These Photorealistic Bird Paintings Are Inspired By The Work Of Famous Artists

From a Mark Rothko-style pelican scooping up its prey to a racing pigeon painted with the colors of Gerhard Richter’s landscapes.

(Clive Smith)

A world beyond animal extinction is on view in NYC through June 4. Clive Smith’s second solo show at Marc Straus gallery on Manhattan’s Lower East Side looks as much like a natural history museum as it does an art exhibition.

Around the room, carefully framed canvases portray birds in vibrant hues with startling photorealism, each accompanied by a fine metal plate detailing their scientific Latin name.

Look a little closer at these owls, pelicans, and pigeons though, and you might realize they can’t actually be real. The species displayed across Smith’s Speculative Bird Paintings take their names and plumage from late legendary painters across art history—Bridget Riley on one duck, Kenneth Noland on an owl.

(Clive Smith)

A pelican inspired by Mark Rothko scooping its prey from the sea, with outstretched wings, the horizon line, and fish for dinner—all gorgeously aligning with the colorfield painter’s compositional structure. These works are Smith’s rebellion against the laws of nature.

Smith originally hails from the U.K., but working in fashion brought him to New York. “I soon realized that clothing design wasn’t fulfilling me and I started going to life drawing classes on the weekends,” Smith tells Maxim. “I started painting full time as soon as I financially could.”

“In 2007, I first started painting people in manipulated landscapes,” the artist continues. “I didn’t completely take the human image out of my work until I started painting bird nests on ceramic plates around 2014.”

(Clive Smith)

Smith’s latest series arose from the story of the Passenger Pigeon. “I came across the Revive and Restore project that is working on the idea of de-extinction,” Smith says.

“They hypothesize the Passenger Pigeon could be the model species to bring back to life through synthetic biology. Using the DNA from Passenger Pigeons in natural history museums, they speculate that one day they will be able to genetically edit this DNA into its closest living species—the Band-Tailed Pigeon—and breed a new generation of Passenger Pigeons.”

“I started to speculate that if biologists could do that, we could extract the DNA from a famous works of art and gene edit it into a bird species that could have similar feather patterning or body structure,” he continues. “I could breed my own generation of Masterpiece Birds with pigment and oil.”

(Clive Smith)

Birds are extremely sensitive, and are often the first species to signify environmental change. When bird populations plummet or shift, you know something’s up. “They travel great distances which makes them useful for identifying ecosystem health,” Smith adds. “Birds are beautiful, but when you closely study them, they are also strange. You can still see their dinosaur ancestors.”

Sometimes he starts with a bird in mind and other times he starts with a work of art. Smith cites his Richter Pigeon as a pairing that made particular sense: “Gerhard Richter’s landscape paintings of the German countryside have a blurry feel to them, like a snapshot from a moving train, so I immediately thought of speed and Racing Pigeons. And because of world history when I thought of trains and the German landscape, I thought of World War II–pigeons were used in both world wars to send messages to the front.”

Other ideas require more maneuvering–Smith knew he wanted to honor Josef Albers, the inventor of modern color theory, but Albers’s square artworks required certain specifications. “I explored water birds as they have generally a large body, and the square feathered patterning worked well with a duck’s body,” Smith says.

