan, Ballew describes his first meeting with Buffett—a dinner at the restaurant La Condesa in Ballew’s hometown of Austin—as “surreal.”

Buffett was generous with his time, sitting for two interviews—one just six months before his passing. Buffett’s interviews take on far greater meaning in hindsight: “Losing people on a pretty regular basis now, I can’t believe that I am this old, but I feel a lot younger.”

Buffett passed away the night the film premiered. De la Valdene, the co-director of Tarpon and close friend of the gang who spoke movingly in Ballew’s film, died a week after it was finished. “They both got to see it before they died,” says Ballew.

For a 34-minute film, it packs in far more emotion and power than its running time might imply. I asked Ballew if he thought it gave some needed closure for the creative Key West crew of the late 1960s and early 1970s. “100 percent,” he said. “Jimmy started bawling one day thinking about Tom teaching his son how to fly fish. Tom got emotional thinking about Jim [Harrison]. I don’t think they’ve ever done that,” says Ballew. “They weren’t guys that sat around and thought about the good old days, but this film forced them to do that.”

McGuane echoes the same idea in the film: “You have these congeries of people that get together for one reason or another, and the astonishing thing about it is that people disperse,” recalls McGuane, “You didn’t know it at the time, you just thought life would always be that way.”

If the film looks back with wet eyes at times, it also looks back with a smile. “We’re lucky to have had it happen,” said McGuane, “Most of us feel those were the best years of our lives.”