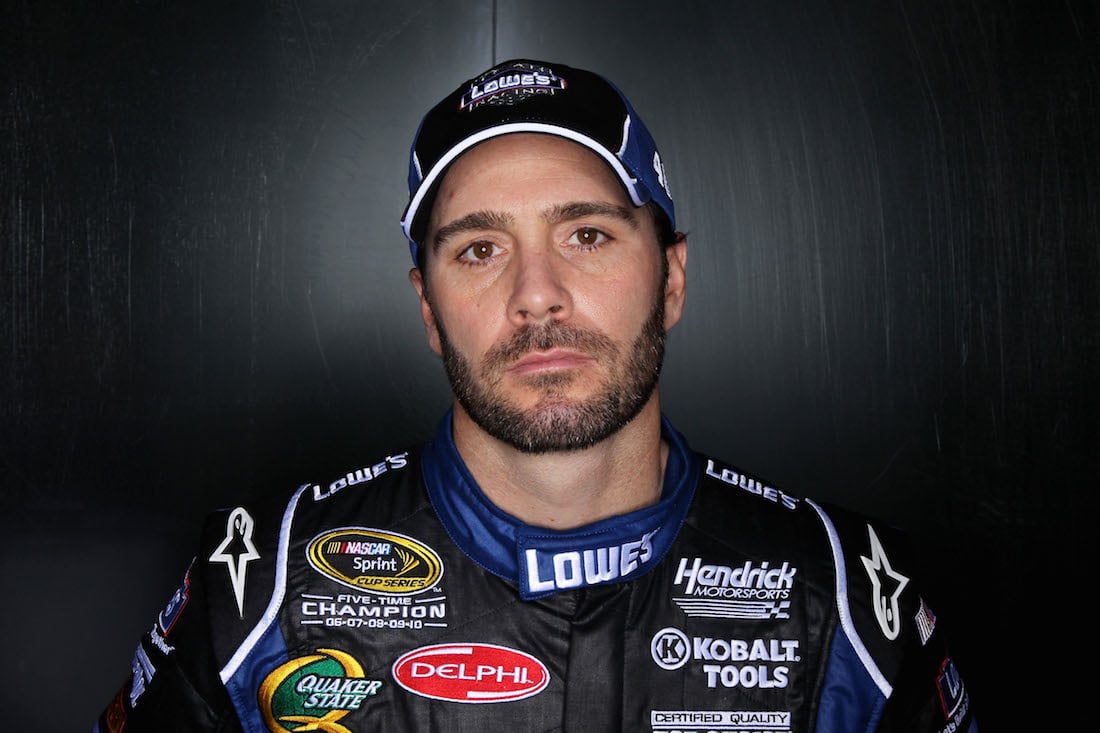

How Jimmie Johnson Drove Himself To Become NASCAR’s Biggest Superstar

Can the seven-time champion lead the sport into the future?

It was down to two. The Monster Mile, a concrete racing oval at Dover International Speedway in Delaware with a reputation for grinding expensive stock cars into junk, had done its work.

Only the number 48 of Jimmie Johnson and the number 42 of Kyle Larson were in position to take the checkered flag. Larson had the faster car by far and had dominated the race, leading for 241 laps. Meanwhile, Johnson had negotiated the Monster like a truant pleading for leniency. He was running on worn tires; he’d been in the lead for a grand total of four laps.

Yet now, a late yellow caution flag, which requires a driver to slow down because of a hazard on the track, meant the outcome rested on a final restart. When the green flag waved, Johnson feathered his Chevy SS past Larson’s Ford to beat him

into turn one, and held

the lead throughout turn

two when a last-lap wreck

behind both of them ended

the race in number 48’s

favor.

“You put that rabbit out in front of me and

I’ll chase it down. It’s just

the way I’ve always been,” Johnson said afterward.

Larson, a rising star and

just 24 at the time, was left

to rue the craft and craftiness of the 41-year-old veteran driving the second-

best car, who had just left

him in the rearview. “I

got to get better at that,”

Larson said.

Don’t sweat it, Kyle.

You’re not the first rabbit

Johnson has run down. In a prior win at Bristol Motor Speedway earlier in the season, he had bested Clint Bowyer, taking the lead on lap 480 of 500, leaving an outstanding racecar driver sputtering like a misfiring engine.

“It’s Jimmie Johnson,” Bowyer said afterward. “You try everything you possibly can, and I was starting to do some pretty desperate things…and then you just realize.”

The win at Dover was Johnson’s 83rd career NASCAR victory, a mark that tied him with Cale Yarborough for sixth of all time, one behind Bobby Allison and Darrell Waltrip. It was his third victory of the season, not that it mattered much: He had already qualified for NASCAR’s year-end playoff series way back in April.

