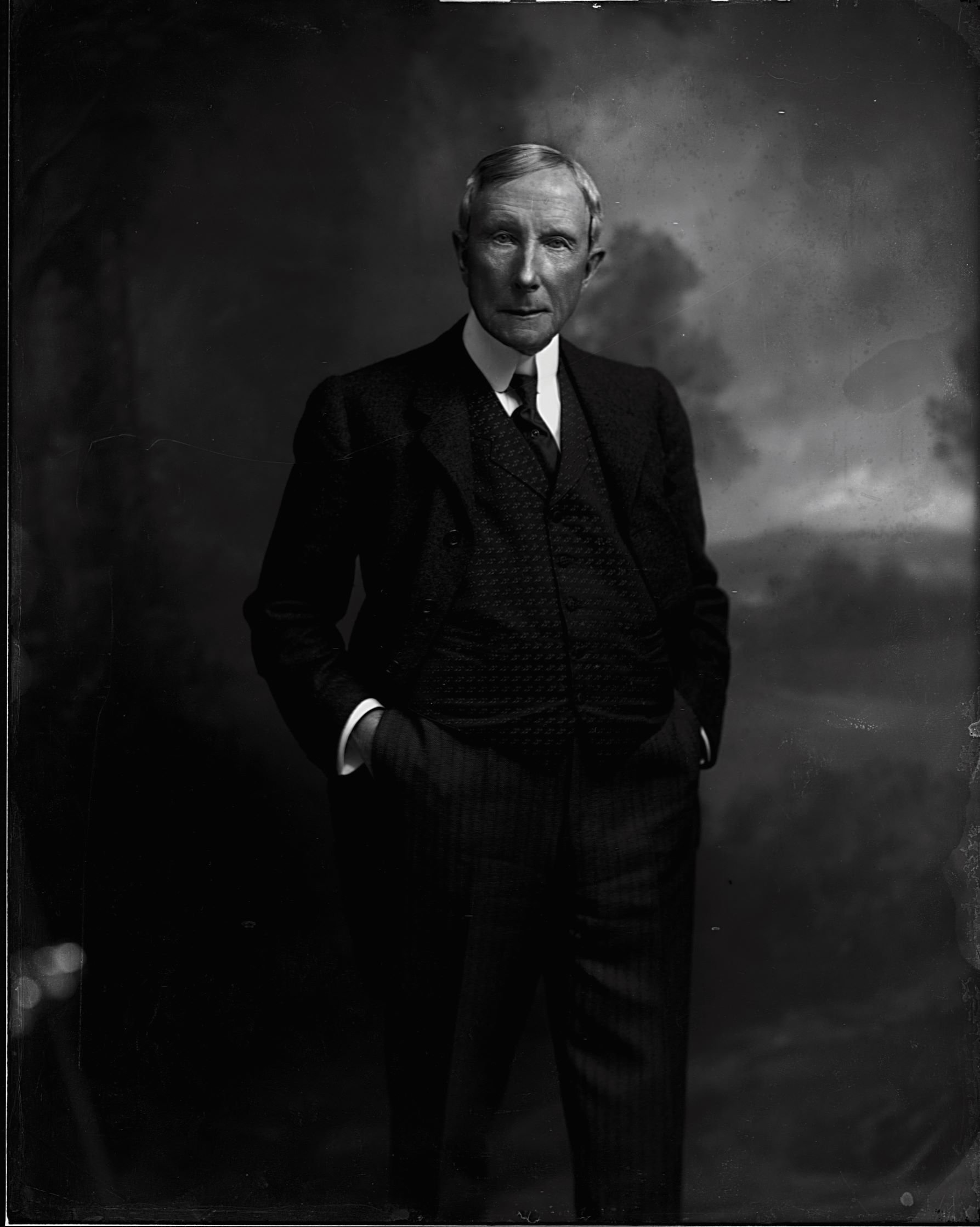

How John D. Rockefeller Set the Standard for Today’s Billionaires

The Standard Oil tycoon paved the way for modern moguls’ charitable initiatives.

There is perhaps no magnate who can be said to have had as important, and lasting, an impact on the modern world of business as John D. Rockefeller, whose influence is still felt on the American and global economy 120 years after his retirement. Most importantly, Standard Oil, the company he founded in 1870, not only built the modern energy industry, but created the architecture for today’s multinational corporations.

A century later, elements of Standard Oil live on as ExxonMobil, Chevron and many other companies that still dominate the global energy sector. Wealth from Standard Oil built major cities including Miami Beach, and funded some of the nation’s most dominant banks. And Rockefeller’s charitable foundation set the stage for modern philanthropy, medicine, and education, and tackled the greatest issues facing mankind in the 20th century.

Philanthropy became Rockefeller’s passion following his retirement from business at the age of 60—he lived to be 97—and he paved the way for the charitable initiatives that are so fashionable among billionaires today. Take, for example, the Giving Pledge, first established in 2010 and signed by dozens of the richest and most successful entrepreneurs in America. Since then, the charitable initiative has spread, not only to dozens of other American billionaires, but to some of the highest-net-worth individuals around the world who have taken a pledge to donate the majority of their wealth to philanthropic causes.

