Andy Warhol’s ‘Cars’ Exhibit Is An Arty Tribute To Mercedes-Benz

Warhol’s works honoring classic Mercedes-Benz models are on display alongside the real rides at L.A.’s Petersen Automotive Museum.

(© 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

August 6 would’ve been Andy Warhol’s 96th birthday—and even though the world lost the iconic progenitor of Pop Art in 1987, Warhol’s work still thrills.

On July 23, his final series was unveiled at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles for its first North American showcase since a 1988 debut at the Guggenheim in New York.

In fact, a lot of fine art sits hidden in storage of institutions or private collections—but that’s another matter. Now the Cars series reappeared, on loan from the Mercedes-Benz art collection in Germany.

Andy Warhol: Cars – Works from the Mercedes-Benz Art Collection presents the series in full alongside all eight Mercedes-Benz models it celebrates, courtesy of a curatorial collaboration between the Petersen and the collection.

|(Petersen Automotive Museum)

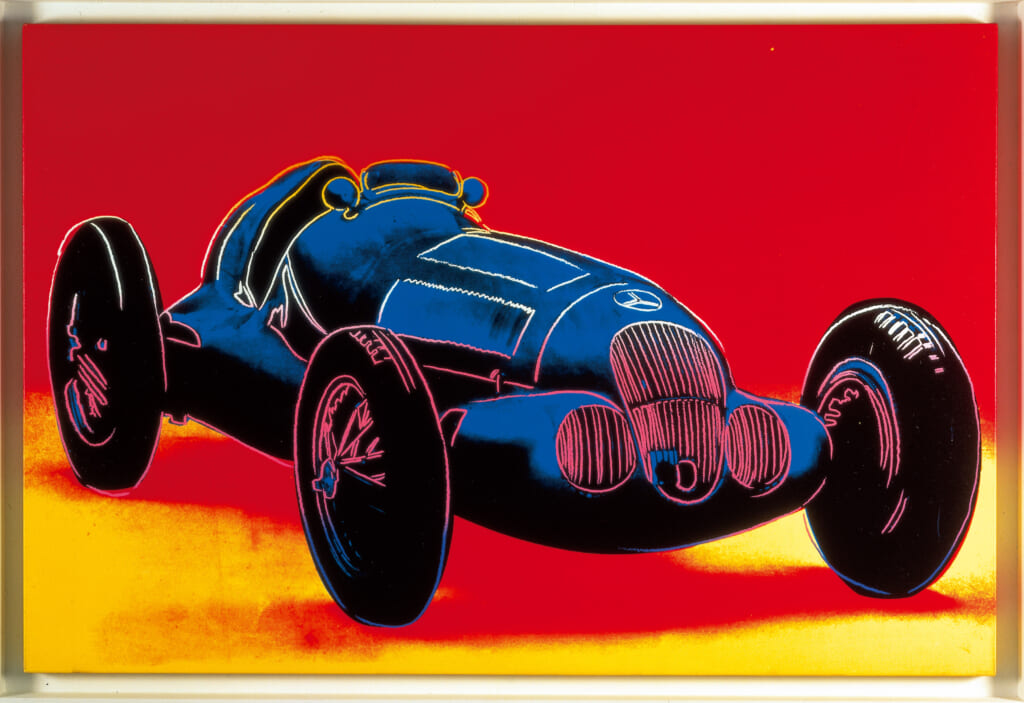

Warhol started the series in 1986, a commission from Mercedes-Benz to commemorate their 100th anniversary. This release says the company was inspired after “seeing Warhol’s silkscreen prints of its 300 SL Coupe”—arguably one of the greatest and most influential sports cars of all time.

“Warhol planned to create 80 pieces of art using 20 different Mercedes models spanning the German automaker’s 100-year history. But only 49 works—36 screen prints on canvas and 13 drawings—were completed before Warhol’s unexpected passing.”

Warhol had his own lifelong relationship with cars, buying his signature Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow upon achieving commercial success and keeping it forever. He never learned to drive and preferred to be chauffeured by Mick Jagger, Imelda Marcos, and Liza Minelli.

(Petersen Automotive Museum)

