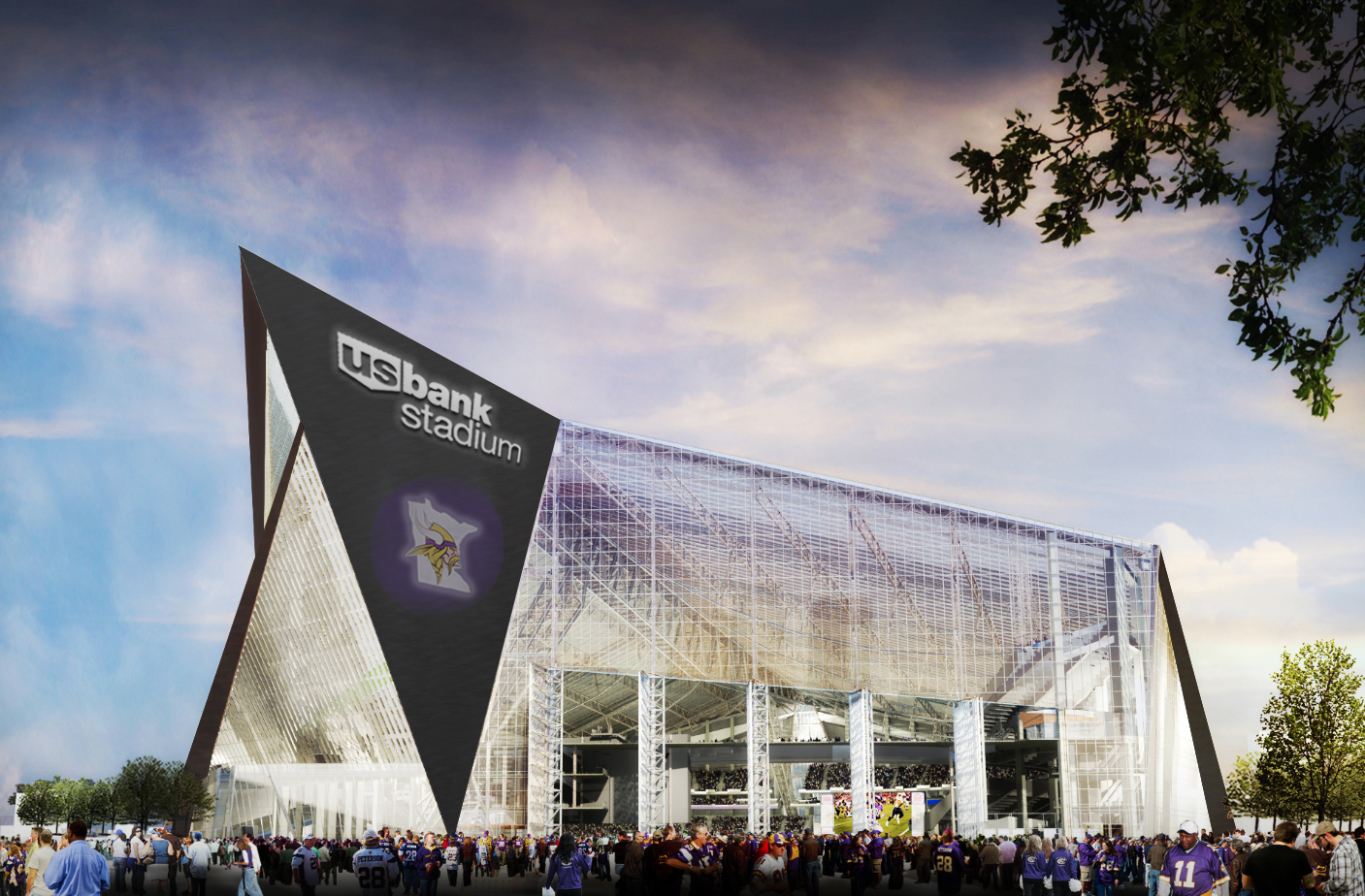

Inside the NFL’s Most Technologically and Architecturally Advanced Stadium

The Minnesota Vikings’ new home is a glass-roofed, fully-wired wonder.

In early March, the Minnesota Vikings’ new stadium, named in honor of legendary head coach U.S. Bank, is a dusty bowl of activity. The field where Teddy Bridgewater will try to lead the team back to the playoffs is covered in dirt. The concourses where fans will impatiently wait for beer are barren. The 66,200 purple seats where those same fans will plant their warm, dry asses—not to be taken for granted at a Midwest football game—are covered in giant sheets of plastic. This $1.1 billion behemoth is only four months away from its grand opening and there’s a lot of work to do.

By the time U.S. Bank Stadium opens in July for Luke Bryan’s country boy jamboree, it’ll look a gleaming palace in Minneapolis’ desolate Downtown East. But the real achievements will be less visible in this high-tech playground that promises to make other NFL stadiums look like abandoned livestock arenas. From roof to field, the Vikings new home will be an architectural and technological marvel meant to attract attention and attendees from around the world.

