How the Czinger 21C Hypercar’s 3D-Printing Tech Will Transform The Automotive World

A mind-bogglingly high-tech manufacturing process unleashes a 1,350-horsepower, 250-mph rocket ship.

Photos by Robert Kerian

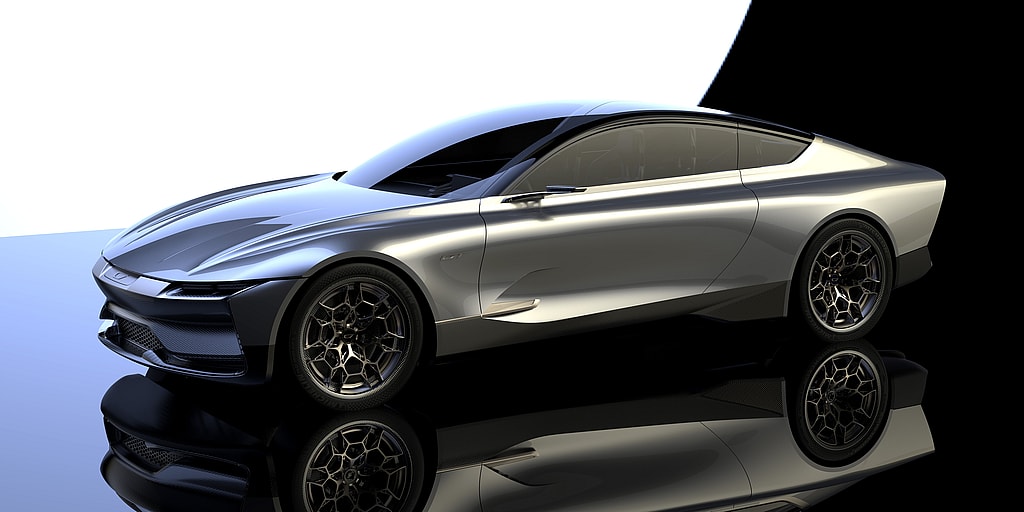

There are hypercars, and then there are hypercars. While most are designed from the white board to stir the imagination, not to mention the loins, witnessing the Czinger 21C roll towards us stimulates something completely different. Not two minutes from exiting the helicopter that flew us to the hot pavement of the Thermal Club, the 21C makes its eyebrow-raising debut: maybe it’s the way the silver skin gleams under the torrid Palm Springs sun—its voluptuous wheel arches, vast wing and aero bits catching the light and bending it to form.

Or perhaps more likely it’s the 21C’s unique seating layout: central, its greenhouse glass splitting the hypercar in half. Inside, twin seats bolt one behind the other, like a fighter jet. Suddenly you’re reminded of how this spaceship was built. Didn’t you hear it was 3D printed?!

When the huge scissor doors open up like a hangar, you’re beckoned to climb inside for hot laps. The heat is dizzying this spring afternoon on Thermal’s private racetrack. You’re unsure if it’s coming from the bulbous yellow sun hanging high in the sky, or if your body is radiating intensely from some reptile-brained alarm.

We pull on a helmet, climb in the backseat, strap on our seatbelt, and hear the driver’s voice crackle over our helmet intercom. “You ready?” he says from a meter ahead, under the same expansive glass canopy. “We’re gonna take one lap so you can get a lay of the land, then we’ll switch on Track mode and really turn on the jets.”

Since it’s a prototype we’re not allowed to actually drive the 21C this afternoon, but as soon as we pull out of the pit lane the visceral A-bomb immediately verifies many of Czinger’s seemingly absurd claims. First, its 0-60 mph clip of 1.9 seconds seems well within reach. A unique hybrid powertrain—mating an in-house developed twin-turbo 2.9-liter V8 with electric motors at each front wheel (powered by a 2.8 kWh battery pack)—generates a surfeit of boost: 1,350 hp and 1,061 lb-ft of torque. While we don’t even remotely approach the 253-mph top speed on the twisty corners of Thermal, those corners do prove the 21C’s most spectacular talent: balance.

“Czinger has a singular mission: to make the most technologically advanced cars in the world.”

