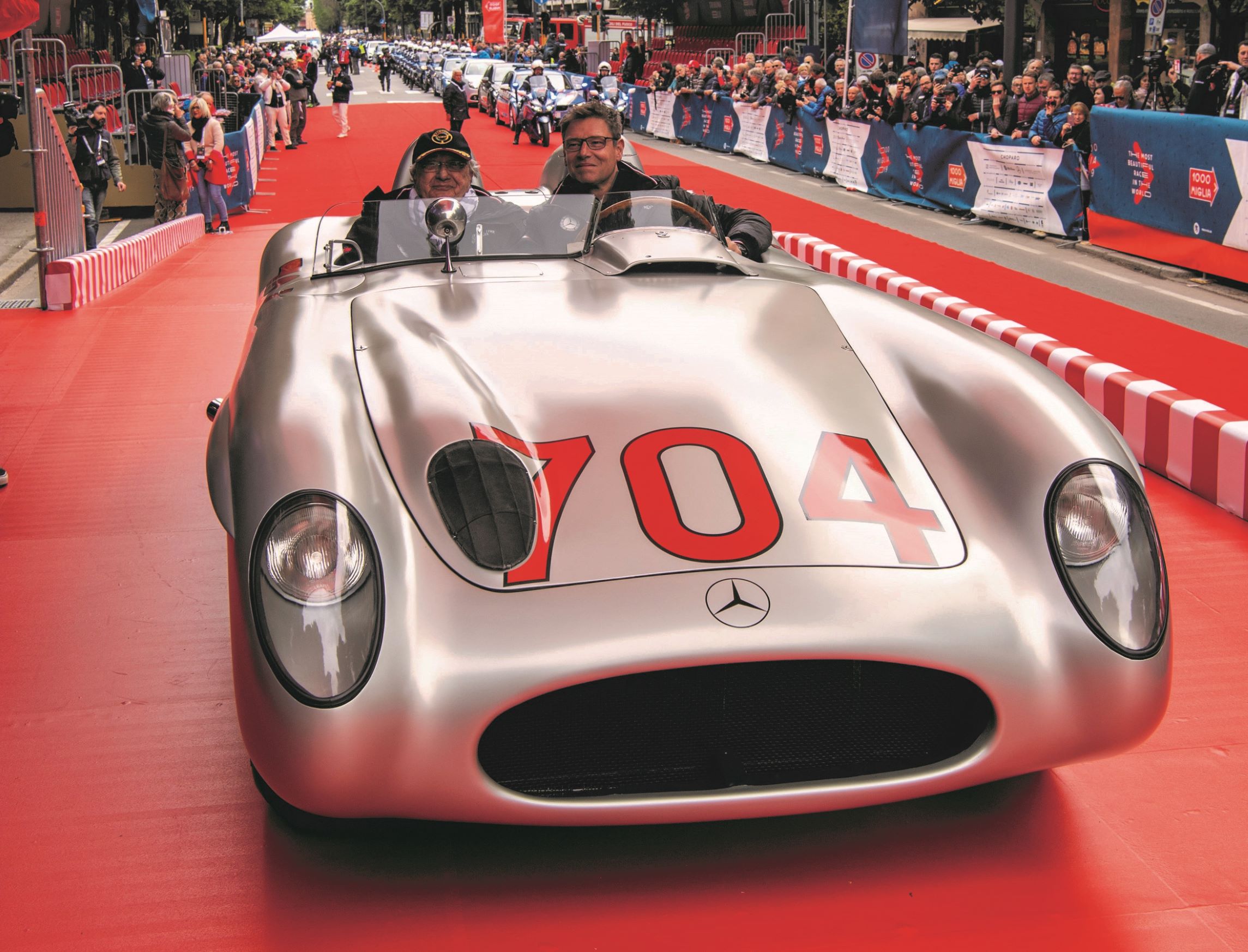

We Raced a $2 Million Mercedes-Benz Gullwing in Italy’s Legendary Miglia Rally

Four days and 1,000 miles of breaking nearly every driving law known to man in multimillion-dollar classic cars.

The first time I fire up the 300 SL my stomach is in knots. I’m in a parade of 400-plus cars charging their way out of the Italian city of Brescia, but this is no ordinary procession. This is the famed 1,000 Miglia (“Mille Miglia”), arguably the most legendary rally the world over, meaning each of these antique vehicles is a collectable widget of obscene value.

There are Bugatti Type 35s, Ferrari 750 Monzas and Blower Bentleys in our midst. The entire scene feels strangely apocalyptic—a high-tension dip and duck through teeming public roads with police motorcycles zipping by, sirens blaring their binary wail, stopping traffic at every intersection so this parade can snoot by in a display of surreal entitlement.

Maybe it’s my nerves, maybe it’s the $2 million street value of this 1956 Mercedes-Benz 300 SL “Gullwing” (spec’d as a ’55) I’m piloting white-knuckled, or maybe it’s the flashing lights, alarms and high-revving Ducatis ripping by from every direction, but the whole scene has a distinct Children Of Men anxiety to it. It is, in a word, chaos.