But on this uncharacteristically balmy late-winter day, it’s still got a ways to go. The stadium is an active construction site, which is why the writers touring it are playing dress up with protective glasses, yellow vests and hard hats. The headgear is shiny and purple with a Viking horn on either side, a stark contrast from the union stickers and deep scratches on the hats of the men and women working here. Even with the work left, about 10 perfect we’re told, the team is ready to show it off. And it should be; this place is an impressive sight—especially if you know where to look.

Up is a good place to start. Like the Metrodome, the drab arena torn down in 2014 to make way for the new stadium, there’s a roof on this cavernous building. Unlike the Metrodome, this place lets you see the sky. That’s because sixty percent of the stadium is covered with a transparent plastic called Ethylene tetrafluoroethylene, or ETFE.

Designed by Dupont for use in industrial aeronautics, ETFE has become a trendy roofing material around the world. The lightweight, tear-resistant film can be found atop Beijing’s Watercube and Munich’s Allianz Arena. U.S. Bank is the first American stadium to use it on this scale and the effect is dramatic. Even with the sun hidden in the clouds, the stadium bowl is illuminated with natural light and protected from the natural elements. In a city that barely gets above 40 degrees five months of out the year, that’s a big deal.

Especially since the stadium will be used for much more than football. The Vikings, in a best-case-scenario, would need it 12 days out of the year. Football games can be held outside but the civic and community events that will eventually be on the same floor can not. A dome will also allow Minneapolis to host the Super Bowl in 2018 and the Final Four the year later. Attracting marquee events and opening the doors to more than Vikings fans is an important part of justifying the eye-popping $500 million public money poured into its construction.

If the roof is the architectural headliner here, its five giant glass doors, ranging from 75 feet to 95 feet tall, are a damn good opening act. Even when they’re closed, as they were during the tour, these doors do a lot to eliminate the confined airplane hanger feeling you’ll find in most domes. But when these 57,000-pound beasts open up, we’re told, it’ll truly feel like you’re outdoors. Something like playing football in your garage with the door up.

“The ETFE roof gives fans the best of both worlds” the team claims in press material, “an outdoor experience in a climate controlled environment.”

One demographic that may not appreciate these oversized windows is Minneapolis’ avian community. Animal rights activists have crowed about birds colliding with the glass, calling the stadium a “death trap.” A slight exaggeration perhaps ,but there’s little doubt some dumb birds will kill themselves by slamming their skulls into the giants panes of glass. The question is how many and what should be done about it. One high-tech idea—what other kind would there be?—is to cover the stadium’s 200,000-square-feet of glass with an infrared film designed by Minneapolis’ own 3M. Invisible to the human eye, the film would serve as a giant warning sign to birds.

Back inside the stadium, we wind our way through through tunnels and into luxury boxes, catching a glimpse at a club level where wealthy fans can cloister themselves off from the hot dog-breathed masses. In here it’s easy to forget about architectural grandeur and one assumes that’s just what fans will do. The in-stadium experience will be on their mind and more and more, that means getting online.

The Vikings have given a lot of thought to the internet. So much thought that you’d be excused for thinking the team’s expecting you to look at your phone more than the field. Not so, says John Penhollow, VP of corporate and technology partnerships .

“We accept that fans are going to be on their phones. Our hope is that when they look at them, they work,” Penhollow says. To that end, the stadium will be equipped with around 1,300 internet access points installed in clamshells that will be affixed to hand rials. This, Penhollow insists, will allow the 30,000 fans expected to get online at each game to do so without trouble. It better. The system can also be supercharged for major events like the Super Bowl, allowing as many as 70,000 people to simultaneously tweets complain about the halftime show.

Surprising as it is, a reliable internet connection is a rare commodity in today’s stadiums. The Vikings are planning to take advantage of theirs by encouraging fans to get online, whether it’s to check their team in the fantasy lounge or to navigate the stadium with the team’s app. Designed by Bay Area-based VenueNext, the app will guide fans to and through the stadium, delivering information on traffic, parking, concession lines and bathroom occupancy. It will also communicate with beacons to provide location-specific notifications on things like sales at that team store you didn’t realize you were passing.

But if you think the app only exists to serve the fans, you don’t know how corporations use technology. As Vikings SMO Steve LaCroix explained, the app will also help the team track who comes to game. He proposed a hypothetical in which a fan attends eight games a year but buys all his tickets on StubHub or Craigslist. “We never knew who was really in each seat. The app helps gather information,” he says.

What will the team do with this information? Find that fan and try to sell him season tickets, of course. In a sense, it’s this aspect of the Vikings technological evolution that puts it closest to the cutting edge. There’s no better way to emulate America’s most successful tech companies than collecting information on your users and then trying to sell them something.