‘Drive Time’ Taps Best Luxury Watches For Driving, Racing & Motorcycling

Fast times.

(Courtesy Rizzoli)

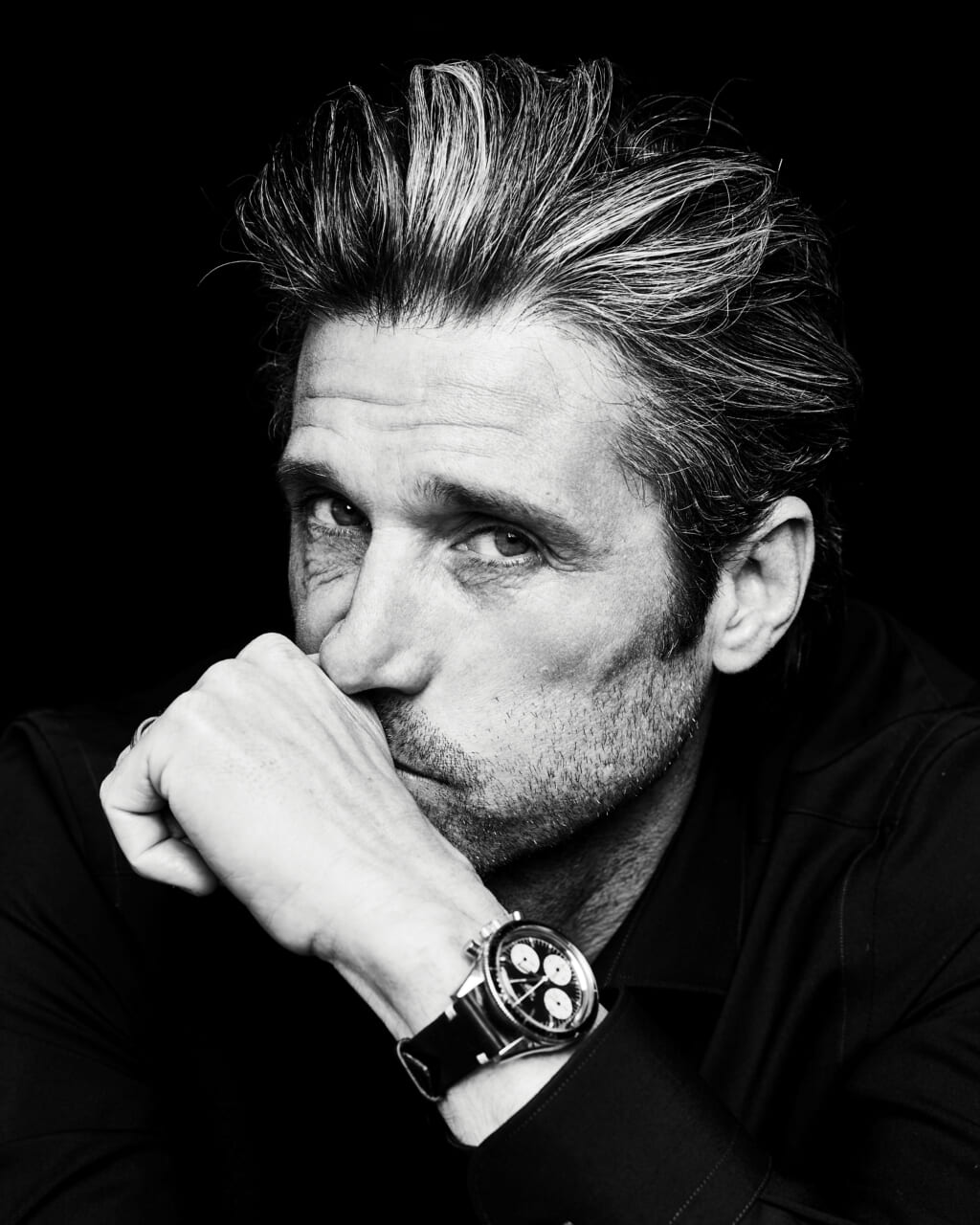

“What’s so alluring about cars and watches is the level of meticulous design, engineering and savoir faire behind the manufacture of each.” As both a car and watch collector, not to mention a racing driver and TAG Heuer brand ambassador, actor Patrick Dempsey knows whereof he speaks.

