How Enzo Ferrari Created The World’s Most Iconic Supercar Brand

“Think as a winner and act as a winner, you’ll be quite likely to achieve your goal.”

The bust of one Enzo Ferrari rests on the Mount Rushmore of the automotive industry, eyes forever hidden behind thick blocky sunglasses. Carved stoically next to perhaps Henry Ford, Gottlieb Daimler and Ferdinand Porsche, all staring off into the horizon. Referred to as “il Commendatore” by those who trembled at his approach, or “il Drake” for the many who envied him, and “The Pope of the North” by the army of admirers. Libraries of books, documentaries and films have tried to capture the enigmatic aura of the man who changed the automotive landscape in ways few, if any, have. We’ll do our best to sketch an outline.

On February 18, 1898, in the small city of Modena just before the dawning of the 20th century, Enzo Anselmo Giuseppe Maria Ferrari was born. The family lived simply but happily above his father Alfredo’s metal workshop where he manufactured parts for the rail industry, while Enzo nurtured nascent interests in singing (as a tenor in opera) and sports journalism (He published his first article about an Inter Milan victory in the largest Italian sports newspaper at the ripe age of nine.)

That is until 1908, when his father took him and his brother Alfredo Jr., nicknamed Dino, to the nearby Circuito di Bologna to witness firsthand the legendary racer Felice Nazzaro score the checkered flag in a blur of clay dust and choking exhaust. An obsession blossomed right there and then that would, in the coming decades, figuratively and literally set the world on fire.

But his family would first have to deal with twin tragedies as the Great War swiftly ravaged the continent. In 1916 both his father and brother died, the latter succumbing to the Italian flu pandemic, razing their business and casting their family into desolation. The following year a young Enzo enlisted in the 3rd Mountain Artillery Regiment and shipped north.

There he fell ill as well, which had the fortune of pulling him from the front lines. Despite the precarious post-war economic climate Enzo gambled on his obsessions. During the burgeoning dawn of the automobile, one couldn’t break into the clandestine and insular racing tribe without their own ride; you could barely even hang out at the racers’ bar without your own keys. Enzo knew he had to cleverly maneuver his way into this nascent world of speed and motorsport.