The first time you slip behind the wheel of a priceless unicorn, all you can think about is pressing the throttle at the right time, not burning the clutch, and navigating the four-speed stick without grinding gears. You don’t want to think about the absolute impotence of its prehistoric drum brakes and their inability to spare the six-decade-old car from a wall—never mind a distracted Fiat Panda—if it all goes sideways.

And you definitely don’t want to think about the seatbelts, or rather the fact the car has none. You just focus on the throng of Italians swarming ahead, clapping and cheering enthusiastically, totally and utterly oblivious to how difficult it is to feather the brakes and keep them safe.

But soon we escape the hell of the city and slip into the open Italian landscape, releasing a deep sigh of relief. This is where all becomes right in the world. When the Mille Miglia exposes its furry belly for a friendly rub. It’s also where the velocity begins.

The first run of sweet freedom brings to mind a term famed automotive journalist Denis Jenkinson used: “dice”. As in: “If we didn’t press on straight away there was a good chance of the dice becoming a little exciting, not to say dangerous, in the opening 200 miles.”

He wrote that in 1955 of his second time competing in the Mille Miglia, the year he and driver Stirling Moss would win the race in a Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR in just 10 hours, 7 minutes and 48 seconds. It was the fastest time ever recorded in the contest—a record that remains unbroken to this day. And while we’ll never come close to his speeds, in our first burst of combustion and mechanical havoc outside Brescia I feel the tension Jenkinson referred to vibrating in my bones.

The Mille Miglia, first raced in 1927, was conceived by a group of Italian counts and gentlemen eager to elevate Brescia’s motorsports profile. The loop was to begin and end in Brescia, hitting Rome and Bologna along the way: roughly 1,000 blistering miles through closed public roads at speeds eventually reaching 170 mph by 1955. The Mille Miglia took a six-year break during the madness of World War II, re-started, and then shut down forever as a purely speed-focused race in 1957 after a tragic crash, the most significant accident in its history. While fatalities were not uncommon, public perception finally shifted when a tire on Alfonso de Portago’s Ferrari 335 S blew out, sending the car catapulting into the crowd, killing him, his copilot and nine spectators.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B45bCTvldmh

To honor the Mille Miglia’s epic status in motorsports, the race was resurrected in 1977 as a more traditional rally, meaning the first across the finish line isn’t necessarily the winner. Only models that completed registration for the original races are eligible to compete. At its most basic, the event is an eye-watering journey through one of the most gorgeous landscapes on Earth. Many choose to putter along in prewar Lancia Lambdas simply enjoying the route, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Most, however, opt to lean into its feral nature, racing vehicles whose auction prices soar well into the millions at speeds no vehicle without ABS should be driving.

These are the streets where gladiators like Fangio, Castellotti and Taruffi barreled through at unthinkable speeds, hitting corners blind except on faith of memory. You drive over cobblestone streets into walled fortresses, through tiny ancient piazzas. Vineyards and twisted olive groves soaking in the sun. Across rivers, past brick towers, cathedrals and vast domes plucked from Game of Thrones. The Mille Miglia leads you through breathtaking old villages that even as a seasoned traveler you’ve unlikely heard of. Roverbella, Mantua, Laggo di Mezzo.

And the entire nation of Italy is behind you. Never mind the legions of roadside fans, the police escorts might just be the most insane aspect of the entire Mille Miglia. Carabinieri not only wait at crowded intersections to block off plebes and wave you by, but every once in a while a motorcycle cop will pass you, sirens blaring, and start parting rush hour traffic like Moses and the Red Sea. It never feels normal; you slow down because you assume you’re the mark, then you realize it’s your duty to follow him as if you were the Pope late for eucharist. Maybe some of the billionaires on the Mille have experienced this level of privilege before, but to a normal human it feels like you’ve fallen into a video game on cheat mode.

And all the while, at every stop, Italians gleefully wave tricolor flags. Happy hour celebrators sit at cafés and cheer. You’ll turn a corner in the middle of nowhere and a line of tables appears loaded with impeccably dressed nonni drinking tall glasses of Campari, watching a half-billion dollars worth of cars parade by. It is all effortlessly cool, and eminently Italian.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BxqNcb8FkqN

Many consider the 300 SL the world’s first supercar. Although some debate this mantle, a streetlegal supercar does its talking at the track and the 300 SL was unparalleled in its era. On the same year of the Mille when Moss made his record-breaking run in the 300 SLR race car, American racing legend John Fitch piloted his 300 SL to a class win, and fifth overall. And the car we’re driving courtesy of the Mercedes-Benz Museum is nearly identical, from the tuning to the slate grey paint with Fitch’s number 417 across the hood. 300SLs went on to claim first and second at Le Mans, and then sweep the podium at the Nürburgring.

Mercedes’s proto-supercar featured direct fuel injection, the first production car ever to implement this next-level technology. A limited number were also built with aluminum bodies. But as game-changing as all those advancements were, they weren’t the 300 SL’s most salient innovation; that would be its welded space-frame chassis.

