Photography Legend Slim Aarons’ Sexiest And Most Stylish Snaps

The late, great photographer described the aesthetic from his most prolific period as “attractive people doing attractive things.”

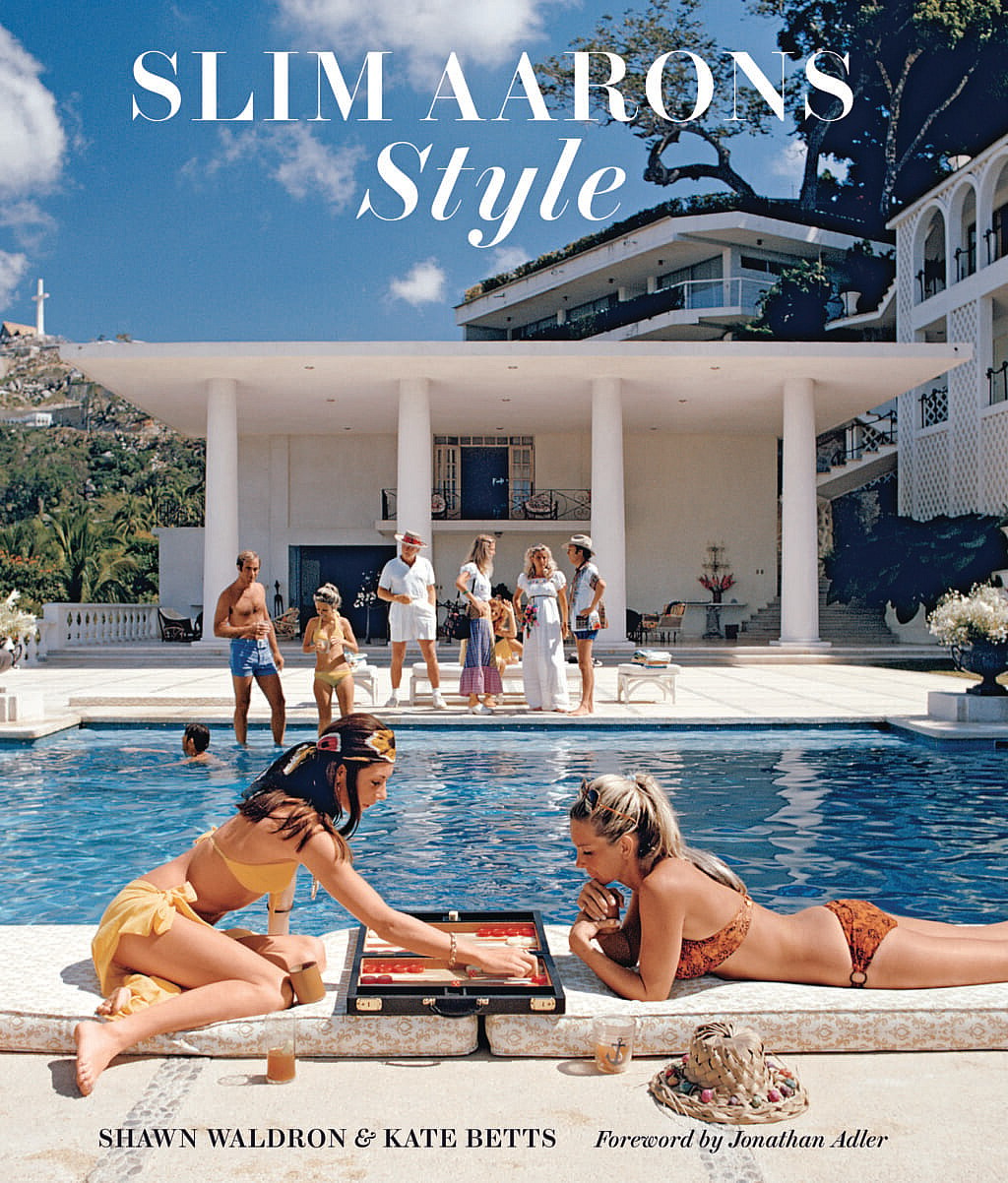

Acapulco, 1972 © Slim Aarons/Getty Images Courtesy of Abrams

Asked to define his work during his most prolific period, the late, great Slim Aarons (1916–2006) unhesitatingly declared: “Attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places.” So well and so distinctively did he document them, the sheer ripple effect of his influence is hard to calculate, even 15 years after his death.

Aarons, who was born in the Hudson River Valley and got his start as a war photographer before finding his true milieu in Hollywood in the 1950s, was unrivaled in focusing solely on his idealized subject matter, to the exclusion of all else.

