How To Pair Wine With Your Favorite Comfort Foods

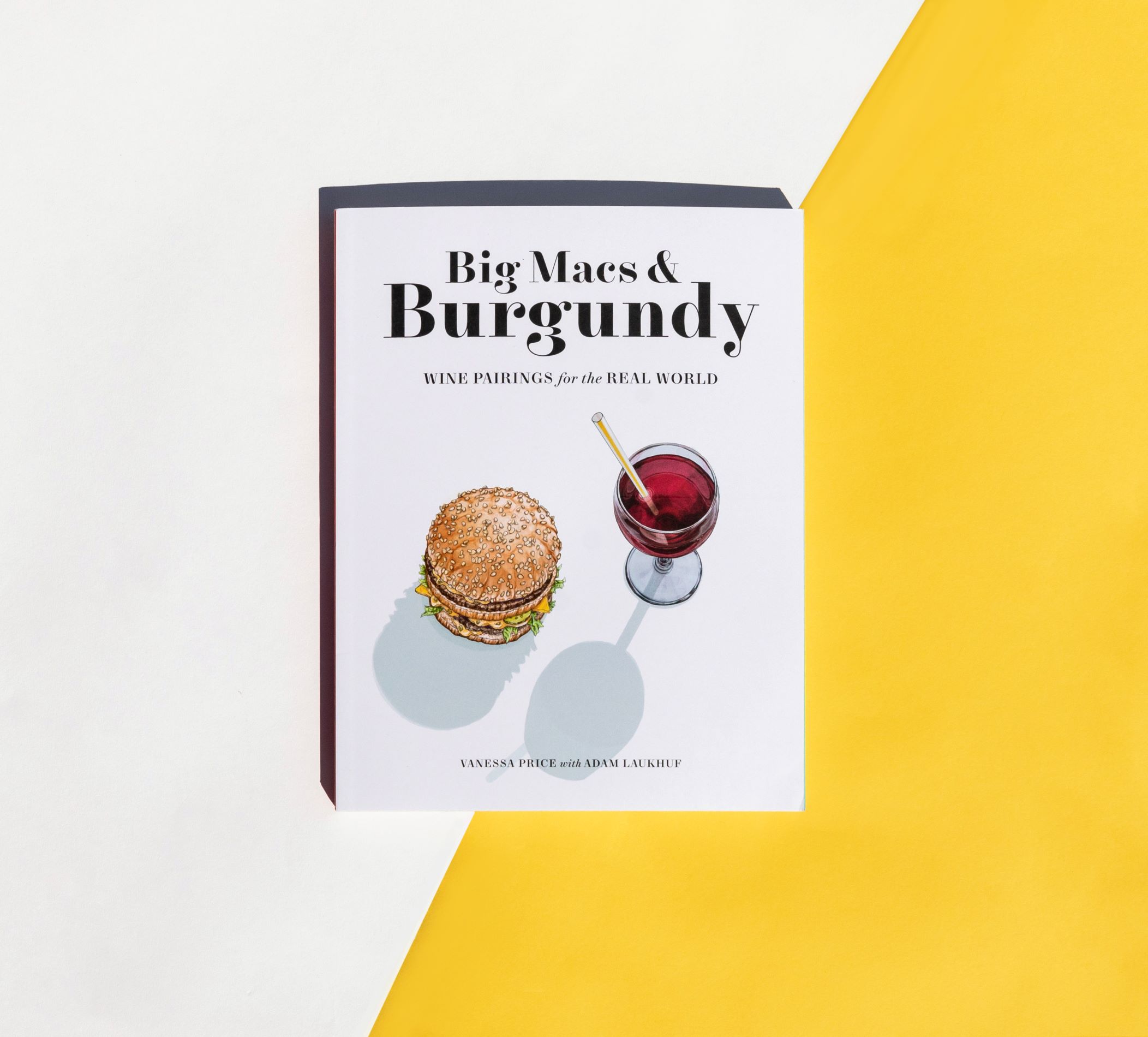

The new book “Big Macs & Burgundy” shows how to pick the right wines for burgers, pizza, ribs, mozzarella sticks, pigs in a blanket, chips, dips, and more.

