The man credited with being perhaps the most successful Wall Street investor and hedge fund manager in history—and perhaps the most intelligent billionaire in the world—has little interest in the kind of knowledge and information that is seemingly foundational to his peers in wealth management.

Simons, currently worth about $28 billion, is not solely focused on the stocks and other financial assets that Renaissance Technologies, the firm he founded in 1982, trades on a daily basis. He doesn’t delve into the detailed ins and outs of each trade, and in fact actively works to avoid trying to decipher the meaning and causes behind the buying and selling transactions of his firm—as he believes these attempts could contaminate the groundbreaking ‘quantitative investing’ system he crafted and that is the heart of the hedge fund.

This system has made him, his former colleagues, and the firm’s investors, annualized returns that are completely unheard of anywhere outside of Renaissance, making the firm the envy of other hedge funds and wealth management experts. In fact, within the walls of Renaissance Technologies, you’re unlikely to find many, if any, financial experts of the traditional sort. Instead, one is surrounded by mathematicians, physicists and other scientists, meaning that objectivity and scientific method replace the stereotypical economic theory and corporate analysis that largely define the investment industry and its leaders.

In other words, the last thing Simons wanted in his firm was Wall Street experience, expertise and methods. All he wanted within the walls were things he could always place complete trust in: math and science.

James “Jim” Simons was born in 1938 and raised in the Boston suburbs of Brookline and Newton. His parents, Jews of Russian descent, weren’t noted geniuses themselves, but it became clear when Simons was a young child that he had unusual intellectual abilities.

By the time he gained admission to MIT, Simons was a recognized math prodigy, excelling in advanced algebra, geometry, trigonometry and countless mathematical fields so sophisticated that even their names are indecipherable to most. (When did you last spend some time brushing up on differential geometry or holonomic systems?)

Finishing MIT in a mere three years, Simons was soon a shooting star in the academic community, completing his doctorate at 23; being named the head of the Stony Brook University math department at age 30; and winning the Oswald Veblen Prize in Geometry at 37—a crowning achievement in most careers. But he was just getting started.

It would be a few years before Simons decided to see how his problem-solving, infinitely-curious mind would perform in the mercilessly competitive world of Wall Street. By the time he was finished, though, the Wall Street establishment was pleading for mercy from his firm and from the “quantitative” form of investing that he helped create, shape and perfect.

In some corners of Wall Street, the term “quant” (short for quantitative analyst) is used in negative, or even derogatory ways. Many investors spend hours poring over financial reports, analyzing industry gossip and any information they can gather on the companies and financial instruments in which they invest, in order to gain an edge and find more success than failure, along with the attendant financial rewards.

Their dislike of quantitative investors is understandable in a way. Whereas traditional traders toil away to understand the seemingly endless number of variables that affect a stock’s rise or fall, their quantitative-focused competition apparently can’t even explain their own investments, strategies or trading patterns. Yet these “quants” often profit more consistently, and more significantly, than their counterparts using traditional trading models, despite having none of the analysis or corporate expertise standard across most of Wall Street.

Simons and his team at Renaissance have done all they can to remove any bias or prejudices from their investing. Rather than studying companies, they studied statistical economic trends. Rather than looking for the next hot stock, they were seeking market inefficiencies they could recognize from historical patterns. Simply, they were trying to take the influence of the investment community out of their investing, placing the power not with the insight of a human but the cold calculations of math.

It’s rumored to this day that even the coders who help create and maintain the algorithms behind the firm’s success aren’t even fully aware of the logic their computers use to decide when and what to buy and sell. Adding human intuition only risks contamination of the quantitative process. To get a sense of how successful Simons and Renaissance have been, the firm’s flagship Medallion fund is a “black box” which doesn’t provide information or insight into its methods, yet has returned an annualized rate of 39 percent after the (higher than standard) fees are taken out.

No other firm can offer this consistency or this return on investment. Other funds at the firm return impressive profits as well, but not quite at the level of the Medallion fund (which has been closed to non-employees or owners since the early 1990s), which according to some estimates has created over $100 billion in profits for its participants from 1988 through 2018. Simons relinquished daily control over the firm in 2010, but according to Forbes he “still plays a role at Renaissance”— which currently has around $50 billion under management—“and benefits from its funds.”