A pre-race sports car lineup during Bahamas Speed Week, Nassau, 1963. The race was discontinued in 1966 and then revived in 2011 © Slim Aarons/Getty Images Courtesy of Abrams

As interior design guru Jonathan Adler notes in his foreword to Slim Aarons: Style, recently published by Abrams and one of the most striking anthologies of Aarons’ work to date, “In Slim’s world, the dramatis personae are never to be found staring at the horizon with existential terror. They are, in sharp contrast, frozen during moments of heavenly becaftaned, unapologetic self-indulgence.”

As for his influence, Adler declares, Aaron’s impossibly beautiful photographs were nothing less than “the big bang of FOMO that made Instagram possible.”

In his introduction Shawn Waldron, the beautiful book’s co-author and curator of the Getty Images and Slim Aarons archives, elaborates that, “Slim’s photographs are portals to another place where the sun is shining, the grass resplendent, the pool temperate, and money, well, we don’t talk about that.”

Holiday makers at Canzone del Mare at the Marina Piccola, Capri, 1954 © Slim Aarons/Getty Images Courtesy of Abrams

Slim’s greatest skill, Waldron writes, “and the reason his photography remains so enchanting, was his ability to capture the privileged in unguarded moments without judgment or prejudice. He was neither sycophant nor critic. Designers, stylists, and the fashion world at large have embraced his photography for more than three decades because the people and places in Slim’s pictures appear, in the immortal words of Diana Vreeland, ‘simply divine.’”

Waldron cites the likes of Ralph Lauren, Tory Burch, Sid Mashburn, Tom Ford, Diane von Furstenberg, Michael Kors, Paul Smith, Anna Sui, Jonathan Adler and Jack Carlson of Rowing Blazers among those who have paid homage to Aarons in their work.

Having examined the source material, Waldron explains that the most stylish magazines of the day— Holiday, Harper’s Bazaar, and Town & Country— “originally published Slim’s pictures as reportage and surrounded them with serious articles about upper-class life and rituals. The images were given a second life as designers, photographers, and creatives turned to Slim’s collective output as a form of visual inspiration in the 1990s and 2000s.

Today, his work has found a new audience among the Instagram generation; his color work in particular aligns with their obsession over surface, saturated color, and exotic locales. This new gaggle of devotees is not as overtly concerned with the who, when, and where of the photographs as they are with the broader lifestyle. No one has shown us the conceptual Good Life from the inside out better, and for longer, than Slim.”

His work for Holiday in particular was “critical in Slim’s evolution as a photographer and the development of his artistic voice and vision,” Waldron states. The thousands of photographs Slim shot in the second half of the 1950s provided the framework for what became his trademark: charity galas and debutante balls, assemblies and civic councils, royals, women shopping or wearing couture gowns posed in stately homes, outdoor sport and hunting, private homes, clubs and resorts, and a stream of patroon and old-world families, businessmen, artists, writers, and intellectuals.”

His co-author Kate Betts, former editor of Harper’s Bazaar, notes in her own essay for the Abrams book, that Aarons used his charm and journalistic training to “gain access to the private domains of the wealthy and socially well-connected, slipping into country clubs, onto yachts, and behind the gates of vast villas…. Porcelain, pools, horses, polo mallets, Porsches, Greek ruins, tufted velvet sofas, and the polished teak of Riva powerboats were among the many accessories appearing in Aarons’s photographs, purposefully staged to convey the essence of a subject’s style as carefully as a fashion stylist accessorizes a model with a Gucci handbag or an Hermès scarf.”

Colorful holidaymakers aboard a yacht in Bermuda, 1970 © Slim Aarons/Getty Images Courtesy of Abrams

Betts reveals that Aarons always traveled light, “carrying little more than a Leica and a tripod, and in a way he anticipated the spontaneous—not to say compulsive—picture-taking of the iPhone-toting Instagram generation that defines so much of contemporary style. Taking hundreds of thousands of images over the course of his career, he found his signature in the environmental shot, pulling back the lens and framing subjects in their settings.”

She adds that, “The collection of images Aarons produced as he moved through the social circles of Palm Beach and New York… were as noteworthy as his impact on the world of style was indelible. Through Aarons’s work you can read the evolution of style across four decades, a statement about how to live, not just what to wear.”

Thus, she sums up, “Slim Aarons was a man of his time, a shaper of what he observed and observer of what he shaped. In every photograph he took, Aarons arranged the view—his view—with careful consideration, instructing a subject to change his jacket, or hold a drink, pulling back the camera so an entire mid-century house and Palm Desert landscape would come into view behind a pool where two women gossiped; or simply framing a Newport tennis match in a round trellis window…. It is hard to imagine anyone today having the influence he had in his heyday.”