For the rest of the regular season, Jimmie Johnson plays with house money. “He may be the best driver our sport’s ever

seen, and we’re watching it,” says former NASCAR champion and current NBC analyst Jeff Burton. “And I don’t take that lightly. I raced against Dale Earnhardt.”

Johnson has won often and won everywhere—in the restrictor-plate pack racing of super speedways like Daytona, in frantic half-mile circuits like Bristol, or in places like Sonoma. Last year, he won his seventh NASCAR championship, duking it out with 15 other drivers in an NCAA bracket–style elimination series over the final 10 races, with the four finalists facing off at the Homestead-Miami Speedway. Figure on him to be there again this year.

NASCAR needs superstars such as Johnson more than ever in its effort to rev fan interest and reverse a decade-long slide in attendance and TV viewership. NASCAR’s base—white, male, and old—remains strong, but it’s dwindling and clearly not coveted by advertisers.

Holding on to sponsors has been an issue. While new faces such as Chase Elliott, Daniel Suarez, and Ryan Blaney are emerging talents, Dale Earnhardt Jr. is in his final year, and stars such as Carl Edwards, Tony Stewart, and Jeff Gordon retired recently.

Johnson was once criticized for being boring because he won too much. Sort of in the way Roger Federer at his peak was “boring” for beating everyone. Now he has become the sport’s bridge between the glory days and the need to grab a new generation of fans. “It’s really about finding teenagers that are developing that fandom for a particular sport and capturing them,” he says. “The competition side of our

sport has never been stronger.”

To play to an increasingly short-attention-span audience and beef up the competition, NASCAR has introduced stage racing. Under this format, there are races within the race. Drivers can earn playoff points for winning stages that typically end at the quarter and halfway marks, plus the big payoff for winning the whole shebang.

That’s changed the level of aggression, along with the strategies. “Track position is so vital: the fact that you know that a caution is coming. It takes a lot of strategy out of the pit calls. It’s changing the game, requiring the teams to be faster and bring a faster racecar, and for the drifters to drive harder. It’s demanding performance out of us,” Johnson says.

Johnson is not the stereotypical NASCAR driver—not that there is one anymore. He’s one of the fittest drivers on the circuit. A water polo player in high school, he has completed a number of triathlons, with the goal of eventually completing a full 140.6-mile Ironman triathlon.

In the off-season, you’re more apt to find him, his wife, and two kids in the West Village in New York City, where he owns a condo—although he and the family spent last winter hanging out in Aspen, where he also owns a home. His third is in Charlotte, North Carolina.

He grew up blue collar in California, the son

of a heavy machinery operator and his school-bus-

driving wife. Johnson began racing peewee motorcycles at age five and soon became a kid phenom.

After tagging along with his father to local off-

road races, he eventually found a ride and would

win six off-road racing titles, including the 1995

SCORE Class 8 World Desert Championship.

He was SCORE’s Rookie of the Year that year as well. Signed by Hendrick Motorsports in 2000 and mentored by another Californian, Jeff Gordon, he quickly began winning races on paved surfaces.

There are two ways to win a NASCAR race, according to Burton. You can either race the track or you can race the other guys. “Jimmie’s success isn’t in his aggression and how he races other people,” Burton explains. “It’s the speed he is able to generate by aggressively attacking the racetrack. They look like the same thing from the outside, but they are not.”

Nobody is better at negotiating a way through a pack of angry 3,300-pound racecars and finding the optimal position on the track than Johnson. “What I’m known for is, the longer the race, the better I do,” he told me.

That means preserving the car, saving the tires until the car has what Johnson calls that “soft, Cadillac feel.” Some of his preservation skills stem from those motocross and off-road endurance races. “In a dirt environment, you had to think a lot about risks versus rewards,” he says.

Whether your strategy is to trade paint or lay back, you still have to get over the finish line first, and Johnson’s passing skill is his kill shot. Last year he led NASCAR in a stat known as “quality passes”—blowing by the top 15—with 2,267 see-ya-laters. “In racing, there’s always a physical and emotional ratio,” Burton says. “He physically has the ability to feel the race- car, to know what he’s looking for; he has those things physically. Emotionally he has the drive, the willingness to push himself, to never settle.”

Nor does it look like Johnson is running out of relentlessness anytime soon. He recently signed a three-year contract extension with HMS. “The willingness to compete is still there,” he says. “I

worked so hard to get to this point in my career, and I’m also fortunate to be in a sport where experience still makes a difference over a young body. I love what I do. I’m not ready to stop.”

That is great news for NASCAR. “He is a fantastic representative for us both on and off the track,” says NASCAR chief marketing officer Jill Gregory. “The amount of respect he gets is gratifying to see. It’s a huge accomplishment for us as a sport.”

Johnson’s competitors are grateful to have him too. They will tell you as much. But they also know that in Jimmie Johnson’s eyes, they are all still rabbits and he is the hunter.

Check out Maxim’s September issue, on sale August 22, and subscribe here.