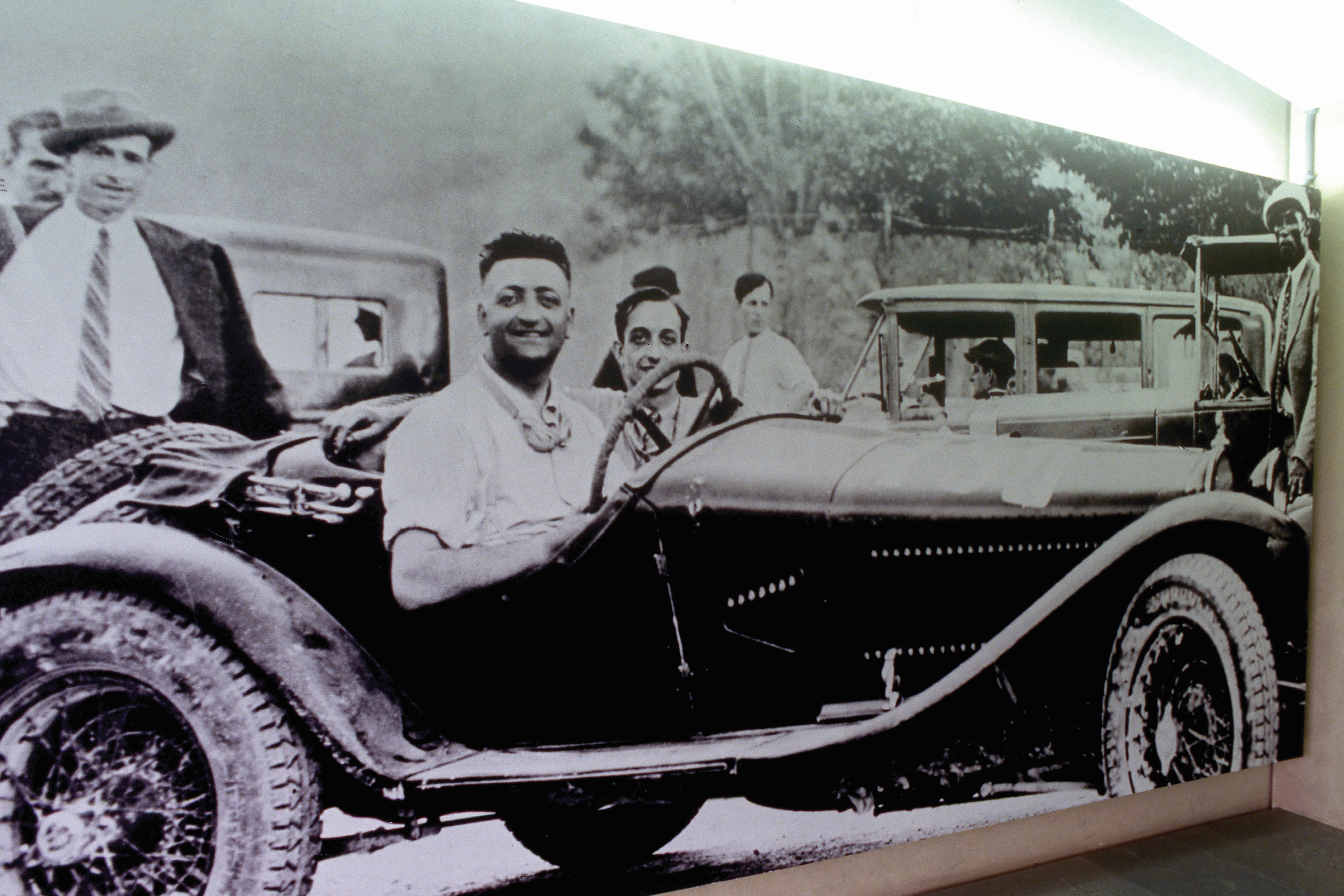

So he moved to Turin to earn employment with Fiat, but when that failed, turned to startup Italian automotive firm CMN. His early politicking skills helped Enzo convince CMN to sell him a car to race with, and at his first competition, driving a 2.3-liter 4-cylinder CMN 15/20, the young driver notched an impressive fourth place at the 1919 Parma-Poggio di Berceto hill climb.

Only a year later Enzo piloted a 6-liter Alfa Romeo 40/60 to a surprising second place finish at the Targa Florio. A critical relationship with Alfa Romeo, at the time a motorsport powerhouse, cemented. The following year at the Brescia GP Enzo scored another second place finish. At his maiden Grand Prix at the Savio Circuit in Ravenna in 1923, Enzo won.

Despite winning three more races in 1924, signs were already materializing that his career as a driver might have its limitations. While slotted to drive in the French Grand Prix in Lyon, Enzo mysteriously dropped out at the last minute, without explanation. Some speculate the fear that’s aborted oh-so-many promising racing careers had begun creeping in.

