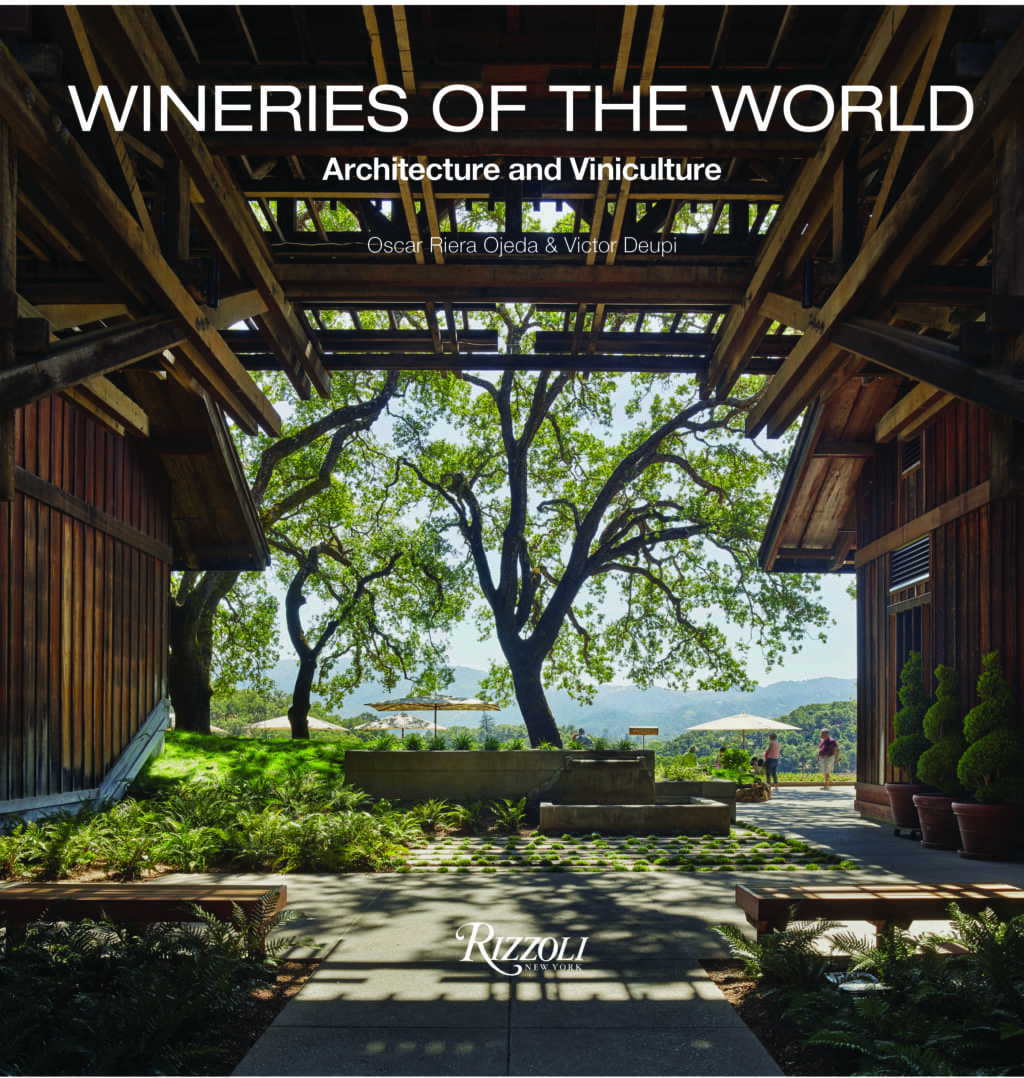

Take a Virtual Tour Of World’s Most Amazing New Wineries

These wild wineries showcase both fine wine and killer design.

(Rizzoli)

Twenty-five beautifully designed wineries by contemporary architects from around the globe form the basis of one of the season’s chicest new books—Wineries of the World: Architecture and Viniculture by Oscar Riera Ojeda and Victor Deupi.

Impeccably published by Rizzoli, the wineries on display in the book run the gamut from state-of-the-art structures in Napa Valley and an Italian winery estate in the hills of Tuscany that marries technology with tradition, to an Australian enterprise “at the cutting edge of organic viniculture,” all examples of the “finest taste in both wine and design.”