(Courtesy Rizzoli)

“They’re both investments spurred by passion and emotion, heritage and futurism—vintage models are sought after like cult totems, while modern innovation ensures a steady evolution into the present and beyond. There’s no limit to the connoisseurship inherent to each.”

(Aston Martin)

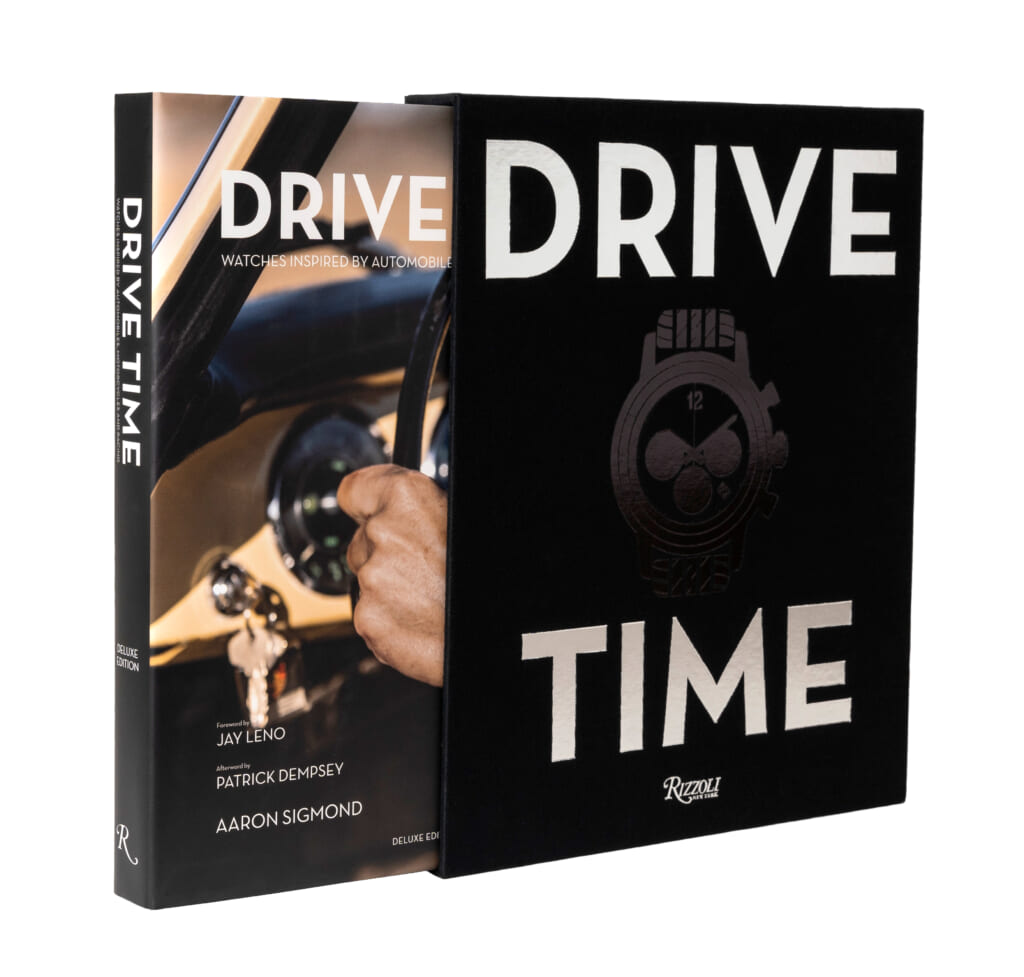

His remarks appear in the afterword to a cool new deluxe edition of the most comprehensive and beautifully-designed book ever created celebrating the connection between cars and watches: Drive Time, by Aaron Sigmond, author of numerous top-shelf luxury lifestyle books, just published by Rizzoli.