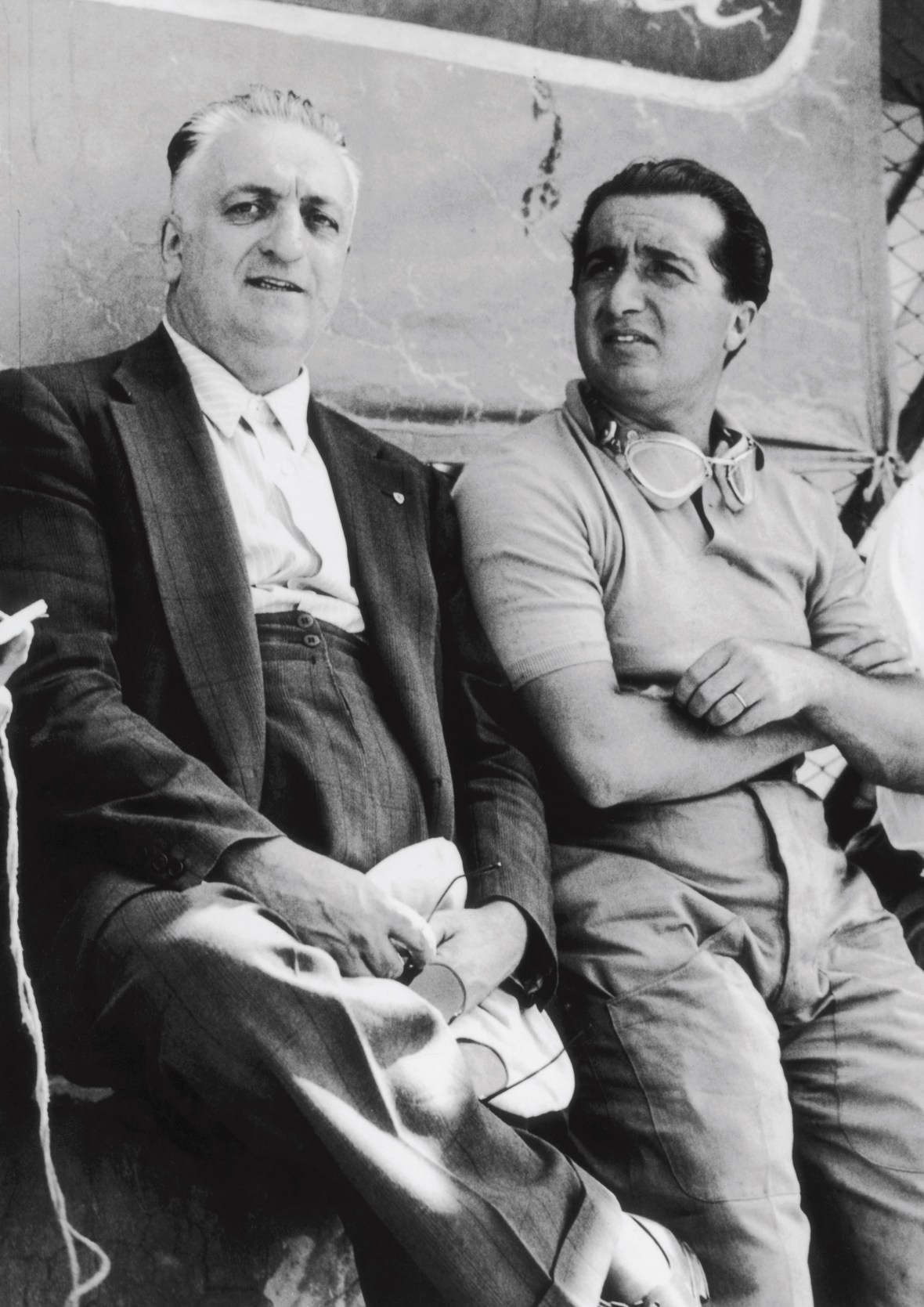

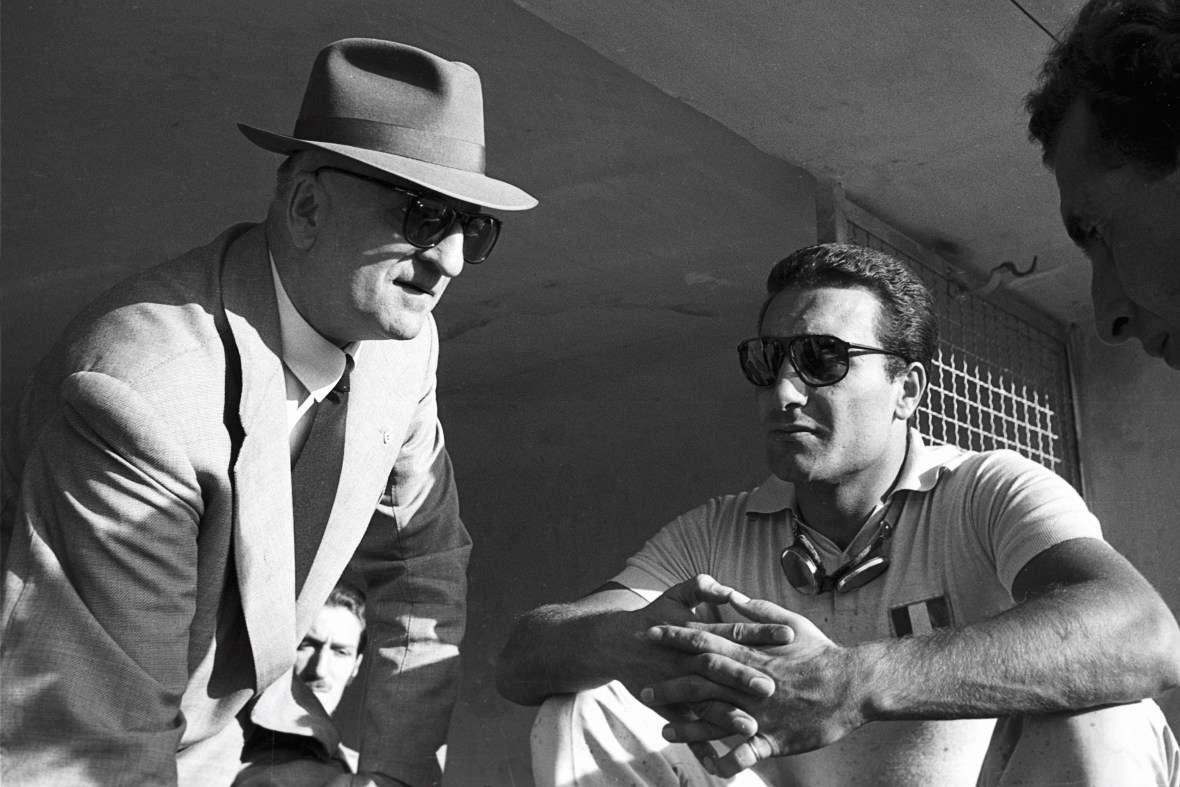

Not coincidentally around this time Enzo’s ambitions started growing beyond simply driving. In 1929 he founded his own racing team under the “Scuderia Ferrari” moniker, convinced Alfa Romeo to effectively lead all racing activities, and won 8 of its 22 races. This is yet another example of perhaps Enzo’s greatest talent: charm. Manipulation. Working the angles. However you want to put it, biographers, friends, enemies, admirers and nemeses all point out the ceaselessly ambitious and calculating Italian’s ability to bend situations to his whim; a Jedi of psyche.

“If Ferrari had been in politics,” his friend and longtime Ferrari accountant Carlo Benzi has been quoted as saying, “Machiavelli would have been his servant.” As a symbol of his new stable at Alfa Romeo, Enzo selected a black horse dancing on a shield and began using it on all his cars starting with the 24 Hours of Spa in 1932.

Although some details are lost in the fog of time, we do know Enzo met the Countess Paolina Baracca di Lugo when he won at the Circuito del Savio for the second time in 1924. Legend has it when she handed him the winner’s cup she also gifted him a necklace with the Prancing Horse symbol painted on the plane’s fuselage of her son— the decorated fighter pilot Francesco Baracca—saying it would bring him luck, and the iconic Ferrari badge was born.