With the high-pitched whine of the turbos complimenting the thrumming explosions of the V8, the Czinger launches down straights, scrubs speed with impact, and leaps into corners with alarming poise. G forces squeeze weird sounds out of my body, while takeoffs release reams of laughter. I’m living out all my Top Gun fantasies, except firmly planted to terra firma. The 21C’s lithe curb weight (2,900 lbs), torque and balance from the Formula One-like central seating orchestrate a truly singular driving experience. On the track there is nothing like it, and makes one totally reassesses traditional right- or left-hand driving configurations. This sensation of being equally distant from each wheel as you hit corners is paradoxically both reassuring and wildly novel.

You now remember the inspiration for the 21C: the SR-71 Blackbird. The legendary spy jet shattered the world record for both sustained altitude (85,069 feet) and absolute speed (2,193.2 mph, or Mach 3.3). It’s all starting to make sense. It also makes sense that the bleeding-edge Czinger 21C is quickly starting to gobble up its own record books. The hypercar has already captured Laguna Seca’s production-car lap record (previously held by the McLaren Senna) by more than two seconds, and then destroyed COTA’s production-car lap record (previously held by the McLaren P1) by more than six seconds.

The fact that a nascent startup is snatching records from Formula One-seasoned marques should send a hell of a warning shot to the most powerful brands on the planet. These track lap-records say more about actual holistic performance than any 0-60 time or top speed ever could.

And the strangest aspect of all? The car’s entire body and chassis—minus tires, wires and glass—are digitally 3D printed by Czinger’s parent company, Divergent. And while that may sound like a clickbait-y gimmick, it is far, far from it. Actually, that technology reveals the real purpose of the 21C: it is a proof-of-concept. A 250-plus mph Trojan Horse that draws us here to Thermal to witness, only to reveal that the story—the real story—rings much deeper, with much more profound possibilities.

“Don’t call it digital printing—this is a fully functioning, robust digital manufacturing system,” founder Kevin Czinger tells me a couple months later as we’re touring his company’s HQ in Los Angeles. Although it grabs all the headlines due to its innovation, 3D printing is only the second of three pillars that are the foundation for Divergent’s groundbreaking technology.

“We want to change the way structures are produced, and we want to do it because we think there’s a new technology that’s going to be more efficient and sustainable,” Lukas Czinger, Kevin’s 28-year old son and partner, tells me. After revolutionizing the automotive industry, Divergent aims to take these practices beyond—to aeronautic, marine, defense, etc. The process they’re proposing, and proving the efficacy of with the 21C, has the potential to disrupt manufacturing as we know it.