(Courtesy Rizzoli)

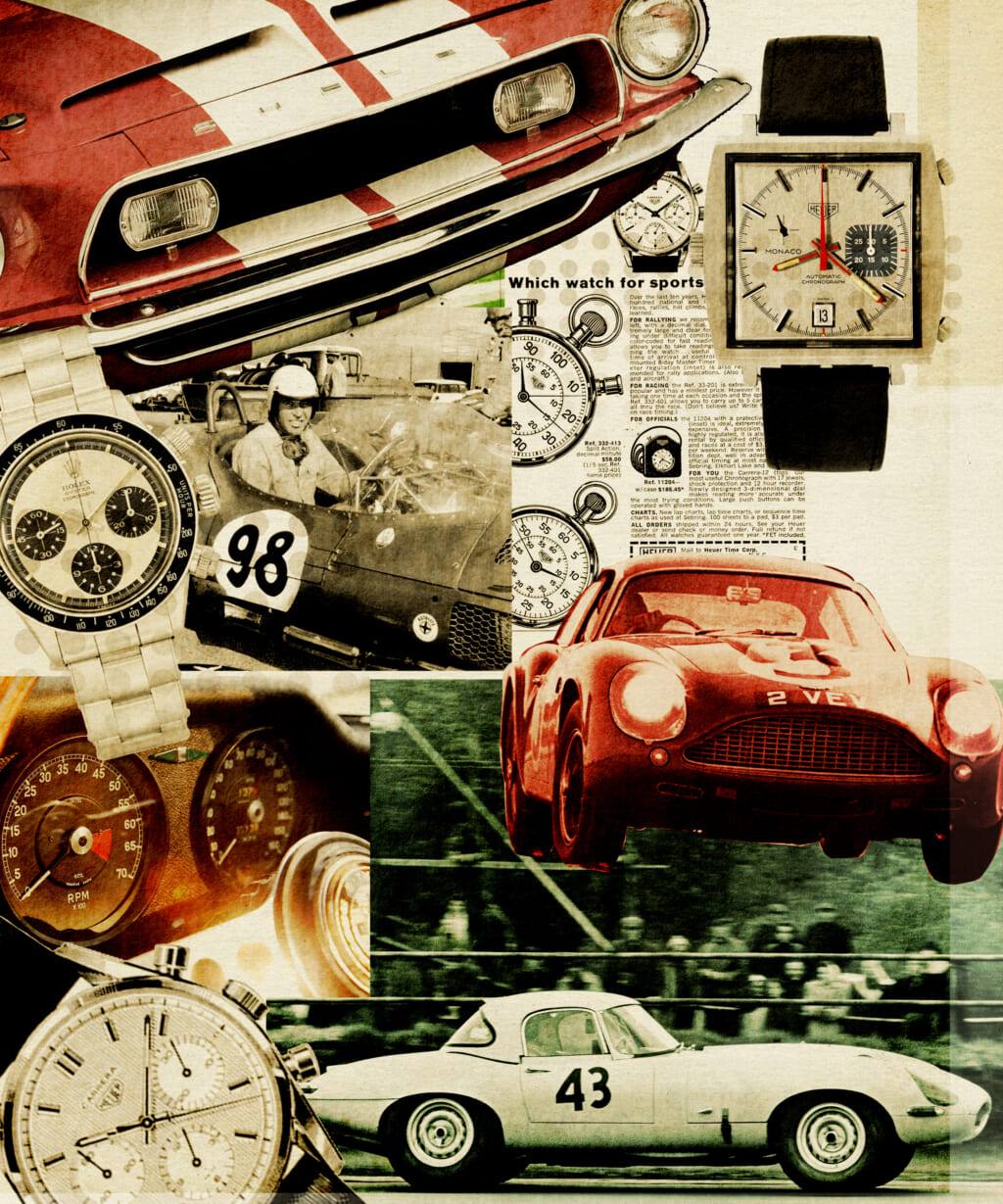

In addition to detailed chapters on the history of the car-watch connection is a deep dive on more than 100 auto-inspired watches from the mid-20th century, from the Rolex Daytona and the Heuer Autavia, Carrera, and Monaco, through more contemporary collections including the Chopard Mille Miglia, Breitling by Bentley, Porsche Design, Hublot Ferrari, IWC Mercedes-Benz AMG, and Girard-Perregaux x Aston Martin collections–all of them mechanical marvels.

(Aston Martin)