While a capable racer in his heyday, by the time he retired in 1932 Enzo looked on at contemporary Tazio Nuvolari with both envy and awe. Still referred to today as amongst the best drivers ever, Nuvolari was so fast and fearless they whispered he’d made a deal with the devil. In Nuvolari Enzo saw not a rival, but an ideal: the archetype against which every driver would be compared.

In 1931 he finally convinced Nuvolari to jump ship and join his Scuderia—perfectly timed to pair him with one of Alfa Romeo’s greatest achievements in racing: the 150-plus-mph P3. Together they dominated the sport until the mid ‘30s, when major global socio-political shifts began changing the European racing landscape. The fascists saw motorsports as another potential avenue to prove German superiority, so they began pouring money and brainpower into the teams of Mercedes-Benz and Ferdinand Porsche’s Auto Union, the precursor to today’s Audi.

Ferrari dominated Formula One in an era where it commanded a global level of awe matched only by the astronauts of their age.

The positives being automotive engineering milestones like technologically advanced double wishbone suspension with coil springs, advanced brakes and eventually moving the engine behind the driver for superior physics. The negatives being these small teams could never compete against the nationally subsidized ones. Suddenly Enzo’s P3 fell from dominance to obsolescence seemingly overnight.

Until the 1935 German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring. Despite driving a vastly inferior car and suffering mechanical failures, Nuvolari managed to outduel Manfred von Brauchitsch and the German technological superiority of his famed Silver Arrow while Enzo watched in awe.