While the media, the public and others have rightly applauded their actions, the truth is only the need to make such ambitions public has any novelty. Far before it become popular, trendy or even good business to make such a public commitment, Rockefeller, a titan of unmatched financial and philanthropic impact whose very name is now synonymous with the ideas of success and wealth, did it privately.

While many know of John D. Rockefeller as the remarkable man who built the Standard Oil empire and became what some have called the richest man in modern history, not enough realize the almost unimaginably large impact his philanthropy, and philanthropic legacy, have left around the country and the world.

Rockefeller was born into unremarkable circumstances, in a small town in upstate New York, in 1839. After the family moved to Ohio in the 1850s, he dropped out of school and began working as a bookkeeper. He soon established his first business, a firm that sold produce such as hay, grain and meat, and thrived thanks to the demand created by the Civil War. By 1863, the hard-working young man was sensing a major opportunity was in the still-nascent oil industry, and began by taking a stake in a refinery near Cleveland.

Thanks in large part to Rockefeller’s insistence on a business that was both economical and efficient, his venture soon controlled nearly all of the refineries in Cleveland. Incorporated in 1870 as Standard Oil, the company founded by Rockefeller and his partners would soon grow into a behemoth. By the 1880s, Standard Oil controlled an estimated 90% of America’s oil industry. They did this by growing horizontally, buying up the competition, or simply pricing them out of business, taking more and more market share in order to form Standard Oil Trust in 1882.

They also grew vertically, however, eventually controlling much of the industry from drilling to driving, and acquiring assets up and down the supply chain, including oil wells, transportation methods, and even moved on to retail sales of products to customers. They even built their own oil drums and developed new uses for petroleum byproducts. Rockefeller’s genius was evident in his usage of economies of scale to enhance Standard Oil’s profitability and efficiency.

While there was no doubt as to the success of Rockefeller and Standard Oil, there was plenty of controversy over the methods which were said to have enabled their atmospheric rise. Rockefeller and Standard Oil became targets of the Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890 with the stated purpose of promoting free competition in the marketplace and preventing anti-competitive practices that hurt consumers and the economy as a whole.

While the company fought the legislation for some two decades, eventually Standard Oil was broken up into more than 30 companies, finalized by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 1911 ruling declaring the company in violation of antitrust laws—which did nothing to detract from his unprecedented success in business and industry.

Rockefeller’s true legacy was only beginning, however, on all fronts. Having retired from day-to-day business operations in the 1890s, he continued to keep an eye on his empire. With the invention and then the proliferation of gas-powered automobiles in the early 20th century, and the subsequent shift from kerosene to gasoline as the primary petroleum product as a result, Rockefeller saw his fortune grow to unimaginable levels. Some have estimated his fortune, adjusted for inflation, would be worth around $418 billion in today’s terms.

A devoutly religious Baptist, Rockefeller believed that God granted him this incredible bounty, and thus he felt a profound obligation to do good things with his wealth. “From the beginning, I was trained to work, to save, and to give,” he explained later in life. Rockefeller also admired his fellow tycoon, Andrew Carnegie, who had given away the bulk of his fortune in his later years, becoming one of the nation’s foremost philanthropists. For a man whom many in his day viewed as avaricious in the extreme, Rockefeller was in fact a man less intent on accumulating wealth than he was on best using his profits to help others.

Rockefeller was deeply charitable throughout his life, often personally reading the countless letters requesting money which he and his family received early in his success, before deciding whom to assist. While this was an example of his decency and desire to help the less fortunate, it wasn’t practical. For someone who had built his empire on efficiency and the economy of scale, Rockefeller’s philanthropy began disjointed and inefficient. By the 1890s the size of his fortune had made this scattershot philanthropy not only ineffective, but simply impossible.

“About the year 1890 I was still following the haphazard fashion of giving here and there as appeals presented themselves,” Rockefeller wrote in his 1909 memoir, despite the fact that by the year of publishing, he had already given away some $158 million to a range of causes and recipients. “I investigated as I could, and worked myself almost to a nervous breakdown. There was then forced upon me the necessity to organize and plan this department of our daily tasks on as distinct lines of progress as we did with our business affairs.”

As such, Rockefeller’s philanthropy, eventually organized into the Rockefeller Foundation, taking on the same level of efficiency and effectiveness that Standard Oil had previously reached. The foundation was seeded with $50 million worth of Standard Oil shares and given the mission “to promote the wellbeing of mankind throughout the world.”

Two men, Rockefeller’s son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and Frederick T. Gates, helped the titan imagine and create a modern philanthropic organization and suitable structure. In doing so, they essentially invented the model of large-scale philanthropy and the usage of scientific giving to determine appropriate recipients.