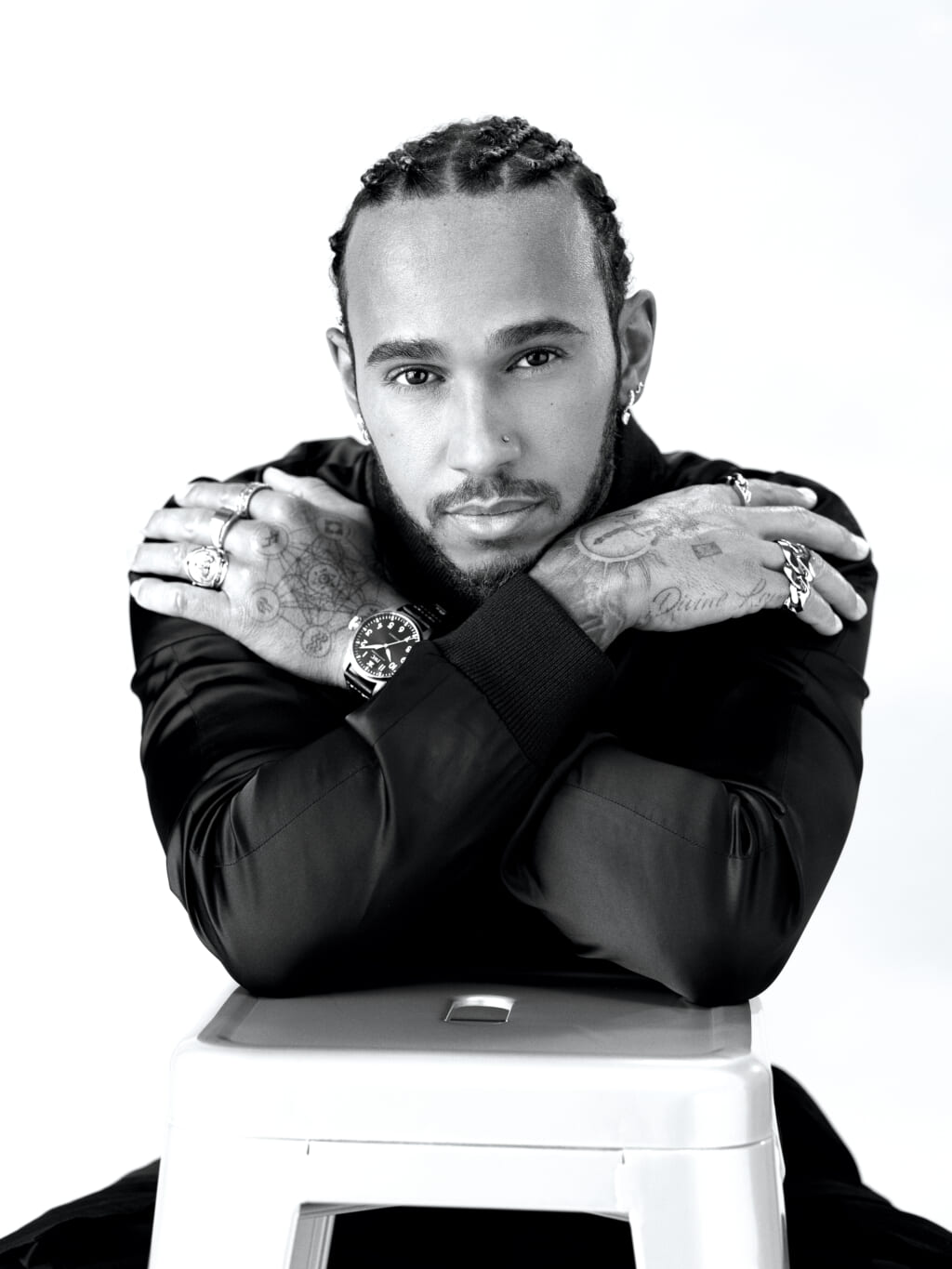

“Mechanical watches and automobiles have a lot in common,” as another notable car and watch collector, Jay Leno, points out in the book’s foreword.

“For example, a contemporary twin-clutch paddle-shift transmission might be faster than a conventional manual gearbox, but I don’t think it’s more satisfying to drive. Then consider this: An electronic watch might keep time to the hundredth of a second, but that’s nowhere near as rewarding as that quiet moment when you wind the crown on a mechanical watch each evening before you go to bed.”

(TAG Heuer)

Leno reveals that his watch collection now numbers about 100 pieces. “Like automobiles, paintings, even buildings, the first thing you notice with a watch is how it looks,” he muses. “Are the numbers cool? Is the typeface interesting? Another good sign is a second hand that moves chronometrically—click, click, click—like the five-inch Smith’s speedometer on a Vincent Black Shadow. That says quality, and it’s why so many watches now copy the dashboards of famous automobiles.”

(Courtesy Rizzoli)

The great watch designers, Leno declares, “are like great automotive engineers: the Duesenberg brothers, W.O. Bentley, Harry Miller, Leo Goosen, Vittorio Jano. They’re the same kind of guy: inventive, meticulous, very clever.”

(Rizzoli)

In the first chapter of the book, Sigmond calls automobiles and mechanical watches “two of the greatest mechanically power-driven inventions of the 20th century.” And while he notes that “the mass-produced automobile and the wristwatch grew up side by side, forging peerless style, design, and shared mechanical engineering along the way,” the relationship between the two began much earlier.

