Here’s Why the Porsche 356 Is Still a Stone-Cold Classic

Porsche’s first production model has an amazing legacy.

Outlaw. It was meant as a joking epithet by Rod Emory’s friends, imagining the horror of Porsche purists at what they saw as Emory’s uncouth modifications to the precious Porsche 356. He embraced the diss, branding his custom vintage Porsche the 356 Outlaw and spawning a widely used, all-encompassing term that’s now applied to any classic Porsche modified from the way it left Stuttgart decades ago.

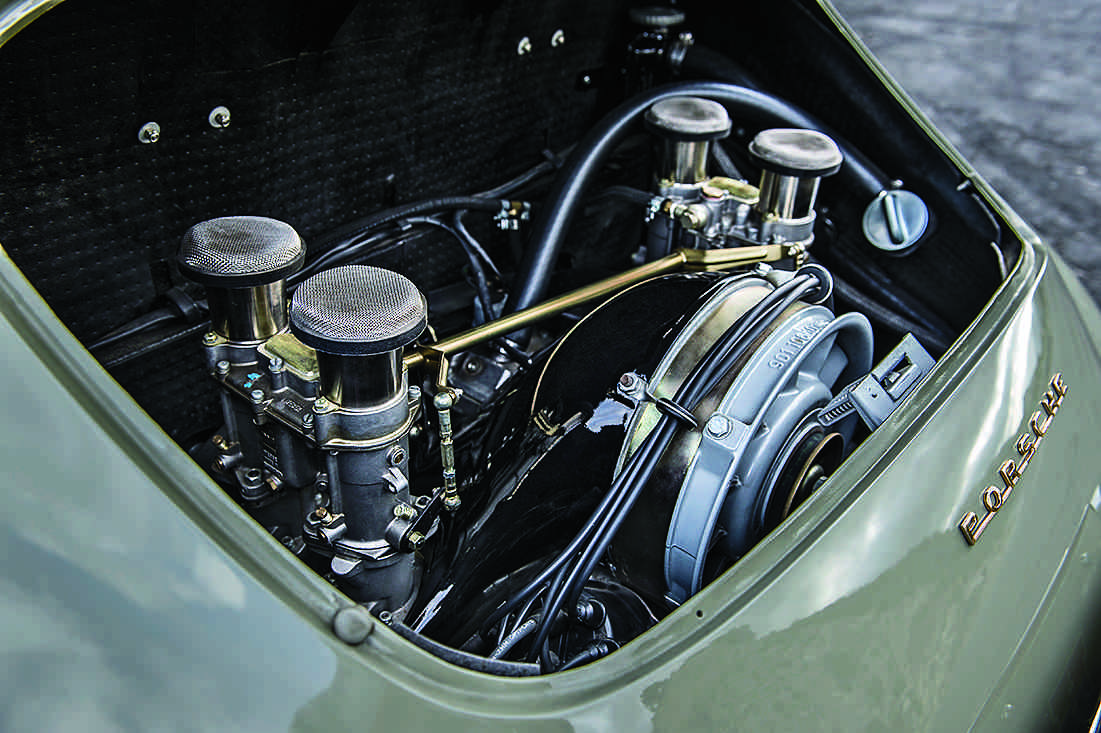

The 356 was Porsche’s first production model, and it shared many of the design themes founder Ferdinand Porsche used on the Volkswagen Beetle, including a rear-mounted engine derived from the Bug’s air-cooled four-cylinder power plant. This left ample opportunity for Emory to make improvements in the car’s performance and appearance.

Between 1948 and 1965, Porsche built 77,361 units of its pioneering sports car, a machine that established lightness and responsiveness as Porsche hallmarks. The 356 frequently defeated bigger, more powerful cars on racetracks worldwide. It was hot enough to attract the attention of Steve McQueen, who bought an open-top 356 Speedster in 1958. The Porsche was McQueen’s first racecar, and though it briefly passed into the hands of a classic car collector, McQueen bought it back in 1974, and it still belongs to his son, Chad.

Emory Motorsports officially opened its doors in 1996, though Emory himself had already spent a few years customizing Porsches for clients before formally making it his business. The restomodder’s car-customizing roots run deep, as does his connection with Porsche.