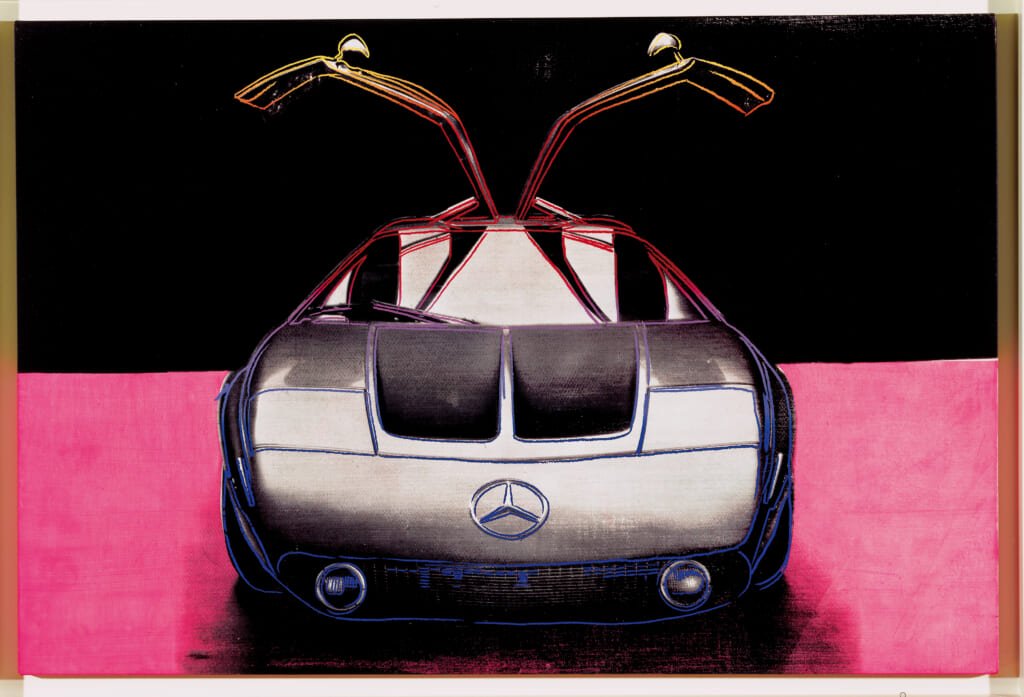

Exhibited at the Petersen in full, Warhol’s final series reinterprets motifs which made him famous in the first place—colorful silkscreen images of pop culture archetypes in varied hues, accented throughout with acrylic paint.

Still, the wall text notes that over eras, Mercedes-Benz has evaded the mundanity of the artist’s other subject matter—consumer goods like Campbell’s or Coca-Cola bottles (or Ruscha’s infatuation with Spam.)

“These vintage automobiles, like many exclusive luxury products, are desired by many but scarcely available to the masses,” wall text says.

(© Mercedes Benz AG)

Where else could you see Warhol alongside a 1937 W 125 and its 637-horsepower eight-cylinder engine, the most powerful Grand Prix racer for 30 strong? That’s from the Mercedes-Benz museum in Germany, but the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum chipped in for this show with a 1954 W196 Formula One racer, which “won two world championships before Mercedes pulled out of competitive racing for three decades,” per the release.

The 1886 Daimler Motor Coach looks like a contraption by comparison, but it makes for trippy artwork across the way, al tessellating angles and experimentation with lesser-known accents like geometric overlays.

The 1970 Type C 111 does look as silly front-on as Warhol’s depiction, but it’s also an angular marvel to experience. “Despite numerous ‘blank check’ orders received from the public, the C 111 remained an experimental vehicle and never entered series production,” accompanying information at the show says. What could’ve been.

(© 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Director of Exhibitions Bryan Stevens told Maxim that the Petersen inaugurated the Armand Hammer Foundation Gallery in 2015 with the specific intent to explore “the many relationships between cars and art in one space.” Just outside the Warhol exhibition was another exhibition in ode to automobiles, watercraft, motorcycles, and more from the cinematic James Bond saga.

Maybe we forget because they’re so ubiquitous, but cars are art. Each one starts as a drawing. “We take every possible opportunity to create exhibits that benefit from overlapping facets of human culture,” Stevens said. They find inspiration from architecture to fashion and gaming.

“Fortuitously, the exhibit may also benefit from a wave of renewed interest in Warhol following the recent high-profile sale of one of his works,” Stevens continued, referencing the May 9 auction of Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, which went for a $195 million and wrested the world record away from a blue Basquiat skull. A luxury good in her own right, Monroe evaded mundanity by passing away.

(© Mercedes Benz AG)

Los Angeles makes a fitting city for the series’ reappearance. The wall text for one of Warhol’s Campbell’s silkscreens on view at LACMA, just down Museum Row from the Petersen, says his soup cans debuted at Ferus Gallery in LA in 1962. LACMA’s edition “was commissioned by the Campbell’s Soup Company in 164 as a gift for their retiring board chairman.” That story echoes the origins of this Cars series—a recurring anecdote not only about how art circulates, but how it gets made.

Automobiles are greater than what we make them out to be—that’s clear at the Petersen, the interplay between awe-inspiring machines and their visual art counterparts. Aerodynamics makes negative space positive—cars are designed to work with motion and air, unseen forces made real. They’re what the wind looks like in reverse. That foundational beauty is everlasting.

“Many Mercedes-Benz models are considered icons of automotive design and are widely admired for their timeless elegance and purposeful, rational aesthetic,” Stevens said, citing the 300SL in particular. “However, they are especially compelling as the subject matter for an artwork series for another reason: the cars of no other car company could be used to illustrate the entirety of the history of the practical automobile.”

(Petersen Automotive Museum)

Catch the Petersen’s original Warhol x Benz collab while you can.