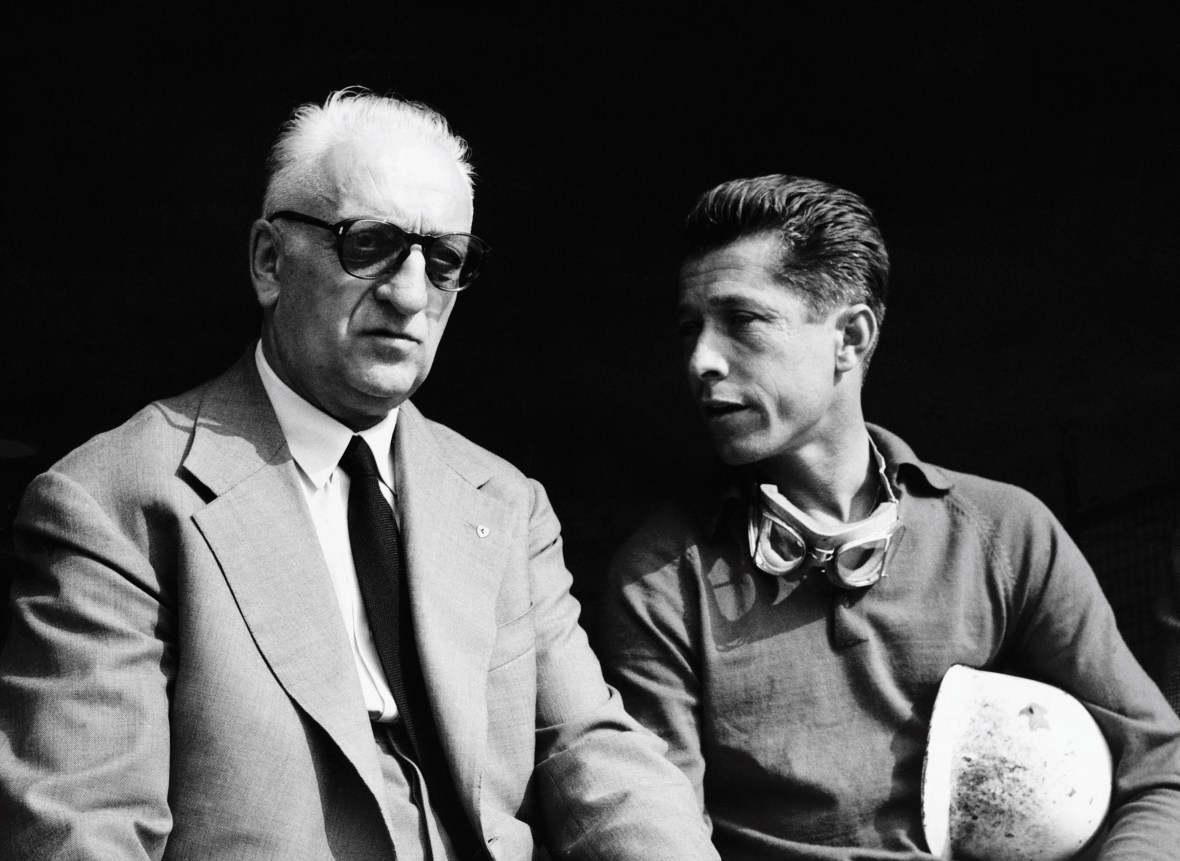

Biographers credit this race with creating in Enzo’s mind the model of the perfect driver, one with which all future Ferrari drivers would forever be compared. Much to many the chagrin of many of his future drivers—legends such as Juan Manuel Fangio, Niki Lauda, Alberto Ascari, Gilles Villeneuve and Nigel Mansell—Nuvolari had unwittingly seared almost impossible expectations into the mind of the young team manager.

Despite his victory and Enzo’s gushing admiration, Nuvolari switched sides the following season and joined the powerful Mercedes team. Alfa Romeo fired Enzo, and to make matters infinitely worse the dark storm of WWII swept across Europe.

He established the Auto Avio Costruzioni firm to machine aeronautical parts for the Italian war effort, but also leveraged the opportunity to build his first car: the AAC Tipo 815 (Due to a clause in his Alfa Romeo contract, Enzo could not use the Ferrari name in any automotive endeavor.)

Despite promising starts to their only race at the 1940 Brescia Grand Prix, both units retired due to mechanical troubles. Soon the climaxing war slammed the brakes on all motorsports, but this forced sabbatical as a manufacturer began turning the gears of entrepreneurship in Enzo’s mind.