Big Macs & Burgundy: Wine Pairings for the Real World, can transform you into an expert at pairing wine with just about anything, from pizza and Lucky Charms to pad thai and Popeye’s. Veteran sommelier Vanessa Price and co-writer Adam Laukhuf’s genius new book demystifies wine-speak and answers the age-old question that confounds us all: what should I drink with this?

You’re going to want to try surprisingly delicious combinations like Cheetos with Sancerre and Half Baked with aged Rivesaltes. There are also perfect wine picks for all your favorite stuff at Trader Joe’s and all your favorite cuts of cow, not to mention fish tacos and Peeps. Refreshingly funny and written in language anyone can understand, it just might just be the only wine pairing book you’ll ever need.

Because the only safe place to throw a party these days is in your mouth, here’s some of our favorite Big Macs & Burgundy pairings, with excerpts and illustrations from the book:

Mozzarella Sticks & Austrian Zweigelt

Whether or not to add the marinara to your fried tubes of questionably real mozzarella is a very personal decision, and I respect your choices, but I’m going to assume you’re a dipper. The most important thing to keep in mind with mozzarella sticks is that their shells are usually packed with ground Parmesan, herbs, and black pepper. That distinct Italian flavor profile, combined with the greasy crunch, creamy center, and sharp red-sauce finish, has an ideal bedfellow in Zweigelt from Austria.

A bright, violet-hued cross between Blaufränkisch and St. Laurent grapes, it’s the most widely planted red grape in the country, and it embodies all the characteristics you need for fried cheese. Don’t let the crazy name scare you. It’s pronounced the way you think—zwhygelt—which is only moderately easier on the tongue than Rotburger, its original name before 1975, when they rather inexplicably decided to rename the grape for the Nazi who invented it in the 1920s, Fritz Zweigelt.

A red with soft tannins and a medium body, Zweigelt is packed with red cherries, cinnamon, and violets, with a juicy freshness and a firm thrust of acid that’s as saucy as it is demure. That unusual tension is one of the wine’s greatest attributes. Zweigelts are similar to spicy Beaujolais or richer Pinot Noirs, but also aren’t entirely like either one.

They’re in their own category, much like our fried wonder wands. The Italian herbs in their breadcrumb-coated crust highlight the black licorice and ground pepper notes in the wine. And in turn, the Zweigelt’s red fruit and sweet baking spices sing a vibrant falsetto with the marinara’s tangy soprano, which straddles that hair’s breadth between savory and sweet that keeps us dunking.

BBQ Ribs & Côte-Rôtie

BBQ is in my blood, and I genuinely believe that the act of pit-smoking giant slabs of meat is one of the world’s great culinary art forms. I also know that there are many bottles that can amplify the smoky, fatty sublimity of perfect brisket or a rack of tender ribs. But one above all, Côte-Rôtie from the Rhône Valley of France, can help BBQ achieve transcendence.

The Rhône Valley is a diverse, dynamic region that stretches approximately 120 miles north to south and can be cut in half both geographically and stylistically. The southern part makes wines that are based on the grape Grenache and can have a lot of other red and white grapes blended in. But in the north, it’s all about the magnificent red grape we call Syrah.

Within the northern Rhône, there are five smaller appellations—each with its own distinct characteristics and idiosyncrasies—that use Syrah as their base. What makes Côte-Rôtie such a unicorn among them is actually explained in its name. In English, it translates to “the roasted slope,” because the steep inclines where the vines grow face south toward the Rhône River and get a lot of sunshine. That allows the grapes to ripen to their full and most powerfully tannic potential, and the resulting expression yields a robust set of aromas and flavors like olives, white pepper, bacon fat, and black fruits of all kinds, along with a distinct smokiness that’s a dead ringer for charcoal.

No matter what type of barbecue you love, these wines will get the very most out of every juicy, smoky hunk. The appellation is small and prestigious, so the wines start on the pricey side and only go up from there. But Côte-Rôtie is so consistently good, you get what you pay for every time.

Pigs in a Blanket & Margaret River Chardonnay

Let’s be clear. You’re free to get as fancy as you want, but the only true pig in a blanket in this world starts with a Hebrew National mini-frank and ends with Pillsbury Crescent Roll crust. All other versions are mere pretension. Since the beginning of time, these two crucial components have achieved that juicy-hot, flaky, buttery, and scrumptiously dippable bite every time.

Margaret River, located in the southwestern corner of Australia (opposite side of the continent from Sydney), produces some of the best versions of the world’s most ubiquitous white, Chardonnay, even though it has scarcely fifty years under its winemaking belt.

