Behind The Wheel At 24 Hours of Le Mans, The World’s Wildest Endurance Race

We put the pedal to the metal at the greatest motorsport event on the planet.

I have driven faster. But so has my copilot. So much faster that most of you would be blubbing like small children poked in the eye with a stick. Pleading to slow down to the point where the world made sense again.

It’s Le Mans 2019. Famed racing driver Derek Bell and I are belting down the Mulsanne Straight flat out in an original Bentley from 1930. At a tear-inducing 79 miles per hour.

A far cry from Bell’s days pushing the outside of the envelope going faster than almost anyone has since. Epic. Magnificent. Emotional.

The “24 Heures du Mans” Automobile Club De l’Ouest’s endurance race was first held in 1923 in and around the small town of Le Mans in northwestern France. Each team of drivers shares a car, and the challenge of achieving as many laps as possible, without breaking down, in 24 hours.

One of the first entrants was a Bentley driven by John Duff and Frank Clement in 1923. They didn’t win the first time around. But their cohort of gentlemen racers, the mythical, “Bentley Boys” went on to win five times in the next seven years.

And this year, for Bentley’s 100th anniversary, one of the streets of Le Mans that Bell and I whipped ‘round was renamed “Rue des Bentley Boys” in their honor.

As I sat in Derek’s passenger seat parading around this legendary track, I had a lot to ponder. Derek won Le Mans overall five times.

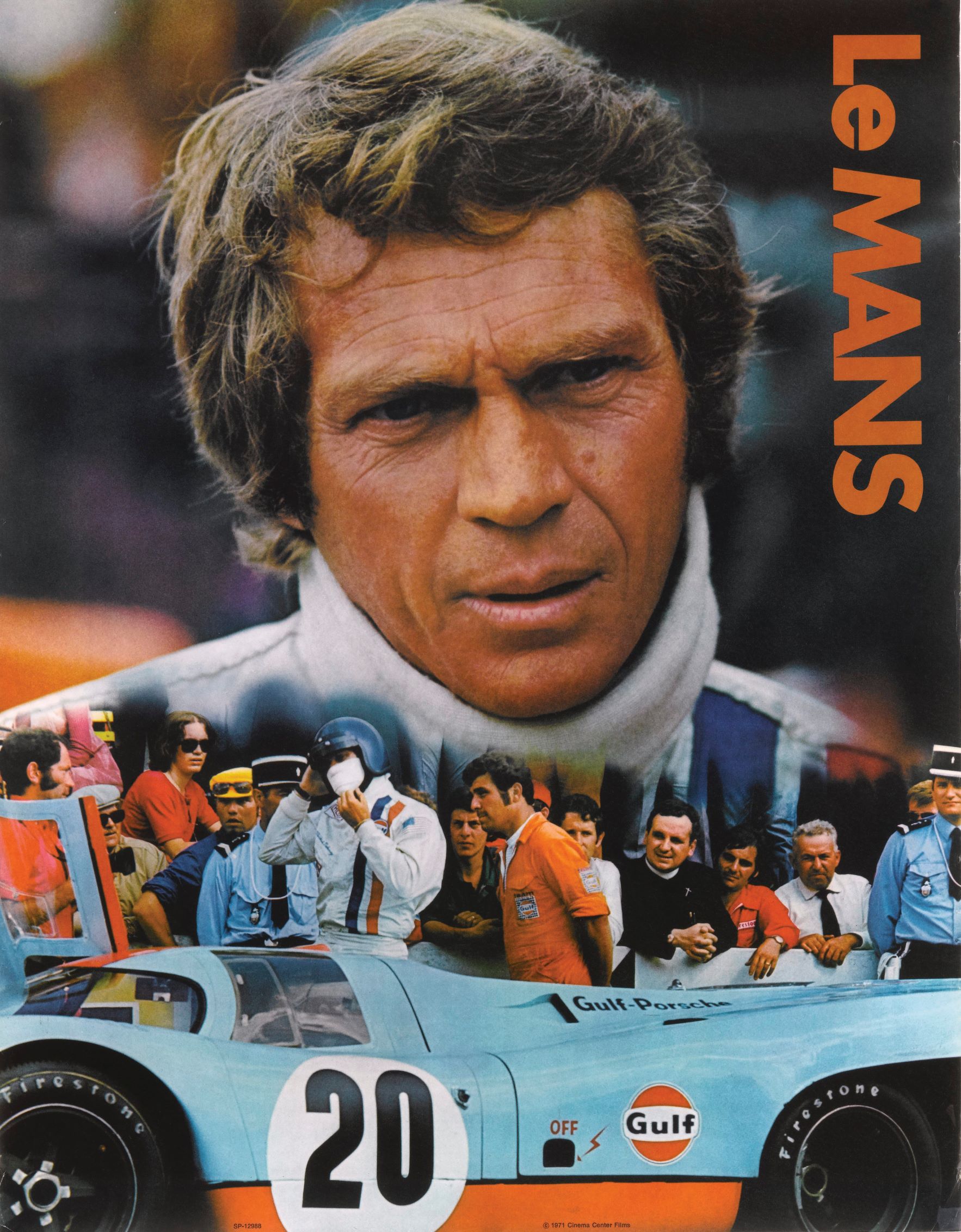

Visions of Steve McQueen and his 1971 film Le Mans, Porsche 917s, Enzo Ferrari, Ford GT40s, and all the ghosts of legends past and present flickered through my mind.

