Twenty years ago, Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain published Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk, a scabby inside-look at the wildly fun, incredibly seedy and at times terrifying underbelly of the 1970s New York City punk scene.

The book’s groundbreaking oral history form (interviews with musicians, artists, groupies, and druggies who populated a scene that peaked with a hallowed creative fervor at CBGB in the mid-to-late 1970s) gave it an unmistakable raw power that was immediately recognized as something truly special.

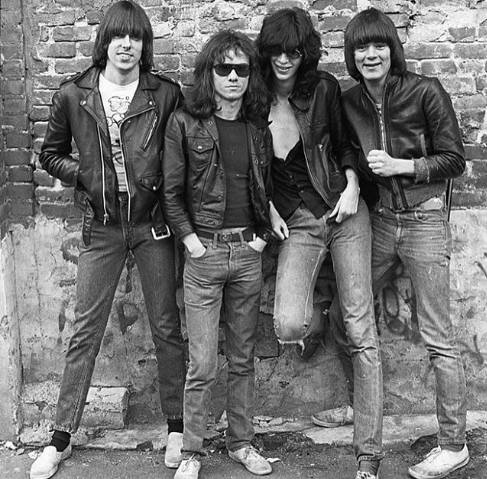

An instant cult favorite, Please Kill Me was even compared to the Bible: LA Weekly wrote that it “does For the Ramones what the disciples did for Jesus.” It was also applauded by leading mainstream outlets like the New York Times and The New Yorker.

To mark the book’s 20th anniversary, a new edition, filled with dozens of new interviews and an updated afterward, hit shelves in August (Grove Press.) Equally exciting for fans has been Please Kill Me: Voices From the Archives, an audio program in which selected interviewees—some now deceased like Lou Reed, Joey Ramone and poet/rocker Jim Carroll—can be heard talking about the bad old days.

(Example: Carroll jokes about wanting to punch Iggy Pop in the face on seeing him jump into the audience for the first time. There’s also Joey Ramone talking about hitchhiking through Queens dressed up in towering platform shoes and lacy women’s clothes during his early-70s glam period.)

“It was the immediacy of people in the room I wanted,” co-creator Legs McNeil—who was right there with the Ramones at the height of CBGB era as Punk magazine’s “resident punk,”—tells Maxim about the book’s oral history form. “I don’t want to hear some writer telling me how I should feel, I wanna hear the real story.”

Oral histories have since become a widely popular journalistic trope, and Please Kill Me is now considered one of the greatest rock n’ roll books ever written. Translated into 12 languages, it has sold about 500,000 copies worldwide.

“There’s no moral voice saying ‘you kids don’t do drugs,’” McCain explains of the book’s down-and-dirty appeal. “People want to read about people being badasses—I certainly do.”

Memorable first-hand accounts of iconic rock n’ roll moments—the New York Dolls transforming a moribund rock world or the Ramones exciting first gig at CBGB—are presented as neutrally as Dee Dee Ramone raving about how strong the French heroin was that he copped as a teenager, or model Cyrinda Fox bathing the abscesses covering the doomed and drug-addled rocker Johnny Thunders as he was passed out from too many downers.

Lending the feel of a cautionary rock n’ roll fairy tale, Voices From the Vault is narrated by actor and rocker Michael Des Barres in a plummy English-accent. The tone seems apt given that the savage streets of 1970s New York, when young aspiring poets and musicians could live cheaply on the then-decaying Lower East Side, which has since been transformed into an upscale hub of vibrant nightlife and luxury apartment buildings.

“Nothing like [the scene] could ever be repeated, its an impossibility,” McNeil says. Even when he was starting the five-year long labor of love that would become Please Kill Me, the scene was starting to seem like a fleeting memory.”

“It was like, ‘did this really happen?’” McNeil says. “A cloud was dissipating and I wanted to get what happened down before it disappeared altogether.”

But despite haunting CBGB and Max’s Kansas City almost every night in the late mid-to-late 1970s, sometimes what he heard shocked him. Like filmmaker Duncan Hannah’s infamous anecdote about the first time he met his idol Lou Reed at Max’s, and the proto–punk god asked him to take a shit on a plate.

“I didn’t know half these stories—it was just getting together with Duncan and turning on the tape recorder,” McNeil says with a laugh. “I think Lou was just fucking with him.”

Another darkly hilarious tale is set at a June 1971 Stooges gig at Electric Circus on St. Mark’s Place. After coming on stage late because Iggy was stuck in the bathroom trying to find a vein to shoot up in, the band played the same song over and over again.

“Iggy just looked at everybody and said, ‘you people make me sick.” Then he threw up,” relates Dee Dee Ramone, who was in the audience.

“It was very professional, I don’t think I hit anyone,” Iggy says.

The raw and ragged three-chord sound coming out of CB’s was booze and drug-fueled but ultimately guided by what McNeil calls, “inspired amateurship.” Acts like the Ramones, the Heartbreakers, Blondie and the Dead Boys created nights at the small graffiti-splattered Bowery rock club that continuously topped each other.

“[We] wondered if it could get any better and each night it did,” he says. “It was even more fun and more interesting than people think it was.”

But things quickly took a dark turn. Stymied by lackluster industry interest, poor record sales performance and the music industry’s toxic view of punk created by the controversial Sex Pistols, frustrated musicians increasingly turn to cheap and readily available heroin.

Nancy Spungen was knifed and bled to death in her room at the Chelsea Hotel and Sid Vicious, the suspected culprit, died of a drug overdose before he could go to trial. When high-purity cocaine and the deadly AIDS virus entered the mix in the 1980s, things really went downhill.

By the late 1980s so many of the Please Kill Me (the title is taken from a t-shirt designed by Richard Hell) characters in the book have died of overdoses, misadventure and illness the body count seems excessive even taking into account risky behaviors of cheap drugs and easy sex.

The reader can only speculate if the highly malignant cancers that lethally ravage the young punk beauty Anya Philips and later New York Dolls drummer Jerry Nolan are AIDS-related, but it seems likely. In a freak accident, Dead Boys frontman walks away from being hit by a truck in Paris only to drop dead later that night.

Of those interviewed in the book, 42 people have now died. “Its kind of a drag.” McNeil says. (The fallen now claims Lou Reed, all four of the Ramones, Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan and Arthur “Killer” Kane of the New York Dolls, Ron and Scott Asheton of the Stooges.) I ask him if there is any way the punk’s later suffering can be detached from all the fun.

“That’s like saying does real life to be tied to suffering and I think the answer is yeah,” he says. “No one gets out of here alive—we all go through shit.”