(Rizzoli)

“From the time automobiles first roamed the earth, there have been watches…. created specifically for cars and drivers.” And the company that started it all was Alfred Dunhill Ltd., or, as it was called when founded in 1893, Alfred Dunhill Motorities.

(Aston Martin)

“In 1911, a year after Dunhill introduced its right-side-up car watch, Heuer, the precursor to the company and brand now known as TAG Heuer, debuted ‘Time of Trip,’ the first dashboard-specific chronograph,” Sigmond tells us. “By midcentury it would create and launch the split-second Sebring stopwatch for race timekeeping, as well as the Carrera and Monaco Chronograph wristwatches.”

On and on the timekeeping innovations went, and by 1915, “another of today’s familiar fine-watchmaking names, Jaeger-LeCoultre (at the time called LeCoultre & Cie), had begun manufacturing dashboard instruments for the prestigious automobiles of the day.”

By the early 1940s, “the wrists of more discerning—not to say wealthier—motorists glimmered” with drivers’ watches produced by the likes of Cartier, Universal Genève, Vacheron Constantin, and LeCoultre.

And as racing gained popularity, so did the new racing chronographs that “bore brands and model names quite familiar to modern eyes: Breitling Navitimer, Omega Speedmaster, Rolex Daytona, and a bounty of Heuer chronos such as the Autavia, Carrera, Monaco… As Henry Ford famously observed, ‘Auto racing began five minutes after the second car was built.’ Drivers had to time it all somehow.” The rest, as they say, was history—though hardly lost time.

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2022 issue of Maxim magazine.