He was showing me his form at the wheel bedecked in leather driving gloves and a smile, regaling me with tales of catapulting down the same straight at 246 mph in 1971.

Strapped into a voluptuous, wide-hipped, glorious, thundering, blue and orange Gulf Racing Porsche 917. A rumbling, slippery, missile that rolled and flexed and gave you a nod and a wink before everything let go. Before you smacked into the Armco barrier; or worse, the trees, engulfed in pyrrhic flames.

The chicanes that were later added to the famed Mulsanne Straight did not exist at the time. And neither did safety. Or Brembo brakes. Or computers. But glory and glamour did, with plenty to spare.

The aesthetics established back then continuing to inspire every brand with macho pretensions today. Just cast your eye over a photo of McQueen during filming on Le Mans, sporting a racing suit and his now iconic Heuer Monaco watch, surrounded by cars in bright popping colors and bold racing stripes.

Then close your eyes and reopen them in 2019, and see. And dream of owning Count Rossi’s early 1970’s street legal Martini Racing Porsche 917. Derek Bell was there in 1970. Flying down the track through the Maison Blanche corner with McQueen tailing him just as fast.

The living, breathing, flesh incarnate of a line from the movie, “Racing is life. Anything that happens before or after… is just waiting.” McQueen had convinced the 1970 Le Mans race drivers to join his crew for the movie. Who better to lap the track than the guys who actually did it for death or glory, after all?

And, of course, Derek confirmed what we already knew. Steve was the real deal and could drive with the best of them. McQueen came second in the 12 hours of Sebring in 1970 with Peter Revson in a Porsche 908 and had wanted to enter Le Mans himself that year.

Rumor has it the company insuring the movie wouldn’t underwrite it if he did. So he chose to film, not race. One day on set, after a day of lifting off to 70% on each take, Derek was bored.

He decided full race speed was in order for the final take. Flying through the corner at Maison Blanche in his Ferrari 512 without lifting, he saw McQueen in his shadow all the way.

Then as he slowed to a halt and hopped out of his car McQueen came running over, shouting, “This bloody lunatic just tried to kill me.” “You didn’t have to follow me,” Derek replied.

McQueen told Derek he would get him back. And he did. Egging him on in a motorcycle challenge around the track while they were still filming the movie. Derek ended up in the garbage dump covered in rubbish. Steve ended up with a laugh, and chalked the score to 1-1.

At this year’s race I was camped out in an RV by the permanent Bugatti Circuit part of the track since Thursday as it’s the only way to truly immerse yourself in something like this.

It’s now 12 am on Sunday, and the cars have been racing since 3 pm on Saturday. I have an eight million calorie jamón ibérico sandwich in my hand. Procured against a backdrop of floodlights and fairground rides from a food stall of gnarly Iberians with grizzly, muscular, forearms; and a passion for black, acorn-gorged pigs.

Fat, salt, sugar and protein are hitting my system and temporarily kidnapping the pleasure centers of my brain. Caffeine is sloshing around at levels high enough to erase all thought of sleep. And there is a good chance I would fail a breathalyzer test.

But I am here to soak up the atmosphere. Not to attack each corner at breakneck speed with metronomic precision as the drivers are doing.

In the background you hear what sounds like a swarm of steampunk flying insects. Playing a riff on Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.” With the deep thumping bass of the Corvettes, the popping tenor of the LMP cars, and the high pitched buzzing of Porsche 911s.

The Brembo Racing crew and I are about to attempt to bypass security and watch the action from a corner of the track in the small village of Mulsanne. The Mulsanne. By climbing onto workmen’s cabins at the corner at the end of the infamous straight.

I had been told that this was one of the best places to watch as the cars come flying out of the darkness at over 200 mph, before decelerating to a fraction of that in a few hundred feet, thanks to carbon Brembo brakes lit up like fireflies in the dark.