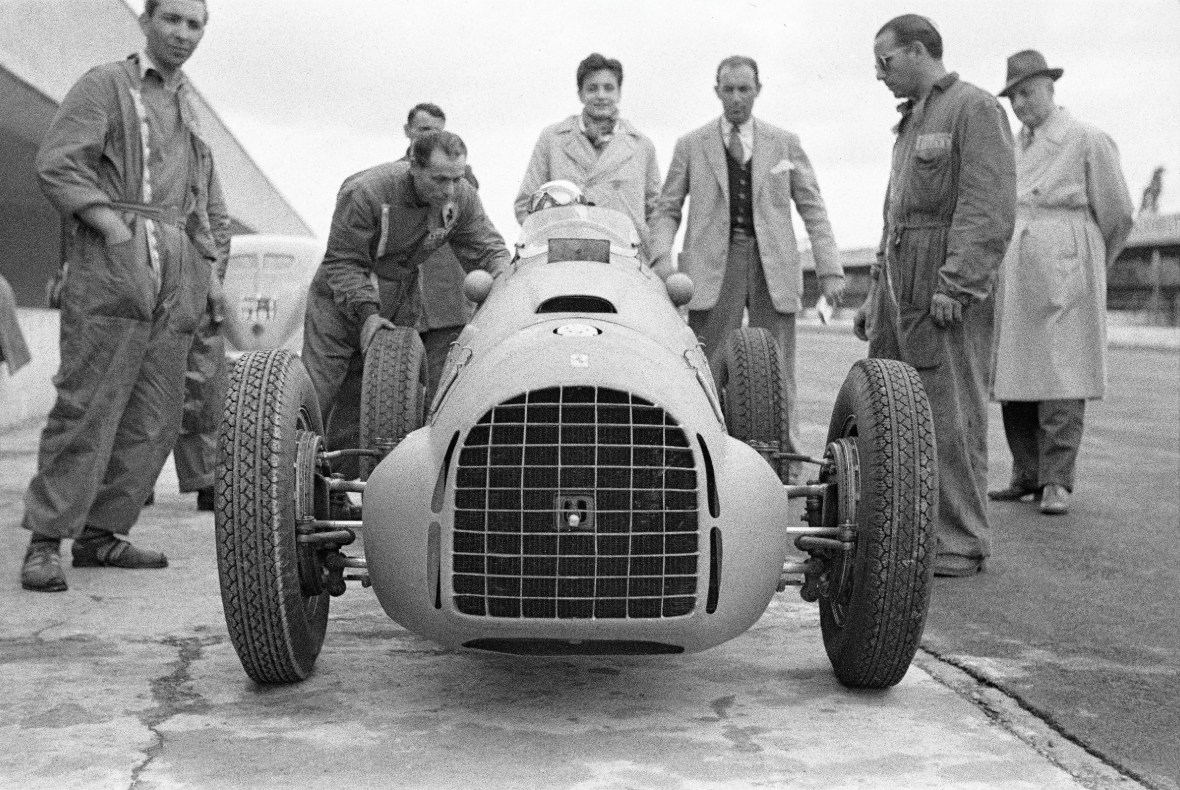

So he bought a cheap tract of land just outside Modena in Maranello in 1942. Despite his factory being bombed twice, Enzo emerged from WWII with two pieces of good news: first the birth of Piero, his son by Lina Lardi. Then in 1947, at the tender age of 49, the establishment of the Ferrari marque with his first racecar: the 12-cylinder Ferrari 125 S.

By the end of the decade Ferrari was dominating motorsport from his headquarters, consistently beating his old Milan employer and winning 32 out of 49 races in 1949. This kicked off a decade of hegemony, highlighted by an unseen four Gran Prix World Championships. Some argue this was the golden era of motorsport, the halcyon years of limitless swagger, passion, danger, adventure and desire.

The days when Formula One was considered the most glamorous sport on earth, the paddock filled with beautiful women and men swigging whiskey shots before races, staring death in the eye as they strapped on a helmet. Ferrari dominated the sport in an era where it commanded a global level of awe matched only by the astronauts of their age.

Right from the outset Enzo recognized a necessary income stream for Ferrari: building roadgoing versions of his globally renowned racecars for “gentlemen drivers.” The first being the V-12-powered Ferrari 166 Inter in 1948.