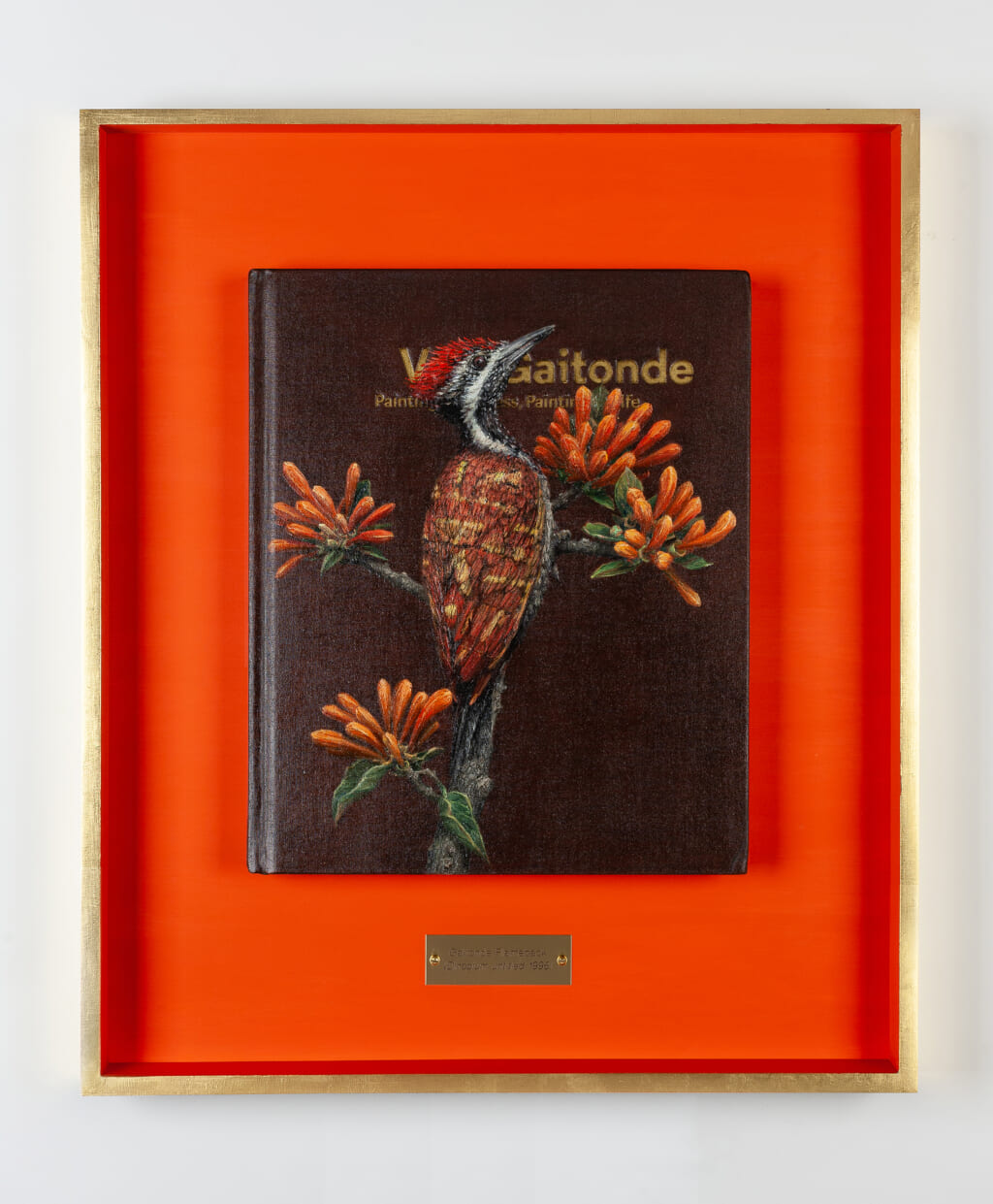

Smith hopes viewers build intimate relationships with each canvas. The Richter Pigeon in particular employs trompe l’oeil so it appears the bird is stepping straight out of its frame, demanding viewers take a closer look. The artist has even framed a series of scientific volumes featuring preliminary studies for the show’s fantastical inventions, available for flipping through.

Smith hopes most of all, however, that this series inspires people to examine our power to affect Earth’s ecosystem on purpose. “I don’t think the majority of people know that the apples they eat only exist because a human has grafted that flavored apple onto a root stock, or that through breeding humans created a French Bulldog from a wolf,” he says.

“Although I feel I no longer need to paint the human image in the works, the paintings are still about us.”

(Clive Smith)