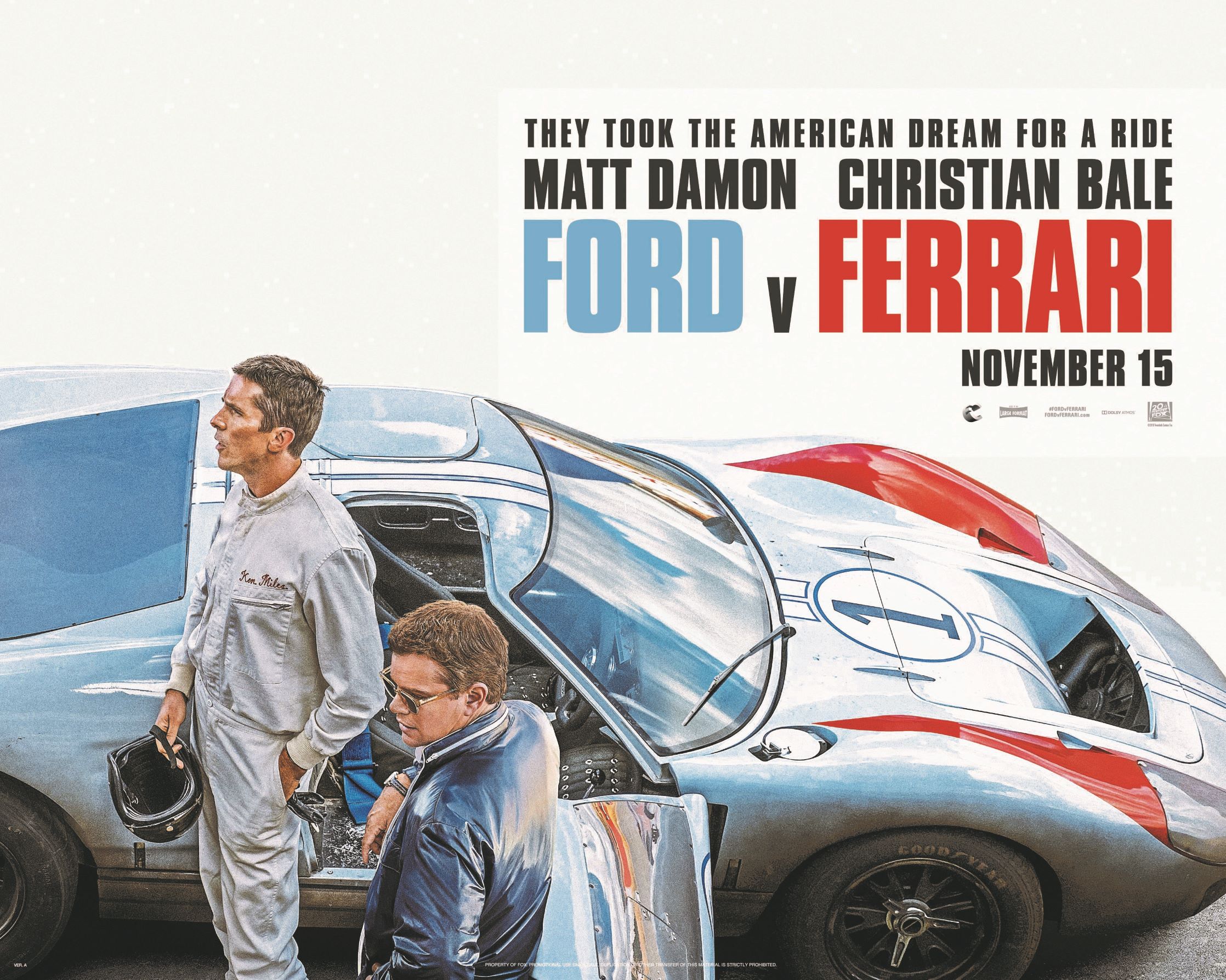

Ferrari and Ford are again locked in their 50-year-old battle, soon to be immortalized in the new movie, Ford v Ferrari starring Christian Bale (see sidebar below).

Another actor, Patrick Dempsey, is leading his own Porsche team here at Le Mans hoping for a repeat victory in their class, while at the top of the technological totem pole Toyota is racing its LMP1 Hybrids against itself.

Le Mans is a place of mists and magic and pilgrimage. Glory, glamour and legend hang in every breath in the air. Mingling with the smell of beer, sweat, grease, and high octane racing fuel. And death, and glory. This is holy ground for motor racing fans.

As Harry Tincknell, driving for Ford Chip Ganassi Racing this year in their failed bid to recapture Ford’s 1960s GT glory days told me, “drivers want to win Le Mans more than at any other race.”

One look at former Formula One Champion—and now two-time Le Mans winner—Fernando Alonso shoehorning himself into the Toyota Gazoo Racing LMP1 car and you immediately understand this.

This race has always drawn drivers to its sadomasochistic siren call. Across disciplines, continents, and oceans. For this is the magical charm of Le Mans.

A place where as another alumnus, Mario Andretti, who drove the original Ford GT40s, once put it, “If everything seems under control, you’re just not going fast enough.”

Le Mans on Film

Steve McQueen’s 1971 film Le Mans remains the definitive movie about the iconic endurance race. But that may change in November when Ford v Ferrari from James Mangold, director of Marvel’s The Wolverine and Logan, gets released.

The autobiographical action flick stars Matt Damon and Christian Bale in the tale of Ford’s epic triumph over longstanding Le Mans champs Ferrari with the incomparable Ford GT40 in 1966. The GT40, designed by Carroll Shelby (played by Damon in the film) went on to win Le Mans three more times in 1967, 1968 and 1969.

It all started because of a feud; in 1963 Henry Ford II had a deal in place to buy Ferrari. But when Enzo Ferrari backed out at the last minute, an enraged Ford told his lead negotiator to “go to Le Mans, and beat his ass,” whatever the cost.