According to the foundation, “This new philanthropy did not seek to provide direct relief to the diseased or impoverished, but instead looked to systematic, scientific principles to cure the ‘root causes’ underlying both physical illness and social problems.” The organizations they created to guide these efforts were the forbearers of today’s global behemoths of philanthropy, in that they searched for enormous societal problems that only large, well-funded entities could battle.

The Rockefeller Foundation used the lessons learned in these early efforts, including the effectiveness of demonstration programs and infrastructure enhancement, to maximize their impact in the years that followed. From exploring the lack of education in the South for Black children in 1901, to today’s multinational, global philanthropic organization, there remains a consistent thread of at-acking large-scale problems utilizing the large-scale wealth accumulated and donated by Rockefeller.

In the century since, the impact of Rockefeller’s philanthropic fervor has only grown. There are of course the massive institutions that have benefitted from Rockefeller’s wealth, including Spellman College in Atlanta, the University of Chicago, which he helped found, and Johns Hopkins University, who founded their School of Hygiene and Public Health, the first of its kind in the U.S., with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. The foundation now has offices on four continents, maintaining a focus on public health while continuing to fund an array of partners that span the philanthropic and non-profit spectrum.

Today, the Rockefeller Foundation focuses its efforts on five extremely important missions: Nourishing People and Planet, Achieving Health for All, Ending Energy Poverty, Expanding Equity and Economic Opportunity, and Seizing Upon Emerging Frontiers. These serve as umbrellas under which the countless projects funded by the Foundation are organized, but they also harken back to the generosity, humanity and philanthropy inspired in the charity by its founder. Notably, for a company founded by the titan of oil, the organization has made green initiatives a major part of their goals for the future of the planet.

Many still don’t realize the impact that Ending Energy Poverty has had, and will have, on societies and individuals around the world, but the Rockefeller philanthropic efforts aim to change this. By accelerating access to reliable, renewable electricity, the foundation is able to jumpstart the lives and economies of low income communities worldwide.

Lights at home allow children to study at night, renewably powered irrigation can provide increased crop yields and food, while all businesses can grow more easily with a reliable source of electricity, especially in the modern age of the internet, computers, mobile devices and the digitalization of finance and currency. These efforts are led by the Power the Last Mile project, as well as advanced data analysis and global reach enabled by other projects such as Data & Technology Solutions and Driving Global Action.

Expanding Equity and Economic Opportunity have always been foundational goals in much of the Rockefeller Foundation’s work, but specifically they focus on two pathways to success in the country, and the world. The first is identifying and scaling both proven public and private sector economic policies, which often times require a large organization such as the Rockefeller Foundation to help connect, coordinate and educate the numerous stakeholders. The second is utilizing private capital and its power to grow economies in places, and with people, who need access to these types of grants, investments and capital.

And the Seizing Upon Emerging Frontiers section of the foundation focuses on maximizing the organization’s expertise and resources to take inventions, processes and technologies on the frontiers of science and figure out how to best utilize them to minimize inequities in the world. Just as the foundation was an innovator in large-scale philanthropy, it remains a pioneer by working through areas such as Climate & Resilience and Innovative Finance, which addresses the ability of global development to access private capital. As advances like cryptocurrency, blockchain, satellite internet and mobile banking continue to develop, the Foundation works to ensure that the most advanced ideas in the world are also helping some of the least developed areas of the globe.

So, while many of the same inequities and economic disparities endure in today’s modern capitalism, and today’s titans endure the same criticisms and accusations of monopolistic and anti-competitive practices, it’s important for society to not only focus on the enormous wealth of these modern age Rockefeller-types, but what they choose to do with their concentrated wealth.

John D. Rockefeller not only changed what the American and global economies would look like in the 20th century, but what large-scale philanthropy could accomplish globally. So the next time one hears about the Giving Pledge, and another billionaire committing to donate the bulk of their fortunes to charity, remember this isn’t a modern trend or concept, but one over a century old, sparked by one of the greatest industrialists, and philanthropists, the world has ever known.

Milton Friedman’s Monopoly Theory

Some of the most impactful economists and business minds of the modern era aren’t as critical of the way Rockefeller and Standard Oil handled their business as was the Supreme Court.

Milton Friedman, the famous economist and leader of the Chicago school of economic theory, once explained the complexity of such a broad term as monopoly, writing, “Exchange is truly voluntary only when nearly equivalent alternatives exist. Monopoly implies the absence of alternatives and thereby inhibits effective freedom of exchange. In practice monopoly, frequently if not generally, arises from government support or from collusive agreements among individuals… however monopoly may also arise because it is technically efficient to have a single producer or enterprise.”

Friedman explained that “When technical conditions make a monopoly the natural outcome of competitive market forces, there are only three alternatives that seem available: private monopoly, public monopoly or public regulation. All three are bad so we must choose among evils.”

Thus, Friedman points out that while there may be problems in capitalism caused by monopolies, there are few viable options to prevent them. Many experts also note that while encouraging competition and thus lowering prices is the goal of antitrust laws, Standard Oil actually lowered prices while dominating the market and exerting its control over the entire production, refinement and sale of their product. In other words: Rockefeller was right.