The top wines from this region can age as long as white Burgundy, yet still have more approachability in their youth, when white Burgs can be austere and unapproachable. So they are easier to drink young and still able to go the distance—just the kind of bewitching characteristics that might convince you to break up with your steady Old World Chardonnays (or at least consider an open relationship).

Margaret River’s zesty freshness creates a fulcrum with the fat of the frank and the flake of the dough, and its savory profile works in tandem with the protein. The saltiness of both lingers softly, just long enough to leave you salivating for another bite and sip.

Seven-Layer Dip & Salta Malbec

Mendoza Malbec is everywhere you look. From $5.99 grocery-store bottles to wood-aged versions going for triple digits on menus, these Argentine wines are as easy to find as California Cab and just as wide ranging in quality. But there are plenty of regions in Argentina other than Mendoza making really good Malbec, with identities all their own. One of my favorites is Salta, an appellation that’s home to some of the most spectacular vineyards in the world.

At 10,207 feet above sea level, Salta can also lay claim to the second-highest elevation vineyard on the planet (there’s one higher in Tibet), with less rainfall than the Sahara Desert. The vines are so far up that on most days there simply aren’t any clouds to shield the grapes from the beating sun, but Salta’s extreme altitude produces temperatures cold enough to counteract the intense solar exposure. It’s a bit like the difference between a bad burn and a nice tan.

The area is so remote it wasn’t exposed to the phylloxera louse that devoured the vines almost everywhere else in the world, meaning some of its grapes are still on ungrafted rootstock. Some argue this gives the wine a purer flavor and vibrancy; others think it’s marketing. I think it doesn’t hurt, so why not?

Salta produces only about 1 percent of Argentina’s wine, but it’s worth the effort to find a bottle, especially if you’re making seven-layer dip anytime soon. Refried beans, sour cream, cheddar, guacamole, tomatoes, green onions, and black olives on a tortilla chip confront you with so many textures and flavors, only the high-altitude moxie of a Salta Malbec will do.

Salta differs from the Argentine Malbecs you might be used to because its grape skins are so much thicker, making for chewier tannins that have enough might for dishes with texture overload and a thicker, fleshier wine that requires a few more chomps to take down. The juice inside is roaring with acidity, which gives the tomatoes a bit more salsa. And the dark magenta color and concentrated structure produce wafting fruits that are almost as black as the olives.

The Hot Brown & Patagonia Pinot Noir

We borrowed it from Austin and Portland, but the local business slogan in my Kentucky hometown is “Keep Louisville Weird.” And I love that my people lean in, at least when it comes to their arteries. The Hot Brown was invented at an iconic spot in downtown Louisville called the Brown Hotel as a late-night snack for revelers who attended its huge dance parties in the 1920s.

And though you might visit Derby City for the big race or the bourbon, I have to insist that you make a stop at this local landmark to try its namesake dish. It’s an open-faced sandwich on Texas toast with turkey and bacon smothered in Mornay sauce, which is basically an ungodly amount of butter, heavy cream, and Gruyère cheese with a pinch of nutmeg and paprika. It all gets broiled until the bread crisps and the sauce, well, browns. And it’s just as gloriously weird as it sounds.

The wine to drink with it, Patagonia Pinot Noir, was not made by the same company that supplies hedge funders with their favorite vests. The natural wonderland of Patagonia in Argentina is the southernmost wine-producing region in the Americas, and its arid valleys make some of the best Pinot Noir in the world. Its extreme winters and cool summer nights make for a prolonged growing season that’s particularly well suited for Pinot. Bright and high toned enough for that thick Hot Brown sauce, it’s also notable for its earthy undercurrents, which the turkey and bacon lap right up. A dish so rich needs all the tannin and acid you can muster—and Patagonian Pinot delivers those by several lengths.

If a visit to the Brown isn’t in your immediate future, think about similar iterations of grilled bread, cheese, protein, and rich sauces. A decadent croque monsieur can do a tasty tango of its own with this lithe Argentine.

Reprinted from “Big Macs & Burgundy: Wine Pairings for the Real World” by Vanessa Price with Adam Laukhuf. Photographs by Michelle McSwain. Illustrations by The Ellaphant in the Room. Published by Abrams Image, an imprint of ABRAMS.