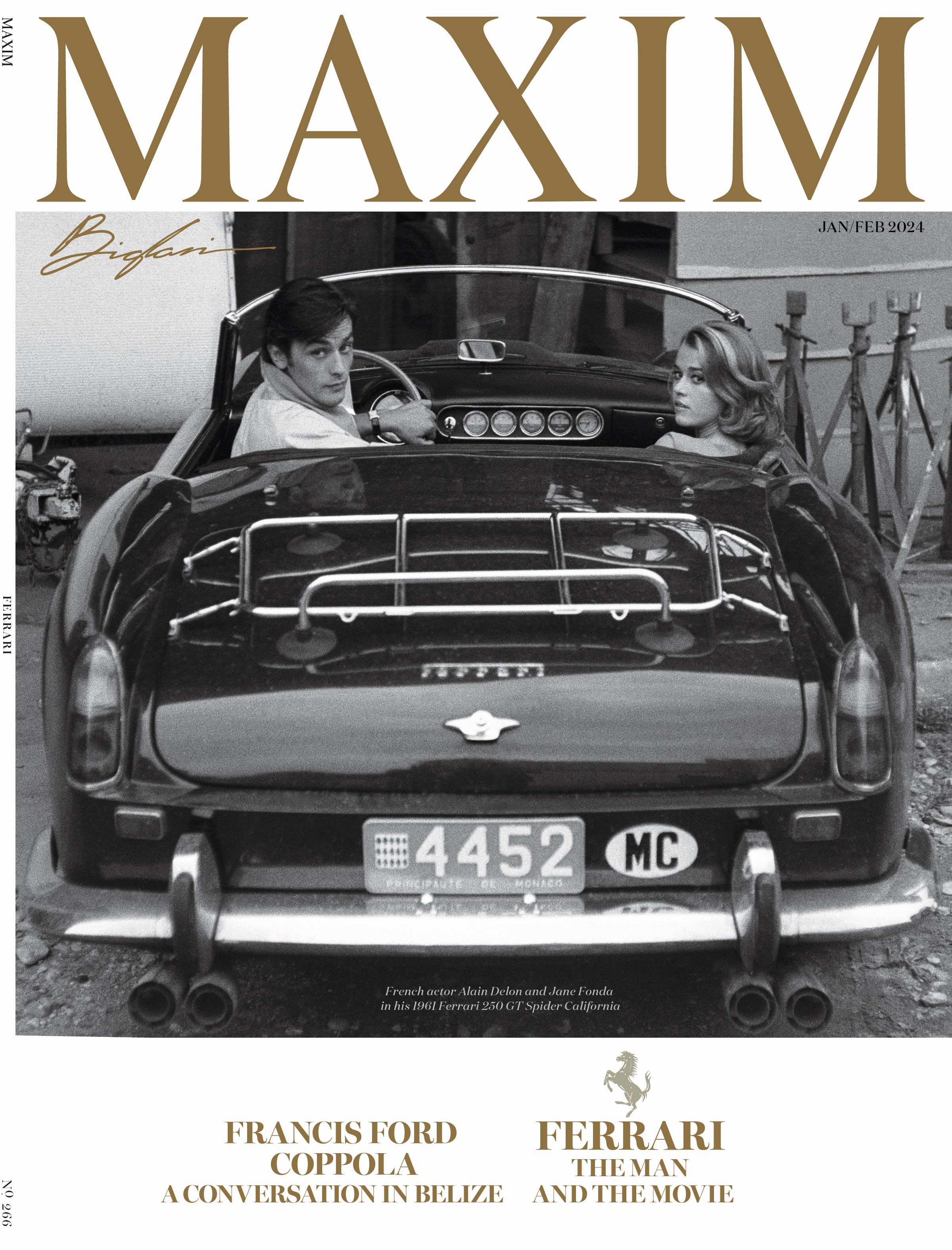

Almost immediately movie stars like Steve McQueen, Elvis Presley and James Coburn began leveraging their charm to have their dream vehicles delivered faster. The cars appeared in paparazzi pulp papers revealing Ingrid Bergman cozying up with Roberto Rossellini, and then began popping up in films like The Thomas Crown Affair, Viva Las Vegas and The Long Goodbye—at times outshining their illustrious co-stars.

By the 1980s Sonny Crocket’s 365 GTS/4 Daytona Spider and then-blizzard white Testarossa were staples of Miami Vice, Magnum’s 308 GTS became as iconic as the mustached PI’s short-shorts and Hawaiian shirts, and the 250 GT California Spider played vehicular McGuffin for Ferris Bueller’s famed day of playing hooky.

The Testarossa seemed particularly destined for fame, its super sleek profile and bombastic side strakes soon invading bedroom posters and arcade screens in the wildly popular Out Run video game. But it’s critical to note these roadgoing cars were only an ends to a means.

Enzo established the winningest team in F1 history, capturing over 5,000 checkered flags across the globe.

Enzo himself never really cared for that side of the business, seeing it as a necessary revenue stream to fund his motorsports efforts. Appropriately Enzo Ferrari eventually established the winningest team in Formula One history, capturing over 5,000 checkered flags across the globe—and to this day remains at the sports apex.