Neil Emory, Rod’s grandfather, opened Valley Custom Shop in Burbank in 1948, where he specialized in slicing porky Detroit iron into sleeker styles that pleased his eye, before moving on to work on Porsches and Volkswagens in 1962. Neil’s son, Gary, lusted after a Meyers Manx fiberglass-body dune buggy, but what he had was a crashed Volkswagen Beetle. With a bit of Neil’s help chopping and modifying, what might have been the first high-riding, knobby-tired, off-road-style “Baja Bug” was born.

After starting out at the same Porsche shop as Neil, Gary launched his own business, Porsche Parts Obsolete, specializing in selling parts for classic Porsches. This gave Rod Emory the chance to learn metalwork from his grandfather and the catalog of Porsche’s historical parts from his father. By the late ’80s, Porsche 356s from the 1950s and early ’60s were revered classics, but they weren’t excessively expensive yet, so he was able to obtain one and immediately modified it to suit his tastes, reshaping sheet metal and bolting on parts from Porsches of other vintages.

Pedigreed Porsche-philes were aghast at Emory’s irreverence, accusing him of ruining the car and leading to the “outlaw” appellation he embraces. Today, some of those purists seem to be on board, given that the Porsche 356 Registry has even created an Outlaw class for its car shows.

Two years ago, Emory Motorsports relocated from its base in Oregon to North Hollywood, only two miles from where Neil Emory’s old Valley Custom Shop sat. The higher-profile location has bolstered Emory’s reputation; in August 2015 he was featured on Jay Leno’s Garage.

What’s so special about the cars Emory builds? Only two things: their outside and their inside.

Outside, Emory Motorsports massages the cars’ lines just as Neil did for American hot rods decades ago, in some cases actually using Neil’s old tools to do the work. The object is to refine and customize the cars’ appearance, without changing their gestalt.

Among Emory’s signature modifications are fog lights, a gas filler cap that protrudes through the center of the hood, and leather straps that secure the hood. These cues appeared on racing cars of the 356’s era, and Emory likes to apply them to his Outlaws today.

Emory says it’s his aim to produce a car that looks better than it did originally, but that is changed so subtly that observers are hard-pressed to identify the alterations. He achieves this by doing things like snugging the bumpers right up close to the body rather than leaving them jutting out far from the sheet metal.

“It’s really about making subtle changes that are hard to pick up on, and making it look like it was supposed to be that way,” Emory says.

Inside, he exploits Porsche’s penchant for continuity, which means that some parts from the very newest models are still similar to those on the old cars, making them adaptable to Emory’s classics. This has meant that engine parts from the 1990s and suspension parts from the 1980s can be repurposed to make ancient cars drive with a little more precision.

Over the years Emory Motorsports has rebuilt more than 150 cars. About 80 percent of them have been his signature 356s, though there have been other Porsche models, too, as well as some VWs souped up with Porsche running gear. He’s even had the opportunity to do a purist-approved restoration of the first Porsche racer that placed at Le Mans.

The shop turns out six or seven completed cars a year, most of which are the Emory Outlaw and the Emory Special. The Outlaw hews closely to Emory’s long-standing recipe of reworked mechanics: more powerful engines, improved brakes, and modernized suspension. These machines take a year to complete and cost about $250,000, plus the price of the donor car.

The Emory Special gets extreme body modifications, such as even better chassis hardware and a four-cylinder version of the Porsche 911’s six-cylinder engine. Specials take roughly a year and a half to complete, at a price of about $350,000 to $400,000 on top of the cost of the original.

Is a company that specializes in classics that ceased production in 1965 doomed to fade into history as its products age? Maybe not, thanks to a lifeline to the future from Porsche. The Stuttgart sports car maker’s latest models use thoroughly modern turbocharged, water-cooled engines in the brand’s traditional flat, horizontally oriented arrangement.

And critically for Emory, the cylinder count in these new engines is four rather than six, making them the correct size for use in a 356.

“It is my responsibility to continue to evolve that 356 design using all the parts Porsche has to offer,” Emory says, “to improve both styling and performance using the latest Porsche technology to accomplish that, be it water-cooled engines or hybrid-electric technology.”

Putting such technology into a classic 356 should keep the Outlaw label legit for the foreseeable future.