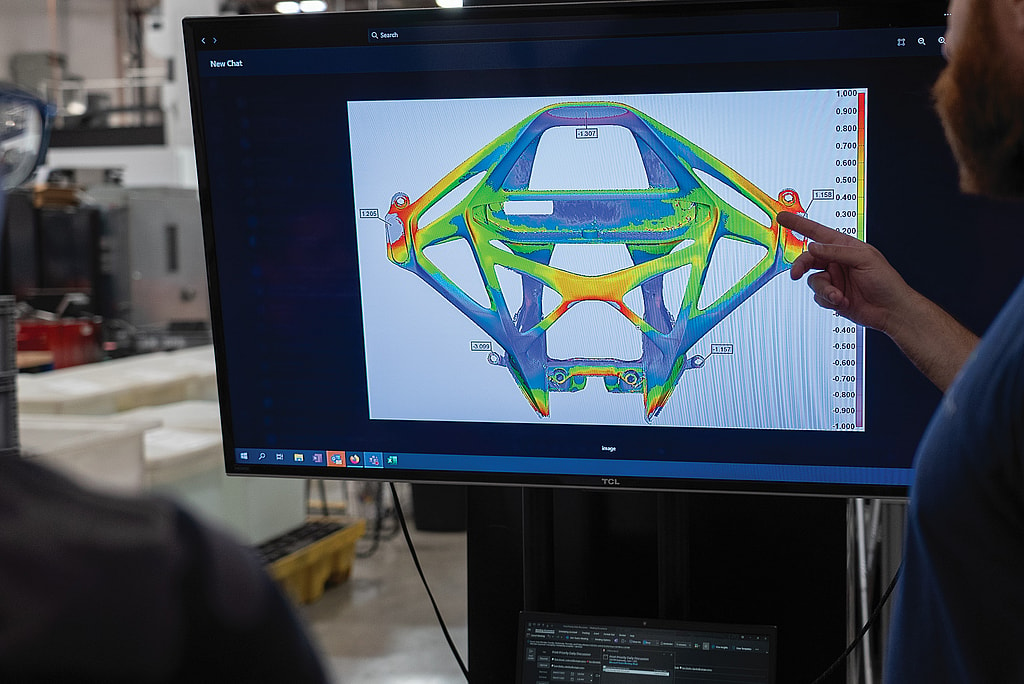

First the object—be it door, sub-frame, brake caliper—must be designed, for which Divergent employs advanced artificial intelligence to imagine infinite options which are theoretically tested and corrected at supercomputer speeds. When it’s finished that object is the optimum solution for its given parameters. “Boom, you have the perfect structure,” Kevin states. “When you see that rear frame, from an optimization standpoint that’s actually a perfect structure. For the first time in human engineering history.”

These parts often look unlike any automotive part you’ve ever seen, almost biological in nature, a phenomenon Czinger is accustomed to. “What the AI does is unleashes human creativity,” Kevin says. “What I was focused on was the intersection of human creativity and the AI simulation that you could do for design.”

Why now, you may ask? While concepts like neural networks and the Von Neumann universal constructor began in the 1940s, they remained strictly theoretical. Technology lacked the processing power to make it happen, but in the last decade with big data and high-performance computing all that has changed. “Instead of being trapped in Leonardo’s notebook these things can come alive,” Kevin says excitedly, “because you’ve got the tools.”

Second comes the digital printing of the parts from a proprietary aluminum alloy Divergent has patented (they currently have secured over 500 patents). Because no 3D printer existed fast and accurate enough for Divergent’s needs, Kevin helped design one with German tech firm SLM Solutions. Each machine can print about a kilo of aluminum per hour, making the process scalable: the quicker you want to manufacture, the more printers you buy.

“The 21C explodes down straights, scrubs speed with impact and leaps into corners with alarming poise.”

Then lastly comes the fixture-less assembly system—a complex orchestration of a dozen robotic arms that seamlessly fuse the pieces together. taking any number of 3D printed parts and bonding them together into their final structure without changing any hardware. Rear frame, front frame, full chassis, doors, all of it.

The end result is Divergent/Czinger can re-engineer a part in hours, not months. Neither the printer nor assembly cell requires any hardware modifications nor changes to assemble a new design. As a Tier One supplier for a major auto manufacturer they were recently tasked to move a rear frame by a centimeter. Traditionally that could take months to build a new part, as it has to be redesigned and engineered, casting machinery has to be modified, etc.

“We’ve been able to iterate at a fraction of the time as an OEM,” Lukas explains, noting they delivered the new part in three days. “We’re the only ones on the planet using this design software, this manufacturing method, these materials.”

Walking through the inner bowels of the Divergent factory you see lasers dancing through glass, 3D printing parts with heretofore-unavailable precision. You walk past the robot arms that bond the parts together. Just a stone’s throw from Tesla and SpaceX headquarters, Divergent’s location doesn’t feel like a coincidence; more like a silent threat to one of the most powerful tech companies on Earth.

We walk to the back of the factory floor to the design center, where we see for the first time something no-one outside of their 200 employees knows about: a digital sketch of the four-door ‘Hyper GT’ that Czinger will unveil in a couple months at The Quail Motorsports Gathering during Monterey Car Week. Kevin has a big grin on his face as he shows it to me, swearing me to silence. I oblige.

“If you want to create super-cool things in the 21st century, you have to create these tools first,” argues Kevin, listing off-the-record what other goodies Czinger has on its horizon. “And then you can create these cool things, which is the fun part. The thing that human beings take ultimate pride in is the product.”

Czinger promises the Hyper GT will be the highest performing four-seat GT vehicle in the market, offering real-world packaging (i.e. comfortable seating for four adults plus luggage space) with the top-level performance and revolutionary production methods of the 21C. Capped in production, 21C owners will get first dibs on the Hyper GT, which they vow will be “segment defining.” For now, that’s all he’s revealing.

(Czinger)

Lukas then adds a simple statement that for some would ring as corporate hyperbole, but given what they’ve already accomplished demands attention. “Czinger has a singular mission,” he tells me point-blank. “To make the most technologically advanced cars in the world.”