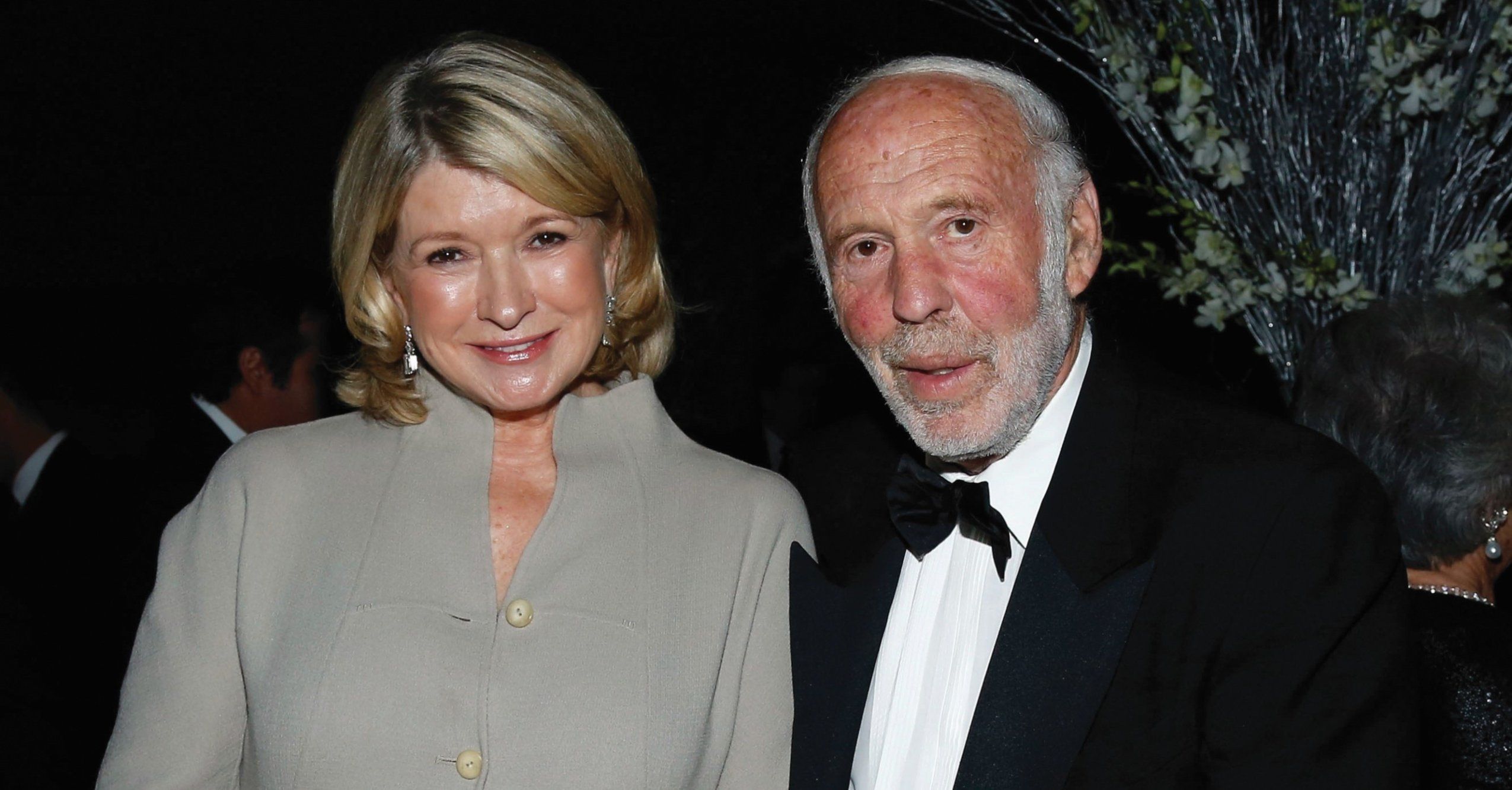

Beyond Wall Street, Simons’ philanthropic impact cannot be overstated. The Simons Foundation, the New York City philanthropy co-founded by Jim and his wife Marilyn Simons, was founded in 1994 with the goal of supporting basic scientific research—research whose only goal is to understand the phenomena of our universe.

To date, they have given away more than $5.2 billion to charitable causes, and the foundation is sufficiently endowed to continue giving at its current rate in perpetuity. While the scientists and institutions who receive grants are wide-ranging and diverse, they are all unified by pursuit of basic scientific knowledge and its power to transform life on our planet for the better.

The Simonses are also committed to education for and engagement with the public; the Simons Foundation is growing that part of its programming so that knowledge of, and comfort with, science are improved and that the next generation of scientists will be more diverse. As part of those efforts, the foundation launched the online science publication Quanta Magazine, which just won a Pulitzer Prize, and Sandbox Films, whose Fire of Love was nominated for an Oscar this year.

Simons isn’t slowing down intellectually either. Whereas many mathematicians and scientists have a peak in their career, Simons has continued contributing to our understanding of the universe and its underlying rules for over half a century. Today, as co-chair of the board, he still monitors and helps guide the foundation’s scientific work. Jim and Marilyn Simons have also signed the Giving Pledge, meaning that eventually at least half of their accumulated wealth will be reinvested in science, undoubtedly, and in other philanthropic causes.

But most important to Simons is the message that scientific exploration, intellectual curiosity and trust in the power of math and science will ultimately prove our salvation. While the future is uncertain, the future will be one which Simons has helped shape, with his brilliance, resources and desire to see his diverse contributions benefit humanity. Now that’s a life that adds up perfectly.