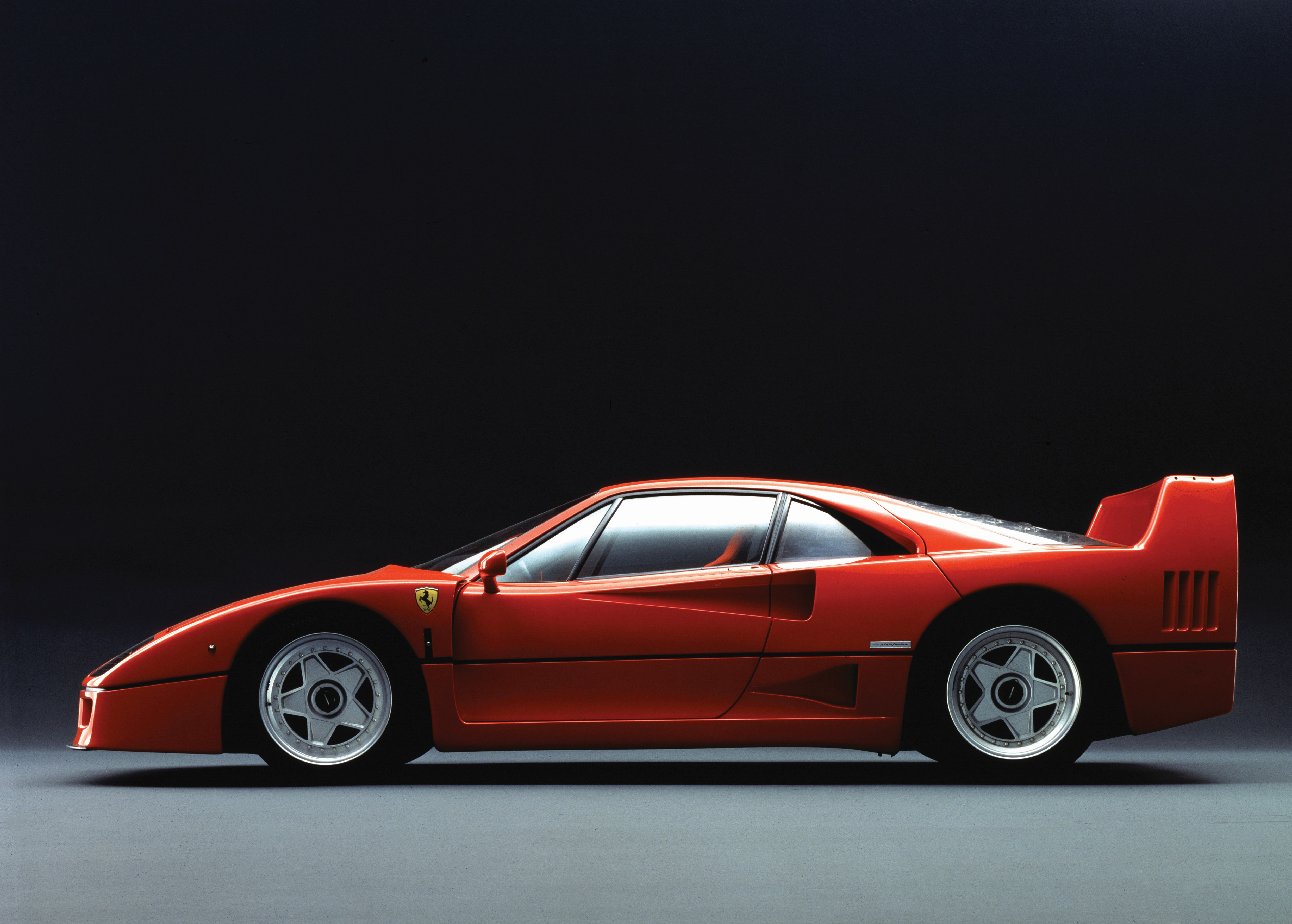

Fittingly the last Ferrari street car engineered and built under his stewardship was the sui generis F40. The first car in history to eclipse the 200-mph barrier, constructed of futuristic materials like Kevlar, carbon fiber and aluminum.

With his swan song Enzo didn’t just cement a legendary marque, he ushered in the age of the supercar. During his lifetime the Pope of the North forged the crucible of motorsports, sowing the Italian landscape with seeds of pride, performance and victory. He also transformed a provincial region best known for prosciutto, parmigiano reggiano cheese and Sangiovese wine into an automotive and technology powerhouse distinguished across the planet.

“The best win is the next,” Enzo was known to repeat as mantra. “Think as a winner and act as a winner, you’ll be quite likely to achieve your goal.”

Follow Deputy Editor Nicolas Stecher on Instagram at @nickstecher and @boozeoftheday.

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2024 issue of Maxim magazine.