(Rizzoli)

Rather than “repeat established, even ancient traditions cultivated over centuries throughout Europe,” Rizzoli notes, “the contemporary architecture of wine has become a modern celebration of place, reflecting the topography of the landscape in which a winery is situated, the agricultural heritage, and at times the regional vernacular.”

As Deupi, who teaches architectural history, theory and design at the University of Miami School of Architecture puts it, “Architecture and wine have been intimately connected since the very earliest societies serendipitously discovered that the fermentation of grapes was in fact a gift of the gods.”

(Rizzoli)

As for the modern winery, “there are few building types today that are so universally cherished and loved,” he notes. “Typically found throughout the world where pastoral Arcadian landscapes allow for the cultivation of grapes or vine-growing, there are as many differences in the premises that accommodate the simple art of winemaking as there are in the regional, climatic, and topographical conditions that encourage the planting of vineyards.”

(Rizzoli)

Although winemaking can take place in a variety of buildings and locations, “the structures that house such processing facilities require greater sophistication today, as they must [not only] respond more efficiently to energy and resource consumption, material lifespan and green building practices,” Deupi points out, but also “suit the particular winemaking processes of the estate, and provide a compelling image that is universally recognized as part of the ever-expanding tourist and consumer market for wine.”

Antinori Winery / Archea Associati / photo © Pietro Savorelli, Leonardo Finotti (Rizzoli)

Certain traditions go back centuries, as “at least from 1400 onwards, many of the wine-producing families, chateaux, and names we celebrate today came into prominence,” he writes. “The rise of international banking and the establishment of credit throughout the Mediterranean made Florence the financial capital of Europe. Banking families such as the Antinori in Tuscany not only had a splendid new palace designed in the center of Florence…. but since the late 14th century had also been producing wine on their substantial Tuscan properties.”

Antinori Winery / Archea Associati / photo © Pietro Savorelli, Leonardo Finotti (Rizzoli)

It was in the latter half of the 19th century that the term “winery” came into common usage, Deupi notes, “and the architecture of wineries began to develop along the same stylistic lines that were fashionable in architecture in general. One could find all’antica (in the manner of the ancients), Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, and Neoclassical buildings, exotic non-western stylistic variants, as well as rustic vernacular forms, wherever grapes were being grown and wine was being made. This pattern lasted well into the first half of the 20th century even though economic uncertainty, political upheaval, and the Prohibition movement disrupted wine production and trade throughout the world.”

photographed by Tomas Manina and Juraj Bartos

(Rizzoli)

Deupi, who with this book has firmly established himself as one of the foremost experts on the subject, goes on to explain that “the second half of the 20th century saw modern winemaking reach new heights of prosperity,” while architecture “became a necessary vehicle for renovation, expansion, and the creation of an up-to-date corporate or family identity.”

In this new era, “Northern California took the lead in the development of the modern winery through a series of bold investments and innovative designs.” Soon wineries around the world began experimenting with architecture.

The list of celebrity architects commissioned by well-known wineries since then includes the likes ofZaha Hadid, Renzo Piano, Santiago Calatrava, Ricardo Bofill, and Lord Norman Foster, among others. Deupi points to two standout projects that “not only represent the celebrity culture of contemporary architecture, [but] have also become synonymous with the world of modern wineries and the variety of approaches that are possible.”

The first is the Dominus Winery in Napa Valley, designed in 1994 by famed Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, who imbued the minimalist stone-walled structure with an “enigmatic sense of monastic simplicity.”

And In 2005, Frank Gehry completed what is perhaps the coolest winery ever created, for Marques de Riscal in Rioja, Spain, which is also a world-class, five-star resort and is part of Marriott International’s Luxury Collection—as featured in our 2020 article on the World’s Most Beautiful Hotels.

“These two projects reimagine the winery as a bold experiment in architecture and landscape, technology and innovation, agriculture and industry, hospitality and heritage,” Deupi enthuses.

More recently, he notes, “wineries have begun to explore less monumental and expressive forms of architecture and have instead embraced more nuanced approaches to cultural landscapes, green viticulture, justifiable building systems and materials, and vernacular architectural contexts,” which the authors decided to focus on for this book.

And in the best of them, he writes, “the care and craftsmanship that is so clearly discernible in the making of these modern wineries is equivalent to the attention that is given to the cultivation of grapes.”