The unique tubular-steel construction was implemented so the SL (SportlichLeicht, or “sport lightweight”) could earn its moniker‚ and to make it work, engineers and designers had to invent a new form that avoided cutting too deeply into the doorsill. The resulting “gullwing” doors were as revolutionary from an engineering standpoint as from an aesthetic one, and elevated the 300 SL to otherworldly heights. If its 161-mph top speed, superlative 215 horsepower 3.0-liter inline six and extreme aerodynamic efficiency didn’t make this the world’s first supercar, then those outstretched doors looking like a soaring bird of prey surely did.

And what better way to highlight the Gullwing’s midcentury hegemony than by letting a journalist who was born a couple decades later slip behind the wheel? Because simply driving the Gullwing would only give you a vague idea of its superiority; one would only compare it to modern machines. But to have the opportunity to roll Jenkinson’s dice with the 300 SL versus its contemporaries—and experience it chewing and spitting them out in big mushy chunks—is another lesson altogether. And oh lordy the sound; what I imagine strafing enemy aircraft in some forgotten African skirmish might sound like. Floor it, and deeply mechanical, rapid-fire combustions echo across the Tuscan hills.

“What a thing,” my copilot Kyle Fortune, the excellent Scottish motoring journalist, sighed wistfully after an especially intoxicating thunder through dark forests. Of course the Gullwing is beautiful; saying so seems mind-numbingly obvious. It’s one of the most iconic cars of all time. But you don’t think about its beauty in the heat of high-pressure racing; you only obsess over the safety of nearby pedestrians, keeping the car unblemished, and your own health—in that order.

When you have a moment to reflect, however, its radiance sharpens in focus. Driving behind one of these machines you ponder the trees mirroring off of the pristine paint, their silhouettes curving around its divine haunches. Rarely has a German vehicle been this voluptuous. No wonder the locals famously love the 300 SL; it’s almost more Italian in its sensuous Zagato-like curves and soft rounded edges then it is Teutonic. More emotion than logic in shape, even if all the mechanical wizardry under the skin was unparalleled for its era.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B45bqWFFiVc

One of the banes of the Mille is the official support vehicles with which you must sometimes share the road. Unlike civilians who normally move over to allow safe passage, these drivers often accelerate as if they were competing against you. Considering they’re in modern Alfa Romeos and Porsches this can get highly frustrating, and even dangerous. It is during yet another bout with one of these support Giulias that a straight appears, an empty passing lane not unlike one we’ve seen a thousand times before.

My copilot moves left and pushes the throttle. Predictably the Giulia speeds up in response to block us. Seeing clear road we accelerate more to overtake. Suddenly, rising from a dip no one saw, a Renault Mégane materializes out of nowhere maybe 100 yards ahead on the horizon.

My heart stops. At that moment I realize I am no poet, as the only thing to escape my lips is the blurt of a simpleton: “Oh. No.” Funny how you don’t know yourself, truly know yourself, until you’re staring death in the face. Oh. No. The same thing you might say when your favorite café informs you they’ve stopped serving breakfast.

Luckily, Fortune is on top of it. He stomps the throttle; we’re way past the point of no return and braking would only guarantee a head-on collision. With an explosion of the inline-six, the 300 SL shoots forward and tucks in just ahead of the Alfa Romeo as the oncoming Mégane whizzes past honking frantically, mere inches to our left.

Luckily we avoided the Renault; unluckily the road immediately bends left, so now we’re headed straight for a guardrail at an absurd velocity. Releasing the throttle loads up the front axle, and Fortune jerks the wheel left. The combination of pure speed, violent direction change, sudden road dip (that which hid the Renault) and the 300 SL’s rear swing-axle soon has the car’s ass swaying out in oversteer.

The Gullwing skids on the ropes, and us along with it.

In that instant I realize there are two, and only two, options: Fortune would have the skills to recover the coupe—a car with no stability or traction control, ABS, or, may I remind you, seatbelts—or we’d slingshot at ridiculous speeds off the road into a ditch for an explosive De Portago finale. For a moment everything stands still as I contemplate these possibilities. Sadly, quite selfishly, I don’t think about the girl I love, or my parents, or anything outside of myself really. I just sit there gripping the door, watching Jenkinson’s famed dice bounce, the rear wheels bouncing along with them. Right to left to right to left again, our collective fate tumbling alongside them. Light or darkness. Lucky sevens or snake-eyes. Life or death.

A millennia— or maybe three seconds—later, the Benz urgently finds its footing and we shoot forward in a straight trajectory, once again zooming up the Italian roadside as if nothing had happened. I look over at Fortune, my once-paused heart suddenly exploding like an M-80, and I grab him by the shoulder. “Holy fucking shit man—nice recovery!”

Fortune looks forward sheepishly, his grey, bloodless visage washing over with a unique combination of shame and pride. And perhaps more than anything, relief. “Oh my god… I can’t believe you saved us!” I stammer once again. We both just look forward in silence, contemplating our mortality for 30 minutes. We would discuss that moment again later in the afternoon, and countless more times in our following days together. But for the next half-hour we utter not a peep, staring straight into the windshield, the only sound the euphonic braaaaaap! of the in-line six filling the cabin and rinsing our terror.